Leslie Moore

Leslie Moore

Littoral Books ($18.95)

by Jefferson Navicky

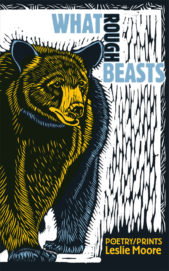

For those artists drawn to both the visual arts and poetry, there must come a moment when one wonders, what format now? How is this particular idea calling to be expressed in the world of tangible expression? This dilemma animates the central dichotomy of Leslie Moore’s book of poetry and prints, What Rough Beasts.

As an epigraph to What Rough Beasts, Moore offers an excerpt from Maxine Kumin’s poem “Nurture”: “Think of the language we two, same and not-same, / might have constructed from sign, / scratch, grimace, grunt, vowel: // Laughter our first noun, and our long verb howl.” Moore creates her own version of this language, a synthesis of word and art, word and animal. The first poem in the book, “Dichotomy,” begins, “I don’t have a poem today, but I’ve got the first blush / of color on two relief prints.” And so Moore is off and running with her theme of poem vs. print, and the energy that arises from this frisson:

Instead of putting one balky word after the other,

I’m in my studio, sharpening tools, carving

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . anticipating the denouement

when loose strands come together and my birds resolve,

without a word.

In this example, words are “balky,” and the creative flow necessary to work on a poem is far away. The speaker has deferred writing a poem in favor of working on relief prints. There’s a touch of feistiness at this choice, almost as if the speaker imagines defending the choice to a group tapping their fingers in expectation of a poem. Presumably in the moment there was only print as poem and the obvious relief, at the end of this poem, that the “birds resolve, without a word.” Birds, in this example, are more elegant than words, as they often are. But anyone who may be thinking that a book of poetry about birds wouldn’t be politically charged and relevant will be happily mistaken.

A tip of the cap must be given to Littoral Books and their designer Lori Harley. Moore’s prints jump off the page in rich, full color plates. So often images are relegated to the middle of a book where a few color plates require a reader to return to them again and again throughout the reading of the book. Not so with What Rough Beasts. A reader can nearly feel the texture of the prints with their fingers.

In closing, we must return to the animating dichotomy of the book, which arises in another poem, “On Presenting to My Poetry Group the Barn Owl Linocut I Finished This Week Instead of Writing a Poem.” Once again, the print is a stolen pleasure against the obligation of the poem. The poet hopes that the group will “admire / the structure of the print” and she imbues the print with the language of a poem: “They may feel a rhythm / in spilling pine, sense meter / in wingbeat, catch their breath / at the tonality of moonglow.” The poem doesn’t reveal if the group felt these sensations, but readers certainly will. The poem and print cascade down the page as one’s eye jumps back and forth from poem to adjoining image. It’s a very pleasurable rhythm indeed. It’s almost like flying.