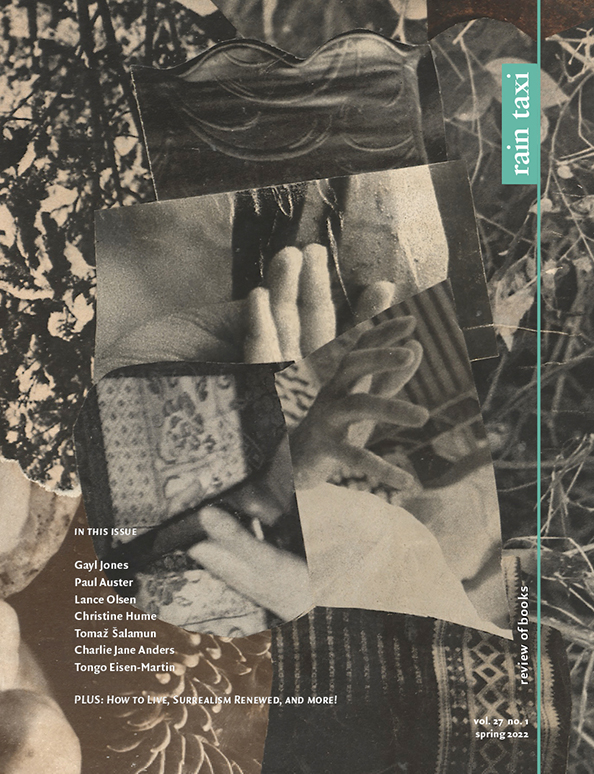

Volume 27, Number 1, Spring 2022 (#105)

To purchase issue #105 using Paypal, click here.

INTERVIEWS

Taylor García: Writing Multiple Identities | interviewed by J. Saler Drees

Caitlin Hamilton Summie: The Ordinary and the Everday | interviewed by Eleanor J. Bader

Christopher Citro: Happy, Sad, Happy | interviewed by Christopher Carter Sanderson

FEATURES

How to Live: A Question That Won't Die

Rescuing Socrates | Roosevelt Montás

The Good Life Method | Meghan Sillivan & Paul Blaschko

Breakfast with Seneca | David Fideler

| review-essay by Scott F. Parker

The New Life | a comic by Gary Sullivan

PLUS:

FICTION REVIEWS

Palmares | Gayl Jones | by David Wiley

Skin Elegies | Lance Olsen | by James W. Fuerst

Narcisse On A Tightrope | Olivier Targowla | by Joseph Houlihan

The Dog of Tithwal | Saadat Hasan Manto | by Graziano Krätli

The Blue Book of Nebo | Manon Steffan Ros | by George Longenecker

The Turnout | Megan Abbott | by Erin Lewenauer

Failure to Thrive | Meghan Lamb | by Garin Cycholl

NONFICTION REVIEWS

Remade in America | Joanna Pawlik

Surrealist Sabotage and the War on Work | Abigail Susik | by Paul Buhle

Never Say You Can’t Survive: How to Get Through Hard Times by Making Up Stories | Charlie Jane Anders| by Stephanie Burt

Clairvoyant of the Small: The Life of Robert Walser | Susan Bernofsky| by Steve Matuszak

The Deeper the Roots: A Memoir of Hope and Home | Michael Tubbs | by Eleanor J. Bader

Saturation Project | Christine Hume | by Erik Noonan

Sorry Not Sorry | Alyssa Milano | by Nanaz Khosrowshahi

Making the Ordinary Extraordinary: My Seven Years in Occult Los Angeles with Manly Palmer Hall | Tamra Lucid | by Zack Kopp

POETRY REVIEWS

Shapeshifter | Alice Paalen Rahon | by John Bradley

Wonder Electric | Elizabeth Cohen | by Hilary Sideris

Blood on the Fog | Tongo Eisen-Martin | by Lee Rossi

The Enemy of My Enemy is Me | Conor Bracken | by Christian Bancroft

The Man Grave | Christopher Salerno | by Christopher Locke

Above the Bejeweled City | Jon Davis | by Greg Bem

Baby Axolotls Y Old Pochos | Josiah Luis Alderete | by Patrick James Dunagan

Star Things | Jess L. Parker | by Luanne Castle

Tomaz | Joshua Beckman & Tomaz Salamun | by John Bradley

COMICS REVIEWS

Himawari House | Harmony Becker | by Trisha Collopy

Ernst also ended up in New York City, marrying the heiress Peggy Guggenheim. Weisz Carrington includes here a group photo of expatriate artists. Ernst sits in the second row with his adult son Jimmy (from his first marriage) and Guggenheim standing behind him. Carrington sits on the ground in front of him to his left. Friedrich Kiesler, casually lounging beside her, stares at her rather than facing the camera like everyone else, while Stanley William Hayter sits on her other side with his face partially still turned towards hers, as if he had looked towards the camera just in time. Between the two men, Carrington stares intently forward, ever steadfast in her “refusal to be treated like a sexual object.” Notably, Guggenheim and photographer Berenice Abbot are the only other women in the photograph of fourteen “artists in exile.”

Ernst also ended up in New York City, marrying the heiress Peggy Guggenheim. Weisz Carrington includes here a group photo of expatriate artists. Ernst sits in the second row with his adult son Jimmy (from his first marriage) and Guggenheim standing behind him. Carrington sits on the ground in front of him to his left. Friedrich Kiesler, casually lounging beside her, stares at her rather than facing the camera like everyone else, while Stanley William Hayter sits on her other side with his face partially still turned towards hers, as if he had looked towards the camera just in time. Between the two men, Carrington stares intently forward, ever steadfast in her “refusal to be treated like a sexual object.” Notably, Guggenheim and photographer Berenice Abbot are the only other women in the photograph of fourteen “artists in exile.”

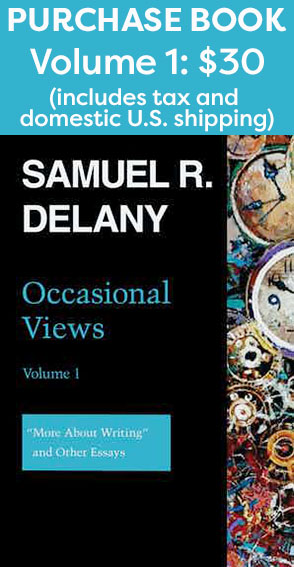

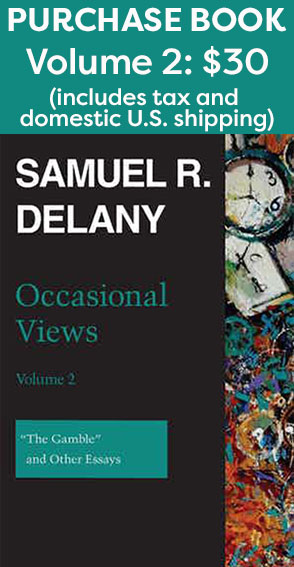

SAMUEL R. DELANY is the author of more than 40 books, including groundbreaking science fiction novels such as Dhalgren and Nova and the essential nonfiction study Times Square Red / Times Square Blue, recently released in a 20th anniversary edition. He has won four Nebula awards and two Hugo awards, as well as the Anisfield-Wolf Lifetime Achievement Award, among many other honors. Retired from years of teaching at the State University of New York, the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Temple University, he lives in Philadelphia.

SAMUEL R. DELANY is the author of more than 40 books, including groundbreaking science fiction novels such as Dhalgren and Nova and the essential nonfiction study Times Square Red / Times Square Blue, recently released in a 20th anniversary edition. He has won four Nebula awards and two Hugo awards, as well as the Anisfield-Wolf Lifetime Achievement Award, among many other honors. Retired from years of teaching at the State University of New York, the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Temple University, he lives in Philadelphia. LAVELLE PORTER is an Assistant Professor of English at New York City College of Technology, CUNY. He holds a B.A. in history from Morehouse College, and a Ph. D. in English from the CUNY Graduate Center. His writing has appeared in venues such as The New Inquiry, Poetry Foundation, JSTOR Daily, and Black Perspectives. He is the author of The Blackademic Life: Academic Fiction, Higher Education, and the Black Intellectual published by Northwestern University Press in 2019.

LAVELLE PORTER is an Assistant Professor of English at New York City College of Technology, CUNY. He holds a B.A. in history from Morehouse College, and a Ph. D. in English from the CUNY Graduate Center. His writing has appeared in venues such as The New Inquiry, Poetry Foundation, JSTOR Daily, and Black Perspectives. He is the author of The Blackademic Life: Academic Fiction, Higher Education, and the Black Intellectual published by Northwestern University Press in 2019.