Interviewed by Connor Bjotvedt

Interviewed by Connor Bjotvedt

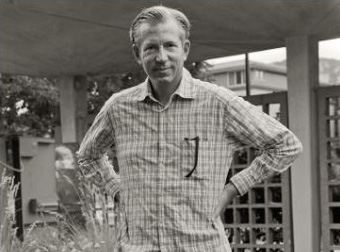

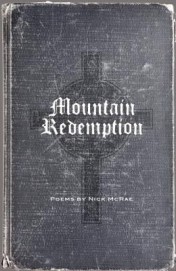

In Mountain Redemption (Black Lawrence Press, 2013), which won the Fall 2011 Black River chapbook competition, poet Nick McRae focuses on the role of tradition and the emergence of Christian religions in mountain towns. Elegiac in tone and narrative in structure, the book explores life and death in these mountain communities through the lens of Biblical stories and motifs.

In addition to Mountain Redemption, McRae is the author of The Name Museum (C&R Press, 2014) and the editor of the anthology Gathered: Contemporary Quaker Poets (Sundress Publications, 2013). He earned his MFA in creative writing from The Ohio State University, and is currently a Robert B. Toulouse Doctoral Fellow in English at the University of North Texas.

Connor Bjotvedt: One of Mountain Redemption’s themes revolves around rural community. I see a type of “rural religion” in the opening poems, centered on the life and death of animals, with humans having a caretaker relationship with the animals that surround them. The people who inhabit the small town setting have also developed their own customs, such as in "Take, Eat," in which the crawdad becomes a kind of communion. Since religion comes back later in the book in a more structured, “church” sense, why does the book begin in the rural community?

Connor Bjotvedt: One of Mountain Redemption’s themes revolves around rural community. I see a type of “rural religion” in the opening poems, centered on the life and death of animals, with humans having a caretaker relationship with the animals that surround them. The people who inhabit the small town setting have also developed their own customs, such as in "Take, Eat," in which the crawdad becomes a kind of communion. Since religion comes back later in the book in a more structured, “church” sense, why does the book begin in the rural community?

Nick McRae: I like the phrase "rural religion"; it definitely feels appropriate to my sense of the book, particularly the first section, as you pointed out, and the third section is almost as strongly tied to that idea, albeit in perhaps a more personal way.

When Diane, my wonderful editor at Black Lawrence Press, asked me for a one-sentence description of the book to send to distributors, I think I used a phrase like "Christian mythos and the legacy of Southern ruralism" or something like that in describing it. Your phrase is probably better, and certainly more concise. But yes, that's something I think about a lot: the myriad ways that symbolism from Christian mythology manifests itself in rural communities. Usually this involves some sort of violent act. You mention the crawdad in "Take, Eat," for instance; there are also many images of dead or dying deer, which is something that stands out in my mind as one of my central connections to violence during childhood. One bit of my standard between-poem banter at readings is that I have no personal antipathy toward deer. I don't, of course, but for some reason it remains a humorous thing to hear someone say.

This type of violence echoes, to me, much of the sacrificial imagery of the Bible: the literal sacrificial lambs of the Old Testament, the figurative sacrificial lamb (Jesus) in the New Testament. There is a way in which the Christian tradition of blessing food before eating it completes a kind of mimicked sacrificial rite, whether that food is the deer or crawdads in these poems or the fruit in "Persimmon," where the violence against the trees requires eating as a kind of atonement for that violence. The danger is that it becomes a justification for violence instead of an atonement for it. Acknowledging that danger, I nonetheless try to honor those traditions as much as I am able to.

CB: As a poet of faith, do you feel that you are narrowing your reader base by including religious motifs and stories in your work?

NM: This kind of concern—whether content that touches on a spiritual tradition might push away readers who are not from nor have any interest in being part of that tradition—is something that we poets think we need to worry about, but I have found that fewer readers than we might expect will reject a poem simply because it touches on religion. It will happen, yes, but I have found it to be somewhat rare.

I had a teacher once who would often say something to the effect of "I don't much go in for the churchy stuff" when confronted with a student poem with religious content, but even he, who voiced reservations right up front, would find things to value in those poems provided they did more than rehash and re-present religious doctrine.

That seems to be the case with the majority of readers. Poems that truly grapple with religion—poems that question it, look at it from new angles, take old ideas apart and rebuild them into something else, something new, something unexpected—those poems tend to feel honest, while for even the most traditional people of faith (I, for one, fall into the considerably nontraditional side of things), poems that deal in unquestioned dogma often feel dishonest, no matter how sincere the belief. There's something about doubt that conveys honesty in ways certainty can never achieve. And most people will give a poem the benefit of the doubt as long as it's an honest poem.

CB: In “Pessimist's Guide to Miracles” you move from a deer, the main animal figure in the earlier poems in the book, to a donkey. This transition comes as the book moves more into the realm of the established religion rather than the folk religion. Is this a tie to the Biblical story of Joseph and Mary?

NM: That's an interesting and perceptive reading of that shift. I didn't have Mary and Joseph's donkey specifically in mind when I wrote the poem, but it does seem to me that, after the lamb (and maybe the serpent and the dove), the donkey is the animal with perhaps the strongest symbolic resonance throughout the Bible and wider Christian culture.

Mary rode a donkey into Bethlehem, as you mentioned. Jesus rode a donkey into Jerusalem during the Triumphal Entry, just before the Last Supper, which is why Christians celebrate Palm Sunday. The specific donkey that inspired the poem was Balaam's, from the Book of Numbers. His story goes like this: One day, Balaam was riding his donkey down the road when an angel, visible only to the donkey, appears there, intent on killing Balaam. The donkey refuses to approach the angel, but Balaam doesn't know the donkey is saving his life, so he begins to beat the donkey. Suddenly, the donkey is given the power of speech, and it asks Balaam why it's being punished for saving his life. At that moment Balaam, too, sees the angel, and he knows the injustice he has perpetrated.

It's a totally weird story, which is one of the reasons I like it so much, and I think it can be read as a fable; here we humans are, unable to see what is really going on around us, and so in our ignorance we lash out in violence because we don't know what else to do. That is one way in which the donkey in this poem is somewhat like the deer in other poems in the collection; our violence toward these creatures reveals the centrality of violence in how we respond to our world as a whole.

CB: Throughout the book you explore the notion of death; for the majority of the poems, the speaker runs from death and killing because he fears death himself, like in “Thanatophobia on Shinbone Valley Road.” Yet in “St. Nicholas of Lycia, Defender of Orthodoxy, Wonderworker” the speaker, a priest, is told of a murder and he runs to claim the bodies, forsaking the seal of the confessional; he then strips himself of his clothing and plunges his arms into the barrel where the bodies are stored. Does this action suggest there is redemption in death?

NM: I think the priest in "St. Nicholas" doesn't see redemption in death so much as he sees in it the necessity of remembrance. In "Thanatophobia" and the poems like it, the speaker turns away from death because he is afraid of dying, yes, but also because he is unable to deal out death, even for the sake of mercy, the way that he has been taught is good and proper. He resists his complicity in it, just as the priest resists his complicity in the murder of the three little boys. The priest is unwilling to stand by and let the institutions he believes in—the seal of the confessional, the forgiveness that is in the act of confession—act as a shield for the murderous butcher while the butchered children are anonymous and forgotten. He wants to feel their names on his skin, as he puts it, so their death won't be forgotten. Which is sort of the aim of poetry, I think, especially elegy, of which there is much in the collection.

CB: In “Psalm 137,” you take daily life and explore it as almost a ritual, one that has been lost to newer generations. Why did you begin the final section of the book with this poem? It seems to fit more with earlier pieces such as “Mountain Redemption.”

NM: I spent a lot of time in indecision over where to put this poem in the collection. On one level, you're right that it would have fit cleanly into the first section, possibly with "Mountain Redemption" as you suggest. Both poems talk about the mythic dimensions of bygone times and bygone people, so that might have been a good match. However, "Psalm 137" is also an elegy—an elegy for a way of life—and so it also fits at the beginning of section three, just before the series of elegies to my grandfathers.

In the end, I went with that elegiac impulse and used the poem as a bridge from the larger mythologies to the particularities of the men I wanted to elegize. And it was important for me to begin the last section of the book with this poem because it doesn't (at least as I see it) so much call for the old times and old ways to come back as it questions the desire for them to come back—and also whether they were ever real at all, or just mythos.

Psalm 137 in the Bible is an elegy for the Israelites' lost homeland. They have been taken as slaves and forcibly removed by the Babylonians, and their captors, adding insult to injury, ask to be entertained with a song about Zion. To this, the weeping Israelites can only answer "How shall we sing the Lord's song in a strange land?" So far from home, from what was lost, how could their song have any meaning? I think this poem wants to ask a similar sort of question, something like: How can I sing of this home I have heard of all my life—this way of living and being in the world, where altars and tractors and skinning knives and hymns are the very fabric of reality—when I have only glimpsed the edges of it and when I only half believe in it? Is it a "home I only almost had," as the poem says. A real place, and a bloody place, but a mythic place nonetheless.

CB: The final poem, titled “Apple,” seems to involve both the Biblical motifs as well as the folk religion of the book. You enter the realm of not knowing and remembrance through the memory of the speaker, who wants to bite into the apple and regain the knowledge of its taste, much like the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden. He remarks on the fact that it is alone in the field that he has found it in, and that there is no child nearby to taste of it like he did. The speaker decides to bury the apple rather than eat it, and waits for it to grow and to blossom fruit for the next generation. I see this as the final salvation of the mountain towns—a way to unify Biblical and folk religion rather than strictly conform to one or the other. Do you see this poem as a manifesto?

NM: A manifesto? I've never thought of this poem that way, but I like that idea a lot! It would feel good to have the confidence of a manifesto writer (manifestoist? manifestor? Uncle Fester?), though to my mind if the poem is making any kind of statement, it is something much more tentative. But then, to be tentative is just sort of my nature.

This poem, even more than most of my other poems, means different things to me at different times. Right now, thinking of it in the context of your challenging and insightful interview questions, I find myself wanting to read the poem as an exploration of faith and memory. Finding the unlikely apple in the middle of a field, the speaker remembers the painful immediacy of the quince fruit of his childhood. He could eat it and taste the past. He could leave it where he found it and let someone or something else have it. But he can't do that. Instead, he buries it where it can be his and only his, and maybe someday it will sprout and bloom again.

Maybe the apple is like the faith—the powerful, immediate, uncompromising belief in mysteries like God and salvation and ultimate good—that children can experience in a simple and vivid way that most people, once childhood has passed, cannot access in the same way. I think of my faith as something kind of like the apple here: something that is mine and mine only, buried in the black and wormy loam of the physical body, where maybe it will simply die or maybe it will flower. In my mind, that's what faith tends to look like: an in-between state, an uncertainty, a hopeful doubt.