Christine Wertheim

Christine Wertheim

Counterpath ($30)

by Maria Damon

There is a way that language shudders into the very flesh, not because our flesh is made sense of through language, but because language emerges from and returns to the body.

—Jefferson Hansen (thealteredscale.blogspot.com, September 21, 2104)

What could be more fun than a tract of feminist psychoanalytic philosophy wearing the cloak of visual and sound poetry? I suppose one might think of several hundred candidates for such a status. And yet, feminist philosophy has been far more playful than one might initially assume. In fact, play has been one of its constituent elements, if only to offset the seriousness with which a patriarchal discourse top-heavy with “phallogocentrism” (the term itself is a feminist spin on “logocentrism”) takes itself. For every Socrates or Apollo, there is a Baubo. For every Descartes, there is a Cixous, whose “Laugh of the Medusa” certainly both thematizes and enacts its affirmation of a terrifyingly comical “écriture feminine.” For every Freud, there is a Bracha L. Ettinger, in fact for every Freud there is a . . . Freud. You get my drift. Not that male philosophers and writers don’t also play with language. Derrida, Lacan, Thoreau, and so on have been positively drunk on puns and the thoughtscapes they catalyze. The gender war of words and laughs is not really a war on the linguistic front but an exploration into the enabling possibilities of language itself.

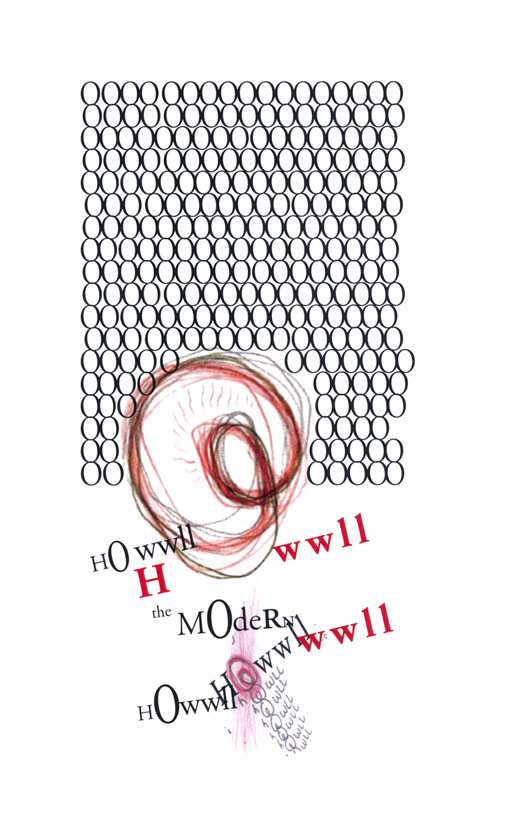

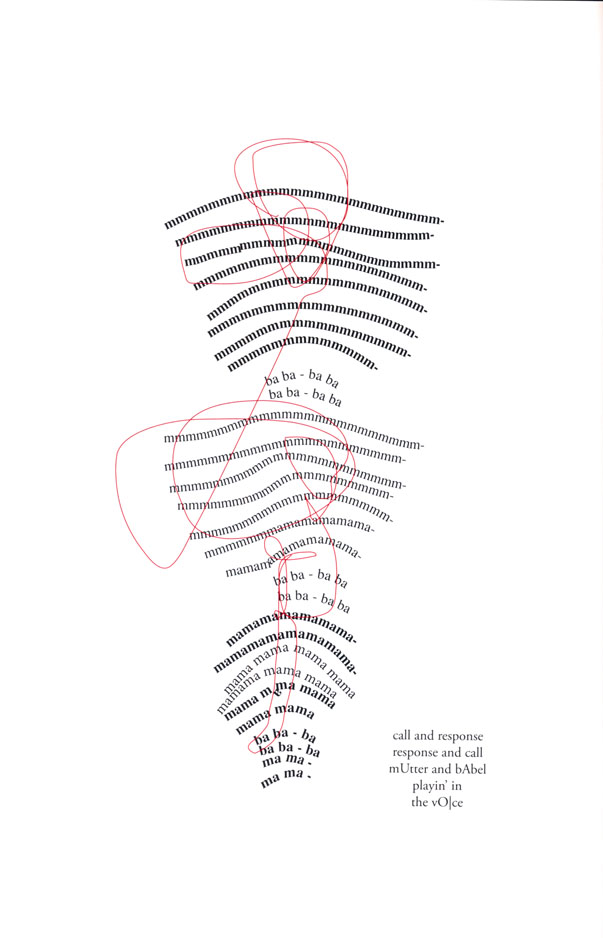

Christine Wertheim’s mUtter-bAbel partakes of this serious-as-your-life whimsy in its evocation of the emergence of a human child first into the world and then into language, mediated by the osmotically omnipresent M / Other / Utter / Outh / Yth. In dazzling graphics that blend sound and visual poetry, the text unfolds as a series of cries, howls, murmurs and whispers that are themselves illustrations: digital and manually produced manipulations of handwriting, typeface, and other alphabetic technologies, spelling, in wavy and endlessly radiating replication, “thIsOng’s of the-M-any-Others’ flOw-er-ing vOIdSe,” or fat white snakes of undulating “sssssssssssssssssshhhhhhhhhhhhh!!!!!!!!!!!!”’ s swarming across a black page. (The “I”s in all of the cited materials are actually vertical slashes, cuts that undermine the assertive declaration of the capitalized ego implicit in the first-person pronoun conventionally associated with the singular vowel or its upper-case incarnation anywhere in an English-language inscription.) The primordiality of emergence and the persistent mother-child bond as bodied forth in flowing/fragmented language has been written about by Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray, and certainly others, but never so primordially, never so bondedly, never so embodied.

And the picture immediately becomes more complex, as the satisfactions of entering language with a triumphant “I’m meeeeeeee”-ness inevitably give way to certain inadequacies and conflicts when “mOther’s voIce turn[s] from an invitation to an imposition.” Handscrawled, messy, border-ignoring holes drawn in red and black join the elegant fonts and waves of digital graphics, as the gleeful meeeee-ness turns to a howl/hole of dissent and despair, a resistance to a kind of trap that, paradoxically, denies difference rather than aiding individuation. The primal is complicated by discomfort and rage. However, what in some psychoanalytic circles would be called the intrusion of the “law of the Father”—i.e. language, structure, hierarchy, etc.—is nowhere yet identified in Wertheim’s masterpiece as gendered or explicitly named. Nor does the father appear at all in the same way the mother does, except obliquely as the “babel” of the title. (mUtter-bAbel=mOther-fAther as the tower of babel defeats univocality, dissonantly echoing the fluid “money money money / water water water” of Theodore Roethke’s “The Lost Son,” where this phrase is a visceral response to the “lamentation being summed up,” the thirst for “the old rage, the lash of primordial milk!”) The drama, though internally marked by smears, bloody/fecal/salivary leakage and verbal/psychic violence, is a drama between mother and child, struggling for otherness/sameness in larval battle. A strange metamorphosis in the form of a power shift takes place. Paradoxically, “the-m-Others” emerge not as the powerful shapers of a child’s experience, but the victims of the child’s unrealistic expectations of life without inconsistencies or frictions. That is, as will become clear, the privileged of this world come to expect to be permanently infantilized, while projecting their rage onto the-m-Others—the poor, the have-nots—for having incompletely served their (the permanent children’s) needs.

This becomes explicit in “Interlude,” or

speculations on the effects of the shIt-hOwle in adult society

or

the politics of dung-prattle[,]

which adopts an essayistic, discursive tone even as the now extremely dense aggregate of hand-scrawled holes and typed letters take the form of mouth-holes, continents (Africa), bodies, parasitic speaking shapes. Expository prose, the language of the father (or, as they said in the old days, “phallogocentrism”), enters like a foreign tOngue, spreading order even as ordure spreads and chaos raises the stakes of what has been a private, dyadic conversation.

The final two chapters, “ShIt People” and “Pamela Aber,” focus this dysfunction in two case studies in which the larger socio-political violence of this seemingly private difficulty are spelled out. In these sections, the father trope appears horrifically in two case studies of the consequences of difficult individuation. The murders of young women at the Mexican/US border as the ultimate detritus of “shit people” (people unwanted, extruded from the MotherNation’s body back and forth between MotherNations, povertymisery compounded) indicate a surplus of rage, bloody self-laceration of a socius that cannot meaningfully expand to accommodate all its constituent beings. And then there’s the also-horrific testimony of Pamela Aber, a teenager who escaped from the Lord’s Resistance Army, Joseph Kony’s coerced aggregate that terrorizes Uganda by forcing its own youth to participate in killing and maiming the populace. Aber describes an incident in which orality is used to grisly and fatal ends: Kony ordered a group of children, on pain of death, to bite a girl to death, despite their pleas that they/she be spared this atrocity. When she did not die, despite profuse bleeding and wounding, they were then forced to club her until she finally died. This perversion of primal orality to kill rather than to nurture or be nurtured is an extreme exemplar of an adult’s need that children satisfy his insatiable desires for power through a deformed nursing ritual that destroys the psyches of the children; all are “blinded by blOOd.” And worse, this horror, beyond its spectacular humanitarian transgressions, is not an affront to the aims of imperial powers (i.e. us/US) who support the Ugandan government, whose deliberate destabilization of an ethnic group (Acholi) led to this political debacle. Thus, what at one level appears to be a deformity of normal human relations is simply a routine side effect of business as usual at the political level.

The way in which the book progresses tonally, discursively, graphically, and sonically from a terrain of chaotic but exciting possibility and discovery through an inevitable complication to the horrific effects of its irresolvability is masterful (with all the caveats that word enfreights) even as it plays with and roots itself in syllables and entities as primal as “me, “mommy,” and (the somewhat ghostly throughout) “babel.” The level of this achievement takes my breath away, that breath that is the ground of language, leaving me disembodied until I remember the art and care with which it was birthed.

Anthology of Contemporary Bulgarian Poetry

Anthology of Contemporary Bulgarian Poetry