Rain Taxi Peace Tee Member sale!

Only $15 including shipping in the U.S. Choose your cut and size below to purchase!

Only $15 including shipping in the U.S. Choose your cut and size below to purchase!

by Kevin Brown

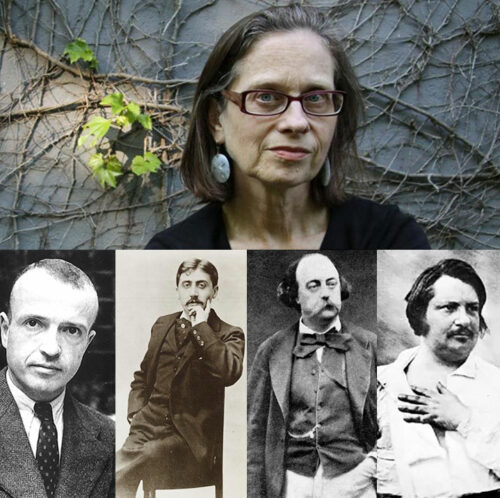

Five books by authors ranging from Balzac to Michel Leiris, three of them translated by Lydia Davis, can be used to understand centuries of French literature and history. One could argue that not only Michel Leiris, but Marcel Proust, Gustave Flaubert, Honoré de Balzac, and ultimately Davis herself, are all quasi-ethnographers possessed of a grasp of both how society works and a sufficient distance to view it objectively. They are able to then write about it from both on high (le monde) and down low (le demi-monde) yet stand at a sufficient remove to retain what translator Raymond N. MacKenzie calls “a clear-sightedness that is almost but not quite cynicism.” This essay examines the evolution of this insight into French culture through some of literature’s most gifted contributors.

One of several Leiris titles Davis translated over thirty years, Brisées: Broken Branches (Northpoint Press) is a gathering of art catalogue essays, reviews, letters to the editor, meditations on the body human and politic, and other occasional personal pieces. Brisées connects to the musculature of Leiris’s overall body of work the way Swann’s Way, Madame Bovary, Lost Illusions, and Lost Souls connect to the skeletal system of French literature. In his 2020 New Yorker article on Leiris, Sasha Frere-Jones notes there are books that “are fully intelligible only as part of the project of a life.” Brisées, like Davis’s Essays, is among them. The groundwork Davis laid translating Leiris’s essays prepared her for what might seem the “pinnacle” of her career as translator—rendering Proust—but counter-intuitive as it may sound, Davis says “the less popular Leiris,” not Proust, may in fact be, “stylistically more intricate and daunting.”

There’s a rational explanation. Like Proust, Leiris is saddled with an “unshakeable and undeserved reputation” for being difficult. During the drafting of his account of an expedition from Dakar to Djibouti (translated by Brent Hayes Edwards as Phantom Africa, Seagull Books, 2019) and thereafter, Leiris developed his books using the old index-card system, jotting down aches and pains, bits of fact, memories, dreams, reflections, lines of lineated verse, prose-poetry, and other scraps. Leiris’s “Cartesian Self” wrote by what he called “fits and starts and without regard for spatial or temporal unities.” To put it surrealistically, they’re like hypnagogic journal-entries, as if painted by Yves Tanguy, a poésie brut documenting the chiaroscuro of the unconscious “in the full light of midday.” Some of Leiris’s essays are as short as one paragraph, a page or two, leaning heavily on metaphor rather than exposition or argument. They sometimes communicate “by way of allusion, analogy, evoking an image.” Davis’s description of Rimbaud’s prose can also be said of Leiris: “A wealth of images . . . develops by leaps of immediate personal association rather than by sequential or narrative logic.”

Leiris excels at physical description. He watches writers, painters, composers like Erik Satie, Joan Miró, and Aimée Césaire. Giacometti’s drawings, engravings, etchings, paintings, and sculptures inspire some of Leiris’s most distinctive writing. And part of what makes Davis such a good translator is disappearing into her role, or seeming to. Adhering to the French tradition of “clear and exact prose,” Davis articulates Leiris’s ideas in such a way that they seldom seem “unnecessarily abstract and obtuse.” Such transparency means the reader isn’t peering over Davis’s shoulder as she translates Leiris, or peering over Leiris’s shoulder as he writes about Giacometti; the reader is standing alongside Giacometti himself, with his “crown of wooly hair,” as he agonizes—merde!—over a figure-study of “isolation and inertia,” the pinched-clay pockmarks and bored-in eyes of a miniature head perched atop “sad stylites.”

Leiris came to manhood as Proust was dying. It’s as true of Leiris’s essays as it is of Proust’s fiction that both are best understood in terms of deep thinking rather than mere phraseology. What Leiris calls “the Proustian illumination,” a certain train of thought, can only be elucidated during unavoidably long hours of concentrated drafting. Leiris is sometimes saying not very novel things but in utterly novel ways. Once you’ve read himon authors such as Paul Eluard, the poet of love in time of war, whose Letters to Gala (published in Jesse Browner’s translation by Paragon House, 1989) is a firsthand account of the Surrealist movement, for example, or pivotal 19th-century predecessors like Rimbaud, who influenced that movement—it becomes clear Leiris is, like Proust, a demanding but not especially “difficult” writer.

The Leirisian sentence, tied in stubborn knots of clause and subclause, reflects contradictions in the man himself. On meeting him, Davis thought Leiris compartmentalized, which seems mirrored in his prose. His person, shesays, was “tailored, spotless.” From getting on the number 63 bus near his apartment to getting off near the gardens of the Trocadéro, Leiris smokes a cigarette and trumpets into his handkerchief, lost in the fugue-state of his own thought, past the point where “a mode of shared understanding” can follow “our private meditations.”

Every author, says Leiris, is “the historiographer of his own themes.” His training as an ethnographer placed Leiris in the perhaps impossible “position of impartial observer, detached from the system of values [one] inherits from [one’s] own culture and likewise detached from the cultures [one] studies.” Ethnography allowed him to form “a concrete view of . . . the social minimum that defines the human condition.” But it washis taste for poetry that led Leiris to ethnography, not the other way around. The self-begetting essays in Brisées range from a lecture on Haitian voodoo priests to prose-arias of minotauromachy before coming back to ethnographic contributions to French journals on the syncretism between African spirits and Catholic saints. Davis says “Leiris’s project was to take himself as subject, with a sort of ethnographic objectivity, and write himself into being, to arrive at a sense of himself and how best to conduct his life, through the years-long, intensive labor of exploring himself through writing.”

Readers shouldn’t expect Brisées to wind itself seamlessly around a central theme. The “Ariadne thread” tying these essays together is Leiris’s effort to follow the many aspects of art as one whole—the circus clowns of Picasso’s Rose Period, dance, music, theater—in order to “arrive at a complete view of man encompassing his twofold existence as a product of culture and a fragment of nature.”

Proust was about thirty when Leiris was born; by 1909, he’d arrived at the mature style we now call “Proustian.” Swann’s Way (Penguin Classics, $20) tells two related yet distinct stories: one involving Marcel, a younger version of our Narrator, the other about Charles Swann, a friend of Marcel’s family. “Swann in Love,” the psychobiography of jealous obsession embedded within, is a novella of manners flashing back to a period 15 years before the narrator was born and continuing through Marcel’s youth at Combray, where his grandparents live and his family visits during holiday vacations. Taxiing down the runway for the first 195 pages, the novel sprouts wings and generates lift, a magic-trick exhilarating to witness. A reader who gets that far may find the rest hard to put down.

Swann’s Way is less daunting when its many modalities and disquisitions—adage, aphorism, apothegm, architecture, art criticism, literary criticism, maxim, music, natural history, portraiture, prose poem, proverb, theater—are thought of as essays in search of a novel. Some have questioned whether in order to achieve hybridity, Proust sacrificed achieving “unity, life.” Whether describing a waterlily, a cathedral façade or the racing of his insomniac thoughts, there’s something of what Davis in another context calls “deliberate overload”—auditory, gustatory-olfactory, tactile, visual—in Proust’s perceptions. Sasha Frere-Jones wrote that, “Leiris doesn’t interpret [a thing] so much as study himself in its presence,” and it’s Leiris who’s most helpful in this context because precisely the same can be said of Proust. “Every observation,” Leiris writes, “is a relationship between someone looking and something looked at.” Oftentimes Proust’s Narrator, insisting that the reader “pay attention to me . . . know me!” is pushing the limits of the communicable past the point of the ineffable. Leiris is making what he calls “a perpetual encroachment of the act of narration on the thing narrated.” Proust doesn’t just toe the line between the all-consuming “I” and the universal “we,” between absorption and self-absorption, between direct or indirect object and almost overwhelming subjectivity, between pitiless scrutiny and self-pity—he crosses it. Proust isn’t so much a “difficult” as an experimental writer, attempting to write as Monet painted or Wagner composed. It’s in the nature of experiments to test failure.

Swann’s Way is full of eccentrics such as Proust. “Like certain novelists,” he “has divided his personality between . . . characters.” Proust is not always Marcel, or vice versa. Asthmatic, noise-sensitive, Marcel has much in common with our Narrator, whom Proust calls “the unconscious author of my sufferings,” but is not necessarily the same person. Likewise, “I began to take an interest in [Swann’s] character,” our Narrator says, “because of the resemblances it offered to my own.” Swann’s eczema, his balding red hair, and patchy beard in no way resemble the features of our androgynous pretty-boy with curl papers in his hair. On the other hand, Swann, “my other self,” is very much like Marcel in that he’s “a shrewd observer of manners.” Marcel’s “studious youth” recalls “the inspirations of [Swann’s] youth, which had been dissipated by a frivolous life.”

Haunted by unfinished works like The Human Comedy, by unrealized talents like that of Swann, Marcel decides to become a writer, to describe faithfully what he sees in nature, art, and society. One day, Marcel dreams, “I would be the foremost writer of the day.” A man of 38 subsisting on croissants and caffeine, Proust spent the last dozen years of his life in search of lost time, reliving it from childhood to his present twilight moment in European civilization. Sometimes in the guise of Marcel, sometimes as Proust himself, our Narrator is writing himself into being.

Passages in Proust are sometimes long, and if it’s been decades since you last read a couple volumes from In Search of, it can take some time to readjust because within “his long sentences, far-fetched comparisons, and over exuberant eloquence,” sometimes very little actually happens. But Proust’s sentences don’t ramble; they are built on solid foundations of syntax and grammar. Whatever problems readers may have with him, mere length shouldn’t be among them. Proust’s storytelling breathes, sometimes shallow and gasping, sometimes deep. But he can be strikingly succinct, and to her credit as translator, Davis can match him for brevity or expansiveness: "He raised himself on his tiptoes. He knocked.”

The “Proustian sentence” isn’t one thing; it’s many things. You might even say, stretching the comparison to absurd lengths, that the Proustian paragraph itself is not a single thing, continuous and indivisible. It is composed of a molecular infinitude of successive sentences, of different sentences, which may in themselves seem ephemera, but by their interrupted multitude give the impression of continuity, the illusion of unity.

That said, a single sentence of Proust’s can go on for an entire paragraph, and that paragraph for several pages sparsely populated with commas unless the author is striving for effect, in which case he may sometimes flat or sharp them like “wrong notes coaxed by unskillful fingers from an out-of-tune piano.” Dialogue is sometimes broken out conventionally, as in a stage play, which permits those pages to go quite quickly. Other times, the dialogue stays within the paragraph. Chapter headings or section breaks are almost non-existent, in contrast to Flaubert or Balzac. This slosh-over effect forbids the reader to put the novel down and conveniently pick up the thread again. The thousand-odd pages of Within a Budding Grove and Swann’s Way, so needful of constant attention, are best suited to uninterrupted stretches of reading on a delivery device other than a smart phone. A reader has two choices: either indulge Proust as he introduces all the characters who will occur, develop, and recur throughout this seven-movement opus, as he introduces all the themes that rhyme with what’s gone before and what’s yet to come; or read something else.

Of course, Proust has his critics, and his critics have a point. Even Davis admits, in a 2006 letter to the editors of the New York Review of Books, that he can be “oppressively overwrought, even saccharine.” Some readers couldn’t care less about the gaffes Marcel commits or about his perhaps excessive disillusionment over the petty snubs of petty snobs who never really deserved all that flattery and fawning he’d lavished on them in the first place. And for some critics, Proust’s vast intellect and powers of observation seem squandered in this “study of the nobility; a Parisian novel; an essay on Sainte-Beuve and Flaubert; an essay on women; and an essay on pederasty.”

Proust’s Narrator shifts back and forth between the necessarily circumscribed “I” of Marcel, the third person “he,” she,” and “they” of “Swann in Love,” and the all-seeing eye of Proust himself and his philosophically generalizing “we” and “our” used in speculative digressions. The points of view get blurred, intentionally or otherwise. It’s hard to tell how and what one character, including Marcel, knew about another, and when that character knew it. Through what he called “retrospective illuminations,” Proust gives his Narrator access to information other characters lack. But the reader also begins to suspect things about Proust that he himself may not have known or wanted known. “Since I wanted to be a writer someday,” our Narrator writes, “it was time to find out what I meant to write.” Even Proust at his death could not have known how self-fulfilling this prophecy would be.

Unless he was gathering material for his great work of recapturing the past, Proust made himself scarce. Perhaps he realized literary genius would never have taken him “very far in society” anyhow. By the time of these reflections, Proust—a shut-in, mostly bed-ridden, like his great-aunt Léonie—mostly came out at night, his complexion ashen and his eyes hollowed out like a Giacometti portrait in monochrome. Even indoors, dining at the Ritz, Proust wore a heavy fur coat over his evening clothes, and evening clothes over his long-johns, refusing to remove his top-hat for fear of worsening his cold, his canals infected by the earplugs he always wore to drown out the neighbors’ noise. “How frightfully ill he’s looking,” people whisper, scandalized.

Proust wasted away to 100 pounds, and was dead, like Balzac, by age fifty-one.

What’s left to say about Madame Bovary (Penguin Classics, $17)? This novelspeaks to Proust’s notion that “the ideal is inaccessible and happiness mediocre.” In order to organize discussion surrounding this much-discussed work, let’s break this section down by act.

— Act One —

We first encounter Emma “in the freshness of her beauty, before the defilement of marriage and the disillusionment of adultery.” One obvious difference between Proust and Flaubert is their respective degrees of authorial intervention. Always intrusive, sometimes hectoring, full of digressions “thickened by a great mass of fustian,” Balzac addresses his reader directly. Meanwhile, Proust’s first-person Narrator passes moral judgments Flaubert’s omniscience does not allow. Flaubert is superb at asynchronous revelation of motive, how characters see one another, and how those same characters see themselves. From a vantage point whose spherical center is everywhere, its circumference nowhere, Flaubert hints by indirection at things the reader’s already beginning to suspect; he shows simultaneously the lies people tell each other, and the half-truths they keep from themselves.

Père Rouault, Emma’s father, offers Charles Bovary the consolations of philosophy to help him get over the grief he feels when his first wife dies. Before either the prospective bride or groom see it coming, cunning meets guilelessness as Rouault calculates how to dower Emma off to Charles, the way a farmer might auction off a less-than-prize heifer to a witless buyer. (Flaubert describes her teeth, as if she were a fine specimen trotted out among dung at a county fair, not just as “pearly” but “nacreous.” The old master practically railroads poor Bovary into the marriage arrangement.

By the morning after the big wedding day, Emma’s already fallen out of love with the reality of a marriage she feels martyred to. She’s married a physician with more than a little Norman peasant in him—he gargles his soup. While Charles is performing his country doctor duties, Emma—with too much time on her hands—passes her days thinking up extravagant names “for a perfectly simple dish that the servant had spoiled.” Emma and Charles: so close in the same bed, so far apart in the same room.

Meanwhile “one day nosed along on the heels of the next.” In Flaubert, as in Proust and Leiris, there’s maximalist “profusion within a frame” of description, as Davis puts it in "The Impetus Was Delight" from Essays One: the touch of a warm wind; the dogs’ volley-barking; white billiard balls caroming over green felt tables; that barnyard smell of a hen laying an egg. Vast amounts of data never seem to retard the narrative momentum of Bovary, however, because Flaubert horsewhips his narrative, foaming and frothing like a thoroughbred. At 350 pages, this booknever once feels drawn out.

Charles falls hard for Emma, as Swann does Odette, but Emma simply cannot “convince herself that the calm life she was living was the happiness of which she had dreamed.” Bored with him, Emma’s already contemplating adultery—though she never seems to admit that to herself. The reader never questions whether she’s going to cheat on Charles, only when and where. It’s a village, for Chrissakes! “Provincial life,” Balzac informs, “is based on a meticulous, detailed system of espionage, insisting that one’s private life be open to everyone’s view at all times.” How’s she supposed to pull off all this mounting and dismounting? And with whom?

— Act Two —

Flaubert’s timing and comic effects sometimes “stupefy the understanding.” One of Davis’s many achievements in translating Bovary is laughter on almost every page. And this is not accidental. She has clearly thought, very carefully, about keeping Flaubert funny. Any translator can tell you that carrying humor over from the source to the “target language” is one of the hardest things to do. Even when Flaubert is drawing your attention elsewhere, you find it impossible to ignore how marvelously well he’s doing it. The pecking orders of cruelty in many of these novels is similar and recognizable. In Proust, Françoise heaps verbal abuse on a Combray servant-girl whom Swann may or may not have impregnated while she is in labor pains; Forcheville tongue-lashes Saniette in front of everybody; Mme. Verdurin humiliates Swann in front of Odette and Forcheville. In Flaubert, the help bully farm animals; masters lord it over the help. Pompous pharmacist Homais is as abusive toward underlings he berates for their “ineducable incompetence,” as Proust calls it, as he is “drawn to those in Power.”

Emma’s disappointment breeds contempt. When Bovary undresses, she complains of a headache. Little by little, she refuses to share the marriage bed at all.

During this petulant depression, everything irks her, not least herself. A creature of moods and whims—now feverish with gaiety, now “drunk with sadness,” now aloof, now explosive with lust—Emma’s a bundle of misdirected energy. She stays up all night reading dirty books and sleeps till four in the afternoon, or else she’s compulsively neat, thrifty as a Picard village housewife, exaggeratedly attentive to her household duties and newborn daughter. Other times she literally can’t be bothered with the drooler. Her pathology sounds vaguely familiar. Leiris, too, suffered from bouts of clinical depression. Within months, Emma’s water-faucet tears, her “exaggerated speeches [concealing] commonplace affections,” are becoming tedious. Even before he’s conquered Emma, Rodolphe’s already plotting how to get rid of her. Boulanger dallies with Emma, smacking her emotions around like a tomcat toying with a half-dead mouse.

Flaubert shares with Proust an attention to detail verging on mania—especially in women’s fashion, for which Emma yearns as lustily as does Odette. For one who inveighs so mightily against the bourgeousie, the Old Rouennais has a gluttonously keen eye for material possessions. Emma lavishes on her much wealthier lover extravagant gifts she can’t possibly afford. She lies, cheats, Ponzi-schemes, goes on shopping sprees. But instead of gratifying, these presents embarrass Rodolphe.

Rodolphe writes Emma a florid letter. Reading it, Emma sprouts three gray hairs and faints dead away, lapsing into a coma; she remains bedridden 43 days. Once awake again, she begins contemplating suicide—an act Leiris attempted via barbiturate overdose. The blue jar on the third shelf in the capharnaum, once mentioned in Act Two, must be emptied by the end of Act Three.

— Act Three —

For Léon, Emma’s final lover, part of her charm as mistress is precisely that she’s a married woman, whereas she herself “was rediscovering in adultery all the platitudes of marriage.” They tire of each other.

After 240 pages, everybody in Yonville knows about Emma’s infidelities except Charles. Even when he finds in the attic a faded love letter to Emma from Rodolphe, Charles convinces himself their “love” must have been platonic. There are many plausible alternate endings. More than one character spells out for her the option obvious in the reader’s mind, a theme common to all four novels under discussion here. But in her own eyes, Emma is much too storybook a heroine for that: “I’m to be pitied, but I’m not for sale!” “Facts,” says Proust, “do not find their way into the world in which our beliefs reside.”

If readers in the monoglot “anglosphere” struggle through Proust and Flaubert, where to begin with Balzac’s vast fictional chronicle of France between 1815–1848, The Human Comedy? Two novels recently translated by Raymond N. MacKenzie, Lost Illusions and Lost Souls (University of Minnesota Press, $19.95 each), suggest an answer. Are these 1,066 pages worth the trouble? Unequivocally. To read Balzac, you have to accept him for what he is: a very uneven writer.

Langston Hughes, who might have bussed Leiris’s cabaret table without either knowing, is a recognizably Balzacian “type.” Wealth, like an estranged parent’s withheld affection, shunned Hughes all his life. He churned out plays, opera and oratorio libretti, literary fiction, and newspaper columns under his own name and pulp fiction under pseudonyms. He hustled from book contract to book contract, staying afloat on advances for books not even started much less finished, dodging landlords when the rent was due. The fictional version of this type, recurring in both Lost Illusions and Lost Souls, is poet-dandy Lucien Chardon de Rubempré. A young man from the provinces, he arrived with “the boldness of the social climber,” writes Balzac, and “came to the house [the Faubourg-Saint-Germain] five days out of the week, gracefully swallowed insults from the resentful, tolerated impertinent glares, and made witty responses to mockery.” Lost Illusions, the prequel to Lost Souls, is what MacKenzie calls “the truly foundational text in the vast Comédie, both in its form and its themes,” and might easily have been subtitled “Scenes from Literary Life.”

In some respects, literary life in 1822, the dawn of print media’s ascendancy, seems unchanged from that of our print media twilight in 2022. Media moguls still rely on interns performing “a year’s work for no salary.” What has changed is that the supply of journalists now far exceeds the demand for column inches. Lucien spends his days at the Sainte-Geneviève public library, where it’s drier and better lit than in his unheated garret, working on his first novel and his chapbook. Lucien gets a behind-the-scenes view of how publications are run; how gatekeepers see to it The Paper isn’t overrun by unsolicited contributors. “If you don’t already have a reputation,” one publisher, admiring his own manicure, frankly admits, “I’m not interested.”

Not content to live on bread and milk, Lucien networks. He becomes a theater critic and book reviewer—a “paid assassin” as Balzac puts it, “of literary reputations.” All he need do to get invited to dinner seven nights a week, for actresses to twine themselves around him like a clematis, to become an influencer in France and find a publisher for his own books, is to write witty reviews of other books he may or may not even bother to read, to “attack when [someone] says ‘Attack!’ and praise when [someone] says ‘Praise!’” Lucien’s first theater review is a success. He awakes to find himself famous, flattered, cajoled. Lucien “listened to all their nonsense,” Balzac winks, “and it impressed him, completing his corruption.” Now that he’s a journalist, with a mistress to boot, Lucien gives himself Byronic airs, “staring down the dandies who had mortified him.” “The looks exchanged,” Balzac writes, “were loaded like pistols.”

The problem isn’t that Lucien wants more—his own horse and carriage, a liveried coachman, beautiful surroundings to write in. The problem is that he wastes more time and energy schmoozing at editorial meetings than Swann fritters away at Verdurin soirées. Whereas Balzac, when not gathering material for his stories, was often “unable to come; he was finishing his book.” Lucien’s “as apt to end up hanged,” Balzac prophesizes, “as to make his fortune.” Our poet is doomed, but it takes him two novels to figure that out.

It was trendy in the 1970s to talk about György Lukács, social realism, and Balzac. What strikes a 21st-century reader about those takedowns of Lost Illusions or shakedowns of Lost Souls is their make-believe theatricality. At first, Balzac wrote Gothic potboilers under a pseudonym. These apprentice works had as few readers during the 1820s as his mature works in English probably have now. The odds against winning the genre-fiction lottery are long. Balzac should have known better. But he wagered anyway. Our great man from the provinces gambled and lost money he never lived to repay on failed schemes like politics and the printing business. He resolved to write under his own name the post-Napoleonic era novels we now know him for.

Salon readings, not newspaper serialization, were the way authors like Dumas, Hugo, Lamartine, Musset, and Sand were made known to a wider public. Balzac signed a contract in 1835 for Lost Souls, then tentatively titled “Scenes from Provincial Life.” His deadline was 1836. Working to dash off in twenty days a book that had been gestating in his mind for twelve years, at one point writing feverishly for three days straight, Balzac collapsed from exhaustion. He refocused in November 1836, and finished the project on January 20, 1837. The book went on sale that February and was serialized in French daily newspapers between 1837 and 1843, never on deadline and always over word-count by a writer juggling too many projects on too little sleep. Lost Illusions often bows in the direction of commercial elements that don’t always serve the psychological novel’s High Seriousness.

The University of Minnesota Press editions, usefully footnoted, are clearly intended for classroom use. But Balzac wrote not just for remote posterity, but to escape poverty in the here and now. His works have hot tears of Ivanhoe historical romance vying with dueling pistols at twenty-five paces; they put picaresque lives side by side with twelve-page letters of the epistolary novel that has “love as its subject and musk as its scent, sprinkled with madrigals and metaphors,” which letters are written in feverish haste and purposefully mislaid. Nucingen, the love-sick baron, goes running all over, searching for Esther the way Swann searches for Odette, who cheats on Charles the way Emma cheats on Bovary. Intimate scenes painted on a vast canvas constitute the Novel of Everything.

The world of Lost Souls is “amoral, hypocritical, brazen, dishonest, and murderous.” Much has been made of Balzac’s influence on espionage and crime fiction writers like John le Carré, Dashiell Hammett, and George Simenon. A hundred years after Balzac, writing Casino Royale, Ian Fleming was still complaining that genre fiction in general and spy thrillers in particular were too long, too poorly written, and bullet-riddled with clichés. Maltese Falcon seems almost Flaubertian in comparison. There’s an unavoidable trade-off in character-development for all those scenic locations and all that fast-cut/slow-mo action.

Lost Illusions, at 585 pages, is almost twice as long as Bovary. In places, it feels twice as drawn out. Flaubert admired Balzac despite “the stigma of aesthetic inferiority” Milan Kundera says he labors under. A careful student of Balzac, Proust admits that the Comedy, “magnificently overloaded” with proper names, is hard to track. Literally thousands of characters occur and recur in nearly 100 interconnected short-stories, novellas, and novels. Sometimes these “characters” are just names (“Albertine,” “Proust,” or “Marcel”) you can’t match a face to. There are 273 names in Lost Souls alone, many of them recurrences from previous volumes of the Comedy. Following the money, as Flaubert does, is what readers expect Balzac to do. In both Flaubert and Balzac there are particularized ledger accounts of how much everything costs. Even Proust, a trust-fund writer one might expect to be above such matters, we get a detailed accounting of how Odette’s willingness to have Swann to bail her out of money troubles bonds them together.

It would be better to skip Balzac altogether than to read him as hurriedly as he himself wrote. To a first-time reader I would give this advice: Go to bed early, get lots of sleep, get caffeinated, then machete your way through these thickets of longueurs. The reader who perseveres past the bad puns and maudlin bits will be rewarded, even as their patience is tried. The European federation seemed a wild dream in 1830. When Proust died in 1922, the 19th century we think we know—an era when nobody ate dinner till 10 p.m., servants prepared five-hour luncheons for thirty guests and forty candelabras, and the Bourse didn’t open trading till 3 p.m.—was an era when even Faubourg townhouses didn’t have electricity. One reason Balzac’s depiction of literary life remains so vivid is because that life was his life. Balzac didn’t invent bohemia; he frequented the stalls of used-book vendors along the quays from the Pont Notre-Dame to the Pont Royal, where starving writers like Lucien read books they couldn’t afford to buy. It’s hard to think of a more accurate depiction of it.

Balzac was a storyteller, MacKenzie writes, but much more than that. Balzac’s Comedy was envisioned as “a vast summa.” MacKenzie writes:

Whole family stories emerge across all these works, and the history, politics, and social relations of France are explored and analyzed from what seems like an endless series of varying angles. And allowing the reader to see these numerous characters from different perspectives, sometimes in the background, sometimes in the foreground, and in different situations at different points in their lives, gives them a depth that is unrivaled in fiction.

Peter Brooks thinks Lost Illusions is perhaps Balzac’s greatest novel. MacKenzie calls Lost Souls “one of the most energetic, compulsively readable works in all Balzac’s canon.”

Balzac’s insights into the cultural, economic, political, and social upheavals experienced by a fictional poet in his twenties—the Revolution, the Directorate, the Empire, the Restoration—as seen from the point of view of a novelist in his forties still seem relevant nearly 225 years after his birth. If “the true aim of [great] works is to stimulate ample discussion,” then the great man from the provinces, despite his flaws, is truly great.

French-language writers form a distinct subculture because “culture,” according to Leiris, “defined as the sum of the modes of acting and thinking, all to some degree traditional, peculiar to a more or less complex and more or less extended human group—is inseparable from history.” Leiris at 100 nods to Proust; Proust at 150 nods to Flaubert; and Flaubert at 200 nods to Balzac, born between the six months separating the collapse of the Revolution and 18 Brumaire, Republican Year VII of the French calendar. Each isa chronicler of French society both high (le monde) and low (le demi-monde), a spectator to what Balzac calls the “Theater of National Absurdity” who saw through what Leiris calls “the insanity of the current order of our social relations.”

One’s admiration is unequally divided, to paraphrase Swann, among the four. Leiris’s darkly surrealistic vision of human bodily functions as “organs of excretion” or, by metaphorical extension, of the body politic, of civilization itself, as a city “poisoned by a million sewers” is a vision Balzac would have understood. Lost Souls seems full of the 19th-century equivalent of 20th-century prisons like La Santé, an isosceles trapezoid in the heart of the hex, where the worst of the worst once clogged the eastern heart of the 14th arrondisement; and the capital itself sometimes seems a vast, plein-air penitentiary. Lost Illusions is a story of an idealistic young writer’s swift corruption. Proust’s ambition as novelist was “a desire to write a book that would rival Balzac’s panorama of Parisian society” and to frame within that frame the intimate history of a young man’s artistic and spiritual evolution. Satire in Bovary takes down many targets—windbag politicos, idiotic savants, mock-editorial columnists—with a quiver of energies that seems more sustained than that of the other three novels. Yet Balzac would have been Balzac with or without Flaubert and Proust. Could either Flaubert or Proust have realized himself without Balzac?

What’s the point of arguing whether Davis’s or some other’s translation of Bovary or Proust is “definitive?” There’d been 20 previous translations of Bovary into English alone. Hers is unlikely to be the last. MacKenzie says, “times change, idioms change, audiences change, and so does our sense of what sounds dated and what sounds right, what sounds bookish and what sounds vital.” Davis spent three years translating Bovary, “a complicated mechanism” it took Flaubert four and a half to write. Whatever the durability of her translations, their conscientiousness is beyond question. She puzzled for three decades over just three lines from poet Anselm Hollo. Readers can trust Davis to have erred, when she does err, on the side of what Peter Brooks calls “rigor and exactitude.” From each generation a reading of the classics according to its interpretive ability; to each generation a translation according to its needs.

MacKenzie warns readers in search of overarching themes in Balzac to seek them only in terms of “a unity of tone, of sensibility, and of outlook rather than plot structure.” The same could be said of Davis’s Essays, perhaps best thought of as collected nonfictions. The thousand or so pages of Essays One (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $23) and Essays Two (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $35) consist of anthology pieces, book reviews of others’ translations, introductions and prefaces to her own book-length projects, lecture series, and seminar and workshop talks. They center around the literary arts, the art of translation, and the visual arts. Because so much has already been said by reviewers pro and con about her versions of Leiris, Proust, and Flaubert, the following remarks are limited to how Davis’s work as translator, as revealed in her collected Essays, has helped her growth as author in her own right.

Davis questions “why one artist will evolve and change within relatively narrow limits while another will move from one expressive form to another.” Apart from her studies with Grace Paley, Davis isn’t a product of writers’ workshops. She’s not really an “academic,” although she teaches. Born as Michel Butor was graduating the Sorbonne, Davis studied German during primary school, Latin and Romance languages like Italian and Spanish later on. Many translators mentioned in her Essays are themselves canonic postwar writers born a generation before she was, or born, in the case of Elizabeth Hardwick, around the time Proust published Swann’s Way (1913). Some taught at institutions that shaped the thought of her generation but passed away around the time Davis’s earliest essays began pooling in her mind: Ralph Manheim on German-language and Eastern European writers like Peter Handke; William Weaver on Italian literature; Richard Wilbur on 17th-century French dramatists. In qualified retrospect, it seems a golden age of foreign language literature translated into English. By the time Richard Howard translated Mythologies (1972) and other works by Roland Barthes, or Gilles Deleuze’s Proust and Signs, or Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma, Davis had already lived in France. Her earliest essays date from the late ’70s and early ’80s, and reflect the influence of nouveau roman writers like Duras or Robbe-Grillet. By her late twenties, Davis was translating Blanchot.

The careers of Davis and Leiris intersect in many ways, the most obvious of which being that their essays complement their work in other genres. “Some of my work,” Davis admits, “comes right up to the line (if there is one) that separates a piece of prose from a poem, and even crosses it . . .” —something that is also true of Leiris. Visual artists inspire some of Davis’s most distinctive nonfiction in two radically different yet equally convincing essays. Color illustrations help one appreciate how faithfully Davis describes Alan Cote’s paintings without reading unnecessary “metaphorical signification” into them. “The Impetus Was Delight,” Davis’s essay on Joseph Cornell, strikes a balance between what she, the receptor, is seeing and what an auditor, the reader, is hearing. Even when you know the provenance of that essay is the multi-genre anthology A Convergence of Birds (edited by Jonathan Safran Foer and published by D.A.P., 2001), the question of whether the piece is fiction or nonfiction, non-lineated poetry or a prose poem seems moot. Hybridity being at the heart of what she is, Davis doesn’t really need a label. So why not call her a writer of “imaginative prose,” and leave it at that?

Davis does so many little things right most readers couldn’t or shouldn’t even notice. She takes pride in her own writing, but clearly wants these translations to last. Her submission to the text is such that Leiris in English does not sound like Proust or Flaubert. And each sounds very different from the Lydia Davis of Essays One and Two. At age 75, Lydia Davis has achieved something even more remarkable than a large and varied body of work: She has written herself into being.

Click links to purchase books discussed in this essay at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022

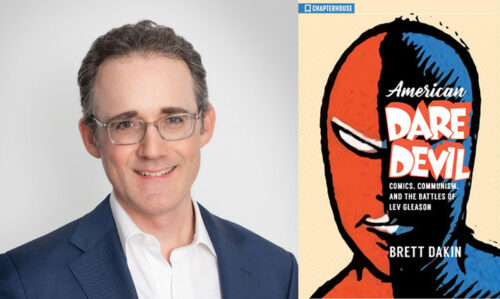

by William Corwin

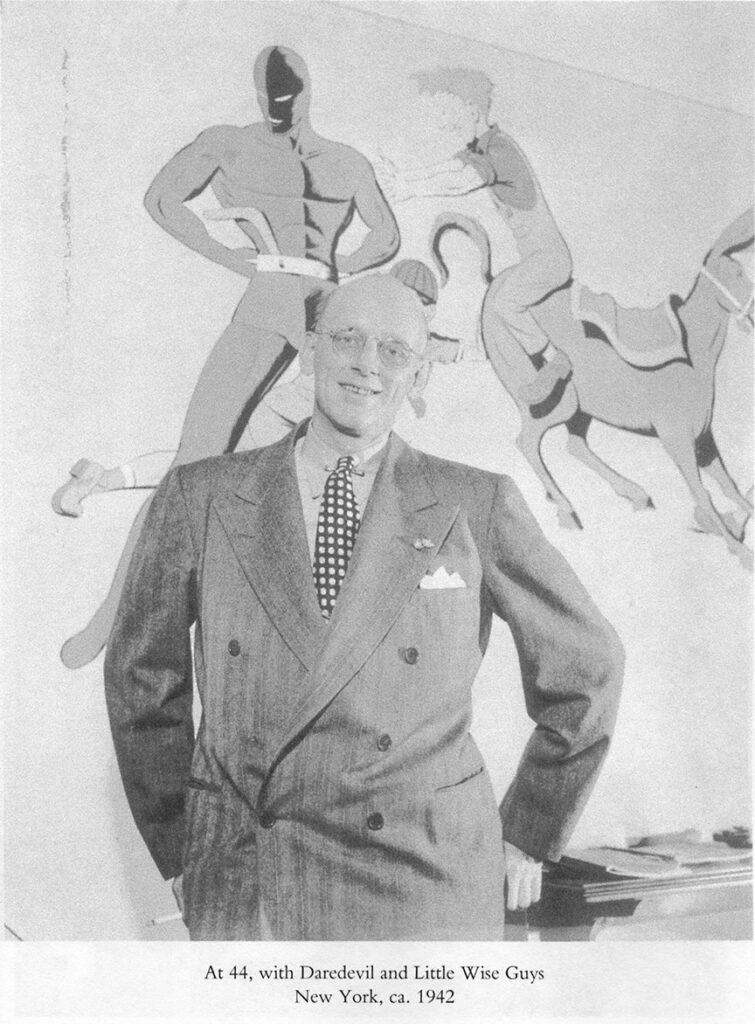

Brett Dakin‘s recently published Eisner Award-nominated biography, American Daredevil: Comics, Communism, and the Battles of Lev Gleason (Comic House, $24.99), tells the story of a real-life character who not only published over-the-top crime and superhero comic books during the industry’s “Golden Age,” but also spent weeks in front of the House Committee on Un-American Activities defending free speech. Dakin also delved into the more recent past in his 2003 book Another Quiet American: Stories of Life in Laos (Asia Books), and in our conversation below he unpacks the difficult task of presenting authentic narratives, transcripts, and dry research in a literary form. Some authors have found the solution is to write a fictional narrative to create some distance between subject and author, but Dakin—perhaps because of his legal background—has chosen non-fiction, which above all requires that the writer sit back and listen.

William Corwin: American Daredevil is a biography of Lev Gleason, your great uncle and a man who was active in many things, most notably as an early publisher of comic books. Your first book, Another Quiet American, was a memoir of your two years in Laos. Talk about the difference in your writing process between these two.

Brett Dakin: In the first book, the narrative was determined by things that happened, meaning the book is generally a retelling of the events in the order in which they occurred. In the second book, there were things that happened in the past, but the timing of my learning about those things was not necessarily consistent with the timeline of historical events. So I was faced with this choice. Should I write just a straight biography, i.e., “Uncle Lev was born on this date, and died on this date, and these things happened in between,” and remove myself from the narrative altogether? Or should I tell the story as I discovered it? What I ultimately ended up doing was a bit of both, which is to tell his story in a roughly chronological order, but also to give the reader a little insight into how I discovered pieces of information, because it wasn’t always that clean or neat a process.

WC: When was the moment you decided this person’s life would make a good book?

BD: I grew up hearing about Uncle Lev, but it never occurred to me to write about him, or even try to learn more about him. I heard stories from my mom, who was his niece, and he always struck me as a colorful character—I was taken with him, but from a child’s perspective, the same way that growing up I was taken with Drosselmeyer in the Nutcracker. I always thought, “Wouldn’t it be cool to have someone who swooped into town and showered all the children with gifts,” which is exactly what Uncle Lev would do with my mom and her friends when she was a child.

WC: More interestingly, there are also stories about Uncle Lev leaving the country and hiding, or ending up in prison . . .

BD: Yeah, well, those are not stories that my mom told me. The amazing thing that I ultimately learned was that in the community of comic book scholars, there was a lot of conjecture about where he went after things went south for his publishing business. But to get back to your question, I first started thinking about writing about Uncle Lev because I read Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (Random House, 2000). Kavalier and Clay is a fictionalized account, with completely made-up characters, but set in the very milieu that Uncle Lev not only lived and worked in, but helped create, because he was there at the birth of comic books in the 1930’s in Manhattan.

WC: And you communicated with Michael Chabon! Did he know about Uncle Lev? Had he heard of him?

BD: Absolutely, yeah. When I reached out to him, he was extremely excited to learn that someone was writing a book about Uncle Lev because he knew what a fascinating figure he was.

WC: How had Chabon found out about him?

BD: By reading—certainly my book is the first historical account dedicated to Uncle Lev, but he had appeared in histories of comic books in the past. So Chabon knew enough to realize that he was a fascinating figure. It was one of those moments when you see how fiction can spark an interest in history and that’s what it did for me, so I decided, let me figure out what Uncle Lev’s role in all of this was. The first thing I did was to go to the archives at Harvard University, because Harvard was where Uncle Lev went when he graduated from high school.

WC: Uncle Lev was sort of a litigious figure, and a litigated figure; one of the things that comes through in your book is that you elucidate many of these passages from documents from when, say, Uncle Lev was brought before the Committee on Un-American activities. Perhaps it’s a credit to your lawyer background, but you make this kind of writing and discussion interesting, these judicial verdicts and things like that. Was that something that drew you to the project—you said you had just graduated from law school, and you must have had an inkling that Uncle Lev had a lot of legal interactions.

BD: Again, to be honest, when I graduated from law school, I did not know that Uncle Lev had been so litigious and had been the subject of so many judicial and other inquiries, but I soon found out. But yes, that aspect of his life made me more excited because I’m a lawyer, and so reading court opinions, transcripts of hearings, of trials, of committee meetings, is something I enjoy—which I suppose can’t be said for everyone. What I tried to do in the book was take those proceedings, which can be rather dry in transcript form, and bring them to life on the page. I situate them in the context of what was going on in Lev’s life and in the comic book industry and the antifascist movement at the time. For me it was a natural fit—maybe given the fact that I went to law school and did the bulk of the research in the period right after I graduated and before I went to actually work at a law firm.

WC: In dealing with the accusations that were leveled against Lev, what mindset did it put you in to read those transcripts of conversations between, say, the FBI and your uncle? Did he seem frightened? Did they seem intimidating? Did you feel it was all political and smoke and mirrors? Very few of us have ever actually looked at FBI transcripts.

BD: One of the first things I did was I consulted the good-old-fashioned New York Times index, since at the time I was still in the frame of researching things by going to books with indices in them. I remember looking him up and being flabbergasted to find he was there. That solidified my thinking that there might be a book here, but one of the categories under which he was placed was “treason.” I was totally shocked by that. The reason was that he was accused of being a communist and categorized with people who were considered to be advocating the overthrow of the United States government. My feeling now is the same as it was then, which is that it was totally absurd—nothing could have been further from the truth in the sense of Uncle Lev’s view of the United States government, which was extremely positive. He was a strong believer in FDR and in the American democratic experiment; he served in World War One and in World War Two; he deeply loved his country, but also was deeply critical of it when he felt necessary, which is exactly the way I would categorize myself. So I was kind of shocked and a little bit disturbed to find that “treason” was the word that was associated with Uncle Lev at the beginning of my research.

The next part of the process was looking into it and seeing what their evidence was of that. And the fact is that the FBI—and I obtained his file—tracked him for more than a decade. I read through the entire file, along with reports of Uncle Lev in the U.S. army, in House Committees, in New York State Legislative committees. I mean he was investigated by all sorts of bodies for various reasons, and there was never any evidence to suggest that he supported the overthrow of the United States government. He lived a perfectly comfortable and happy life in the suburbs of New York for most of this period, commuting to Manhattan every day in a chauffeur-driven Packard; the idea that he would want the system that had been kind to him to collapse struck me as absurd from the outset. Now, on the other hand, it’s very clear that Uncle Lev was moved by the principles of the communist party in the United States, but his ultimate goal was to stamp out fascism, in Europe and in the United States. To him those threats were very real, and today we are seeing that those threats remain very real. He fought against it in his political activities and in his comic books.

WC: Let’s talk a little more about your method of writing: Do you take copious notes? In your previous book, Another Quiet American, there are stories of you teaching English to a General in Laos, going to rallies, and interacting with various characters—bureaucrats, expats, sometimes romantic involvements. As a writer in a foreign country, did you sit down at your desk every day, were you keeping a journal? And did you go into this experience thinking there was a potential for a narrative?

BD: I did. I went into the experience open to the possibility of writing about it in some form. I lived in Laos for two years; the first year there was less writing and more living. I didn’t keep a diary, but I definitely jotted down notes and thoughts as I went along. But the second year I began to write about my experience, so I would dedicate a portion of every day, usually at night when I was at home after being out and about in Vientiane, the capital. I would not just take notes but write in narrative form, stories of the people I’d met and the experiences I’d had. Those vignettes formed the basis for the manuscript that I put together after I had left the country and I spent a lot of time writing it when I was living in Vienna—from a remove I could see better how those stories could come together into a coherent narrative. By the time I moved back to the U.S., I had something I could shop around to publishers.

WC: When it was time to go through your notes, what was the process? Was there a sizeable amount of change in terms of writing or was it mostly just tidying things up and framing them, choosing which stories to tell?

BD: Well, first, there was a lot of cutting because I wrote about some things that upon further reflection were not that interesting, or that I didn’t think would be interesting to an audience other than me. A lot of prioritization went on, sifting through and drawing out the stories that might be most interesting to a general audience. Then another part of the process was taking stories and contextualizing them—situating them within the historical or societal context. If I were writing the story of a particular expat that I met, for example, I would really spend some time researching the relationship between the country that person was from and Laos. So that was a matter of fleshing out these stories so they weren’t just me saying what I did or heard but also backing it up with other sources or just situating the stories in a larger context, so the book would have value to someone who wanted to learn about Lao history and culture and society. Ultimately, I never viewed the book as a book about me. Obviously, I am the narrator and the main character, I suppose, because I’m always there, but I always viewed myself as a vehicle through which to tell other people’s stories.

WC: There’s a wide spectrum of literature involving an outsider coming to a country in the midst of upheaval. It can be enlightening, but also colonialist, so it’s a problematic body of literature, regardless of whether it’s self-critical or not. How did you address that in your book?

BD: Well, I try not to skirt the issue but write about it, to write about my struggles with my role as an American in a place that had been heavily bombed for years by the U.S. military—and bombed with, if not the explicit, then the tacit support of the American people. We were not fully informed about the so-called secret war in Laos, but had we been, would there have been an uproar such that the bombing of Laos and Cambodia would have come to an end sooner than it did? I’m not so sure. Frankly, it seems doubtful given what we know about public opinion regarding the war, which was always relatively strong until the very end of that long and horrific period in American history. So I try to write about my mixed feelings about being in the country and really try to listen more than talk, to suppress opinions that I might have and solicit other points of view instead, and I think that helped me to write better stories, because frankly I wasn’t a main driver of the things that happened to me while I was living there. I was allowing other people to drive the narrative; as the title hints at, Another Quiet American: Stories of Life in Laos isn’t really about me, it’s about the people that I met and their stories.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022

Jhilam Chattaraj

Hawakal Publishers ($12.99)

by Dhishna Pannikot

Jhilam Chattaraj’s Noise Cancellation offers poems that focus on the wake of Covid-19 and our correspondingly evolving lifestyles. Chattaraj’s poems are raw and the collection is intelligent, judiciously presenting the longer segments of “Active Noise Control” before heading towards the nano-poems of life in India in “Portraits in Pods” and culminating with “Noise Cancellation.”

Chattaraj’s poems provide glimpses from various states in India, including Kolkata and Hyderabad, and extend their scope to the Andaman Islands. The poems are intricately connected through descriptive aromas that lead the reader to “imagine a mustard afternoon” or bring in “a distilled escape from the tandoors, tarkas / the measured spoons of corporate dining.” Chattaraj often contextualizes the yearning for home via home cooking, “unheard by Apps and delivery boys.” Bengali and Hyderabadi cuisine has a large impact on Chattaraj’s writing, with a careful blend of spices and flavors coming through in “Aloo Posto,” “Phuchka,” and “Ugadi Pachadi.” The “mythic joy beyond noodles, / burgers and pizza” is depicted in “Phuchka,” where the poet turns readers towards the legacy of North Indian food.

The language in Chattaraj’s poems is also a blend of English and Bengali, and one can observe words like “kodai,” “baati,” “tarkas,” and so on taking root in the minds of readers. In the exquisite poem “Ugadi Pachadi,” the poet mentions that “marriage is like a raw mango; / a surprise turn of senses,” which evokes both the sense of taste and the newness of the nuptial experience, where

We harden into pepper corns,

fingers, furious, tap the soundless

heat of agitation.

Our voice breaks into salt;

white, grainy, afraid

of losing hair, wings and words.

Chattaraj also dwells on intimate feminine experiences through poems like “Sari,” “Block Prints,” and “Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird.” In “Sari,” she deftly uses metaphor to condense the experience of being a woman when she writes, “my mother’s sari is a scripture, / a flag carrying countries of household truths” and “there’s love and violence / that only the pleats of the sari can tell.”

From these continental poems, the poet then takes a turn towards the Andaman Islands in the poems “Ross Island” and “I Will Fall Sick if You Photograph Me,” presenting untouched nature as “a triumphant answer to ‘man’s search for man.’” There is also a connection to India’s colonial past that the author often brings to her poems, exemplified by the striking line “lonely British sentries amid the rich blooms of ‘aphim’ fields” in “Aloo Posto.” Chattaraj presents the raw reality of the present as well in “What T.S. Eliot Knew about the Pandemic”: “Noise without speech; food without taste. / Bruised breaths; death has undone so many.” In another poem she continues, “in the sea of newsprint, / poets dig dirges, / and share a drink or two with sanitized words. // . . . // Poets are writing, coughing and dying. / The final orchestra plays for them too.” The pandemic also brought changes in the sphere of academia, and the monotony of online teaching is well captured when she writes, “I became the sum of pixels and spreadsheets.” The title poem brings back how this time rooted us to the basic needs of life: “Dog-like, I wait // at the door of monks / for milk and hugs. // I learn to live mild. / Sit, eat, pray // for a change.”

Through this intense collection, Jhilam Chattaraj brings to light a blend of tradition and modernity, encouraging the reader to unplug a while and bask in Noise Cancellation.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022

Robin McLean

And Other Stories ($25.95)

by Garry Craig Powell

Exceptional books transcend the usual categories. Is Robin McLean’s Pity the Beast a modern-day western? Is it feminist? Is it postmodern? In fact it is all of these, and yet to pigeonhole it in such terms is reductive, and might, unfortunately, lead a reader to miss the complexity and richness of the novel.

The plot is almost traditional: A horrifying crime goes wrong, the victim survives and escapes, and a mounted posse sets off in pursuit, intent on finishing the job. The pitiless, graphic violence will inevitably remind some of Cormac McCarthy. But if you’re thinking Clint Eastwood movies, you’re wrong. Ruthless as the main men are, they are also educated. They philosophize, discuss Freud and Jung, and quote from Shakespeare and the Bible. One of them is gay.

These details represent surface-level departures from the conventional western, but the most meaningful difference is that the hero of Pity the Beast is a woman—although McLean is too deep and complex a writer to simply reverse the roles. While all the men in the novel commit evil deeds (with the exception of the deputy, a well-meaning greenhorn from New Jersey), perhaps the most evil character is not only a woman, but the victim’s own sister, Ella. And while Ginny, the protagonist, fights bravely, she has her own darker side too.

Postmodern in structure, Pity the Beast has several narrative strands; the main, realistic one deals with the pursuit of Ginny as she flees through the Mormoras (a fictional mountain range) towards Canada. McLean mixes in many other threads, however: the postcards written (but not sent) by the deputy to his neglectful mother; the fantasies of the Rodeo Kid, who sees himself as the hero of a Gunsmoke-style TV serial; a post-apocalyptic science fiction story about a female yeoman on a spaceship from another planet; and rational, articulate conversations between the mules in the posse’s train. The strategy of multiple plotlines always runs the risk of being labored and pretentious, and indeed, it’s not wholly successful here—the Rodeo Kid’s fantasies are not always consistent in voice, and at times the sci-fi story loses its focus and takes us too far away—but the purpose is clear. The author adds these additional narratives not to show off her cleverness, as so many writers do, but to imbue the main plot with resonance on a far grander, even a cosmic, scale.

Ultimately, this novel asks who human beings really are. The educated ranchers consider themselves deep and rational thinkers, refusing to acknowledge that they are also rapists and murderers, and—as we see in the post-climate catastrophe strand—they are blindly destroying the planet too. But the most successful of all the sub-narratives is the non-human one, that of the talking mules. It’s humorous and moving. How could one not feel compassion for the plight of such maltreated animals? Above all, it has the effect of eliding the distinction between beast and human. If beasts could talk, how different from their masters would they be? Not very much, the novel seems to imply.

The most outstanding feature of Pity the Beast, however, is the language. “Not since Faulkner have I read American prose so bristling with life and particularity,” J.M. Coetzee writes in a blurb. That’s a colossal claim, but it’s one the novel lives up to. No excerpts can do justice to the sheer richness and idiosyncrasy of the style, but in one particularly descriptive passage McLean writes, “His eyes, at least, worked miraculously well here. He saw jagged for the first time in his life, slick and mossy and huge and soaring.” Readers can also find some homespun philosophy in the book’s dialogue:

“All that’s pertinent is mixed together in the mountains,” Saul said. “Every appetite is natural. Must be. Arising as it does from a living natural being.”

“Vikings were buried at sea. The red-haired islands were solid rock.”

“Heat can cause insanity.”

“Lack of sleep.”

“The girls travelled west with the North American Indian trade.”

“Sea supremacy of Spanish galleons.”

“Books, braids, or booty.”

“Humans have strange drives.”

“Inscrutable inclinations.”

“Every appetite is natural,” Saul insisted.

“Even murder is natural, incest.”

“Must be.”

That’s the nub of it. This book is Hobbesian, bleak in vision, and if it’s not perfect, that’s because of its vast ambition. McLean is an important writer, one of the few who really matter at this precarious time in human history. She dares to think for herself, and to see things as they are, no matter how frightening that vision is.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022

With special guests Douglas Kearney, Miré Regulus, and Sayge Carroll

Wednesday, June 8, 7:00pm

Open Book, Target Performance Hall

1011 Washington Avenue South, Minneapolis

FREE in-person event! Proof of Covid-19 vaccination (or negative PCR test taken within the prior 72 hours) required for entry; mask wearing is strongly encouraged while in the performance hall.

Reception to follow, courtesy of Coffee House Press!

Join us as we celebrate the release of the deja vu: black dreams and black time (Coffee House Press) with an evening of performance and poetry by the amazing California-based writer Gabrielle Civil and a handful of her creative comrades from the Twin Cities! Emerging from the intersection of pandemic and uprising, the déjà vu activates forms both new and ancestral, drawing movement, speech, and lyric essay into a performance memoir that considers Haitian tourist paintings, dance rituals, race at the movies, Black feminist legacies, and more. With intimacy, humor, and verve, Gabrielle Civil blurs boundaries between memory, grief, and love; then, now, and the future. Don’t miss this!

"With this work, Gabrielle Civil continues to model generosity, bravery, and vulnerability as core principles of black feminist performance, creativity, and living. Read it for the beauty, the black feminist references. Read it for a particular herstory of this time. Look for what you might be unknowing right now and what you need urgently to remember.” —Alexis Pauline Gumbs

Can’t make it to the event? We can ship you a SIGNED copy! Shipping is for US Media Mail only — if you wish to have this book shipped internationally, please contact orders [at] raintaxi [dot] com for pricing.

the déjà vu

black dreams and black time

$24 (includes shipping in U.S.)

Gabrielle Civil is a Black feminist performance artist, poet, and writer, originally from Detroit, MI. She has premiered over fifty performance art works around the world, most recently Jupiter for the Salt Lake City Performance Art Festival (2021) and Vigil for Northern Spark (2021). Her performance memoirs include Swallow the Fish (2017), Experiments in Joy (2019), (ghost gestures) (2021), and the déjà vu (2022). A 2019 Rema Hort Mann LA Emerging Artist, she teaches at the California Institute of the Arts. The aim of her work is to open up space.

Douglas Kearney has published seven books ranging from poetry to essays to libretti. His most recent collection, Sho (Wave Books), is a Minnesota Book Award winner and a National Book Award, Griffin Poetry Prize, and Pen America finalist. He is the 2021 recipient of OPERA America’s Campbell Opera Librettist Prize, created and generously funded by librettist/lyricist Mark Campbell. A Whiting Writer’s and Foundation for Contemporary Arts Cy Twombly awardee with residencies/fellowships from Cave Canem, The Rauschenberg Foundation, and others, he teaches Creative Writing at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities.

Miré Regulus is a writer, performance artist, public artist, community builder and parent. She works the ‘transformative intersection’ through where her work is sited; through poetry and non-linear, rich, poetical prose; through community participation; and by exploring how body+movement+gesture hold what we know. She works at how we form engaged community and the unique ways we figure out how to take care of each other. One of the Artistic Directors of Poetry for People, she lives and works at the intersection of the BIPOC, queer, political, food-focused and artistic communities seeking to build a more equitable and embodied world.

Sayge Carroll has been tending the soil of community through art and advocacy for more than 20 years. Carroll is a recent graduate of University of Minnesota MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts and Social Practice and holds a BA from the University of Minnesota and is currently enrolled in the Master Gardener program at the University of Minnesota.Through visual art, sound design, and civic engagement, Carroll has devoted their career and life work to connecting ancestral wisdom, lineage and knowledge of natural resources to the present. In their public art and events, Carroll works outside traditional art spaces to reach people in the context of their lives and communities.

Niels Hav

Translated by Per Brask and Patrick Friesen

Anvil Press ($12)

by Alan C. Reese

Niels Hav’s poetry is characterized by both a joie de vivre and a desire for justice, all tendered with a playful and humane sense of humor. Moments of Happiness, his most recent collection, is no exception. The poems teem with life; they are peopled by green grocers, cyclists, and pedestrians alongside recognizable figures like Tintin, Genghis Khan, Charlie Chaplin, and Li Bai. Even though the shadow of death stretches over the poems, they tell us that the point is to live. Like Sisyphus, it is necessary for us to put shoulder to boulder and push upward and onward.

For the Danish Hav, his boulder is poetry. As he tells us in the “Afterword,” “poetry’s first duty is to be an intimate talk with the single reader about the deepest mysteries of existence.” In the face of mind-numbing chores, injustice and idiocy, and the grim realization that no one gets out of here alive, Moments of Happiness is an affirmation of life and a celebratory denunciation of the negative forces listed in “Assumptions,” which include “The unreasonable / The irresponsible / The indecent // The unreflected / The unshaven. The uncontrolled / The unsmooth / The unconditioned // The unthought through.”

Divided into three parts, Moments of Happiness contains uncountable instants of delight. The first part deals with the world of foibles and fools, the jumble of humanity in which Hav counts himself. The second part serves as an incantatory drumbeat that calls forth the specter of mortality: It starts with a sock to the jaw in a poem titled, “Of Course We Are All Going to Die,” and the bleak reality of that fundamental sentiment cannot be tempered even with the image of God wearing shorts. In “A Little Encouragement,” the speaker, feeling poorly, reads the obituaries and is cheered up when he discovers he apparently “hadn’t died recently.” In the last poem of the section, faced with furniture “falling apart,” clothes that “unravel,” and shoes that “wobble,” the speaker takes a walk with his significant other surrounded by “the dead / standing in the shadows” and “dead leaves from last year” that “have blown together / under bushes, on their way into the earth.” Yet they “confidently” dispel the despair by taking hands and acknowledging that “a happiness / flows through the universe.”

The final part of the collection celebrates that realization. In “A Party,” the speaker is again out for a walk, this time solo in the coastal Chinese city of Wenling, when he comes upon a group of card players. They welcome him into their midst, offer him tea and a place to sit. It is in this simplicity and ordinariness, Hav says to us, that we find the real meaning of existence, the holy thread that holds it all together.

Moments of Happiness is sure to provide the reader with just what the title promises, and what more can we ask for as we continue to strive to be, as Joseph Campbell advised us, “joyful participants in the sufferings of the world.” The existential musings gathered here offer comfort and solace in the face of the great abyss.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022

Steve Yarbrough

Ig Publishing ($17.95)

by Eleanor J. Bader

“The Cole sisters were poor girls from the countryside, the kind who up until second or third grade had said fanger for finger,” Steve Yarbrough writes in his sweeping and emotionally resonant eighth novel, Stay Gone Days. Ella, the older sibling, is the story’s good girl: good grades, good manners, and a go-along-to-get-along personality. Caroline is the opposite: feisty and rebellious, she prefers the self-directed learning available in the public library to the classroom.

People in Ella and Caroline’s hometown of Loring, Mississippi, took notice of the pair, and Yarbrough’s evocation of the gender, class, and race dynamics of their all-white enclave crackles. Yarbrough’s portrayal of friendships between girls and sexually pushy boys presents the sordid reality of the 1970s, before terms like acquaintance rape and sexual misconduct entered mainstream parlance, and before feminist activists pushed for consequences against the men who perpetrate these acts.

Ella, a talented singer, flees Loring when she gets a scholarship to Boston’s prestigious Berklee College of Music. She never finishes her degree, however, feeling that her skill and drive are insufficient to make the cut and succeed. Instead, she spends several years waitressing until a chance meeting with Martin, another Berklee dropout, turns into a love affair and then marriage and life as a stay-at-home mother of two. Economic security follows as the fledgling record label that Martin co-owns takes off and thrives.

Caroline, on the other hand, remains in Loring after Ella leaves, and she opts for what she calls Stay Gone Days, skipping classes and doing whatever she can to find adventure. Like Ella, Caroline eventually leaves Mississippi, but once gone, she maintains only sporadic contact with her sister and their newly remarried mom, a trickle of communication that quickly sputters out. Her life is something of a blur as she moves from state to state, taking low level jobs and entering and exiting relationships that, for the most part, mean nothing to her. For a while, this lifestyle satisfies her.

Although Yarbrough writes without overt judgment, the unfolding story is a showcase for the ways bad luck can intersect with bad choices. In this case, when Caroline is in her mid-twenties, she finds herself scrambling for safety after hooking up with a wannabe actor turned violent grifter. After she heads to Europe to evade criminal prosecution for her unwitting role in a theft that left a store clerk dead, Caroline’s terror and desperation are palpable. But this wily heroine is a survivor. Using a forged college transcript, she finds work as an off-the-books English teacher, moving from Brno to Bratislava to Budapest to Prague before finding a higher-paying and more permanent position in Warsaw. Stability follows. So does fame as she begins writing in her spare time and is soon highly lauded for her skill with words.

Years go by, and while the sisters frequently think of one another, there is absolutely no contact between them. Yarbrough is masterful at creating a milieu that allows their estrangement to fester and flourish. Indeed, his ability to describe emotional complexity is astonishing and extends beyond the sisters’ relationship. For example, the minute annoyances that bubble up in most long-term romantic relationships are presented so matter-of-factly that they are simultaneously heartbreaking, riveting, and wholly recognizable. Silences replace easy banter, despite the fact that Martin loved Ella “more than anybody or anything. Why had it become so hard to show it? He’d die for her if need be. He sometimes felt as if he already had.”

In addition, Stay Gone Days covers territory that goes beyond sibling and marital conflict. By zeroing in on the necessity to forgive oneself for trespasses large and small, it posits a cogent moral reckoning. What’s more, a vast number of human foibles and failings, such as regret, atonement, and reconciliation, are rendered in prose that is breathtakingly beautiful and tremendously moving. Ella and Caroline have a brief reunion that temporarily returns them to Loring, but it becomes clear that the many omissions—the many missed moments of joy and sorrow in each of their lives—cannot be recovered, giving the novel lasting gravitas.

Wise, tender, and honest, Stay Gone Days forces readers to confront the inevitability of aging and the choices we make to maintain or sever family ties. It also forces us to consider the long-term residue that remains long after we leave our childhood homes. Stay Gone Days brings Ella and Caroline home again, but it is a home that neither of them recognizes. Whether they can construct something new in its stead remains an open question.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022

Kim Fu

Tin House ($16.95)

by Trisha Collopy

A girl grows feathers along her legs. A swarm of out-of-season June bugs overwhelms a rental house. A sand creature tugs an insomniac into sleep. A giant blob of “brainless multicellular organisms” is spotted off the coast of Hawaii. Signs of the monstrous surface throughout Kim Fu’s Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century, but it’s unmet human need, lurking in the subconscious like unexploded ordnance, that unleashes the true monsters in these twelve shape-shifting tales.

Fu’s opening story, “Pre-Simulation Consultation XF007867,” sketches a near future where technology has become a mediator for human emotions. In a stripped-down chat transcript, a nameless client and operator of a holographic simulator debate whether the operator can bend the rules to grant the client’s sole wish: a day in a botanical garden with their now-dead mother. As they tangle over the platform’s fine print, the operator reveals a world where those who can afford it, “the whales,” visit the simulator again and again to live out dreams of having superpowers or wild sex, of completing a creative work or acting out violent racist fantasies. The platform is just a machine, the operator says, “Your brain creates the majority of the content.”

Those words foreshadow many of the stories in the collection, where Fu combines unexpected creatures and awkward social interactions to build a sense of unease. One of her sharpest stories, “#ClimbingNation,” raises questions about social media, celebrity culture, and how both become proxies for our emotional lives. The story opens as April arrives at the memorial of a climber, Travis, who lived in her dorm in college, but who she’d never encountered until his posts exploded on social media. Though April has no interest in mountaineering, she’s fascinated to realize that “someone she’d plausibly known had five hundred thousand followers on Instagram, the population of a midsize city.” She watches hundreds of Travis’s short videos, the freeze-frame intimacy of the small screen allowing her to zero in on “his view of the world from above, geographic and breathtaking,” as she hides in her dark bathroom, eating chips alone.

But that illusion of intimacy is shattered when she intrudes on the private space of his family’s grief. As April makes her way through the room at Travis’ memorial, she worries that his sister, Miki, and his climbing partner, Zach, will catch her in the lie. When the room empties out, April lingers, hiding behind helpful tasks, cleaning up after guests, washing dishes. Then Miki makes a chilling confession, and April is suddenly complicit, burdened with emotions no longer mediated through a screen.

If the gothic stories of Carmen Maria Machado use the monstrous to reveal hidden desires, ones we’ve forced into the subterranean spaces in our subconscious, Fu’s stories serve to recreate the shock of feeling in a landscape of disconnection. A thread of emotional disconnection runs through many of the stories in this collection. Characters are unable to ask for what they want, whether it’s a traditional wedding (“Bridezilla”), sexual release (“Scissors”), or a good night’s sleep (“Sandman.”) In “June Bugs,” need becomes monstrous as a woman flees an abusive partner. In “Twenty Hours,” a couple kill each other violently to give a jolt to their relationship.

The collection’s final story echoes the opening, in a near future where a creator-technician tries to reconstruct what has been lost. A highly transmissible virus has hit everyone on the planet, erasing the pleasure of taste and “the push-pull addition” of food. [200] Allie, a web designer, starts a side hustle building elaborate sensory experiences for those who can’t let go. Word spreads of her abilities, and soon she has a furtive list of clients, each hoping to reexperience the shiver of delight they had found in their favorite meal. When one client challenges Allie, accusing her of being a con artist, she retorts that she doesn’t consider herself an artist at all. But then she realizes that isn’t true:

When she submerges a client in bouncy balls, when she carefully sets their leg hair on fire, when she contrives a thousand ways to make twitch this now-insensate limb, she feels like a poet, making concrete something that no longer has concrete manifestation in the world.

Fu ends her tales of the monstrous on a hopeful note: We can know joy even in a world that is failing all around us. Our spirit sparks in the ruins.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore