Colin Wilson- Photo by Maurice Basset

by Eric Lorberer and Kelly Everding

Colin Wilson burst onto the literary scene in 1956 with the publication of The Outsider; since then he has written over 100 books in nearly every conceivable genre. In the following interview, he talks at length about what led him to become such a prolific writer and about the ideas that run throughout his work.

Excerpts from this interview, as well as reviews of several of Wilson's recent books and an essay about his work, appear in the Winter 1997 issue of Rain Taxi. Purchase this issue now!

Rain Taxi: Tell us a bit about your background, the publication of The Outsider, and the backlash that ensued. Did it affect your writing in any way?

Wilson: My background was working class: my father was a boot and shoe worker who earned about three pounds a week throughout the 1930s—about ten dollars in modern money. He was a kind of determined anti-intellectual; he'd been a boxer for awhile, but he lost the fight that would have turned him into a professional. He was a born countryman, really, but unfortunately lived in a city and had to work in a factory all his life. The result was that there wasn't an enormous amount of money around. Fortunately, I was very bright at school, and won a scholarship to a secondary school, which is the kind you have to attend in order to go on to university. I'd become fascinated by science at the age of ten—I read nothing else for years, except science fiction, which I managed to get a hold of during the war, those old American magazine such as Amazing Stories, which you could get on exchange in various shops in Leicester. I wanted to become a second Einstein. Unfortunately, I left school without the necessary number of credits. I was invited to take the exam over again, but this was going to be several months away. So when I left school in July 1947, I went to work in a wool factory, which was the first job offered me by the employment exchange. It was heavy work, lugging around crates of wool, and I hated it—it started at six in the morning, finished at six in the evening, and it seemed to me to be completely exhausting and boring.

I had by this time discovered poetry—not at school, where we didn't get taught much of it, but through a book called Practical Knowledge For All, which I bought at a church bazaar, and which contained courses on all sorts of subjects, from aeronautics and biology to philosophy. So in this state of total depression at my prospects, at the notion of having to work like a bloody rat on a treadmill for the rest of my life at jobs I hated, I used to go home in the evening, completely miserable, take myself off to my bedroom, and read poetry. I'd start off by reading the most depressing poetry I could find, things like Eliot's "Waste Land" and "Hollow Men," James Thomson's "City of Dreadful Night," the poetry of Edgar Allan Poe, like "For Annie," in which he says the best thing is to be dead. But of course this poetry would exercise a kind of cathartic effect, so that after about a half hour of reading I began to get more and more cheerful, and I'd end up by reading poems like Milton's "L'Allegro" and the love lyrics of James Herrick. I was also at that time reading a great deal of Shakespeare, and I absorbed that the same way as everything else. I hadn't yet developed a dislike of Shakespeare because of his basic pessimism. And of course the other person I admired tremendously was Shaw—I read my way completely through Shaw from beginning to end.

Anyway, one day when I called at school to return some mathematics books I'd borrowed, the headmaster offered me a job as a lab assistant, and this seemed absolutely wonderful: doing school hours, not having to work Saturdays, etc. But I soon discovered, to my horror, that I'd completely lost interest in science! There were some ways I found school as depressing as factory: my physics master was a real bastard who took every opportunity to be nasty. In due course, the exams came and it became completely apparent that I'd lost my interest in science; the headmaster came and said, you know, do you want to stay and pull your socks up, and I said no it's no good, I'm sorry, I just don't have any interest in science anymore. So I left school. I went to the labor exchange and they recommended me to take a job in the civil service, in a tax office. I found that even more boring than the factory or school; there was nothing very interesting to do except sit and file tax forms. What I wanted to do was use my mind: I wanted to write. I had started a journal; I bought a huge notebook and just began pouring my thoughts and feelings into it—which is an excellent way of learning to write. I particularly poured my depressions into it, and one day when I'd been writing about my absolute fury with this bloody physics master, I suddenly decided to commit suicide. I went off to school, to the evening class in analytical chemistry; I went over to the reagent shelf, took down a bottle of potassium cyanide, took off the stopper, and I was about to swallow it when I suddenly had an extremely clear vision of a few seconds in the future, of a horrible burning in the pit of my stomach, and therealization that I would have done something irrevocable. Oddly enough, it was as if I were two persons: I could see this little idiot Colin Wilson with all his stupid emotional problems, but there was also me, and I didn't give a damn whether Colin Wilson killed himself or not—except that if he did, he'd kill me too! And quite suddenly I was overwhelmed by a tremendous feeling of exultation. I put the bottle back on the shelf and rejoined the other students, and for two days I felt an immense sense of euphoria, which only gradually leaked away.

Anyway, the civil service was a horrible bore; I took my exams and to my disgust passed them easily, and became an established civil servant. I went to a town called Rugby which was extremely peaceful and which I hated, and worked there in the tax office, disliking that as much as I disliked everything. By that time I was almost 18, and the time came for me to do my national service; I went into the RAF, where the first eight weeks were spent square-bashing, and suddenly I felt absolutely fine: I was using all my energies up, sleeping well at night, eating enormously, also doing a bit of writing when I got the chance, and life seemed much nicer. But unfortunately when the square-bashing was over they assigned me to an antiaircraft unit as a kind of clerk, and I was back in effect to the civil service. I got more and more bored and fed up, until finally one day, when I typed a letter and the adjutant suddenly shouted at me, this is absolutely filthy Wilson, aren't you ashamed of it, and I said furiously, no. The adjutant looked very surprised and told me to go and wait in his office, where to my surprise he was quite sympathetic and said, now you go and see the MO, and if he will say that you're emotionally unsuited to work as a clerk perhaps we can get you transferred into something you prefer. When I went to see the MO I suddenly had an inspiration: I told him I was a homosexual, which I wasn't, but I knew all about homosexuality because one of my closest friends in Leicester, a character called Allan Bates, was homosexual and sort of a cultured type, and we got on tremendously well. He always said he wanted me to be his lover and all the rest of it, but of course it did just not appeal to me.

To cut a long story short, within about six weeks I was out of the RAF. I had that feeling that fate was deliberately hunting me from pillar to post when I read those lines in W.B. Yeats: "They are plagued by crowds until / They've the passion to escape." I had the feeling that this was what fate was doing to me: plaguing me until I had the passion to escape. I vowed I would never again work in an office. The first thing I did was get a job at a building site; I felt at least hard physical labor was better than sitting in an office with that increasingly stifling feeling. My father was absolutely horrified at this job, and several others—I also worked as a nabby, which is a ditch-digger in America, and my father thought, my God, the clever one in the family, and here I was working as a nabby. The result was that one night he suddenly told me to get out; I borrowed a few pounds from my grandmother and pushed off on the road. I hitchhiked down to Kent where I got a job as an apple-picker, was allowed to sleep in a derelict cottage whose roof had huge holes in it, and after this, on to Dover, and managed to get across to France with less than a pound in my pocket. I spent some weeks in Paris at the so-called Academy of a man called Raymond Duncan, who was the brother of the famous dancer Isadora. He wanted to teach me how to live according to his principles which he called Actionalism, which is basically be as much of an intellectual as you like but be capable of building a house if necessary, or mending pipes, or anything else. And I quite agree with him actually, but it didn't work out: I got bored there. I was always bored because what I wanted was to be a writer.

I came back from France finally, got a job in Leicester in a steel foundry, and there I met the works nurse, a girl called Betty: she ended by inviting me back to her flat and I ended by seducing her. To once again cut a long story short, my parents insisted that I marry her, and so, again to my disgust, I found myself a married man at the age of 19. I went to London, succeeded in finding a home for us after a great deal of effort; Betty moved down and had the baby, a little boy, Roderick, but in those days landladies didn't like babies or pets, so we moved several more times over the next 18 months. At the end of this time Betty went back to stay with my parents while I stayed on to look for a place for us, by now thoroughly fed up with the whole business. I'd been working in factories throughout my marriage, and I was also busily writing. Betty borrowed some money from her mother so we could take a flat, and the Irish woman who was letting it seemed to me a nice person, but when we'd agreed to take it Betty sent me a telegram saying she'd changed her mind, simply because the Irish woman refused to have a legalized agreement—I assume she was probably right although I trusted the woman. And that really was the end of our marriage. I was quite relieved, and shortly thereafter I went to France, so I suppose technically speaking I deserted her, although in fact she'd written me a letter saying she was sick of the marriage too. I ended up in Paris; Bill Hopkins, a writer I'd met in London, came to join me there for a bit; he was trying to launch a magazine and wanted to explore French printers to see if they were cheaper. Finally, in August or September 1963—I'd been separated from Betty since January—I came back and went to work in a large store in Leicester called Lewis'. On my first day there, the girl who took the new trainees up in the lift, she was a slim girl, I didn't find her particularly pretty, I thought her nose was rather large, but I expected her to talk with this horrible Leicester accent—the equivalent of the deep south accent in America—and in fact when she spoke with a sort of cultured voice, and she had the sweetest smile I'd ever seen, she absolutely beamed good nature. I was completely smitten, but I could see she'd had an engagement ring on, so I just suppressed this feeling of, you know, my God she's adorable, but in point of fact although she was engaged to a student she'd known at Trinity College Dublin and was about to go and marry him in Canada, things worked out so that she ended by coming to London with me instead. And of course we're still together after 44 years, largely because she's so good tempered—I'm not difficult too live with but I do tend to get rather impatient being a workaholic.

Anyway, I moved back to London, quit or got sacked from various jobs . . . I really had that feeling of being driven from pillar to post by sheer frustration. The frustration that had been going on for seven years seemed like it had been going on for eternity. I got the sudden idea: I was spending about three or four pounds a week on rent, but why didn't I instead buy myself a tent and sleep out in the open, in one of London's parks or something. And this I did. At first I slept in a field opposite the factory that I was about to leave, but then I realized the tent was rather visible and that it would be much simpler if I got myself a waterproof sleeping bag. I left all my books and that sort of thing with Joy, who'd started working in a big store down in Oxford Circus, and subsequently

became a librarian. She also got thrown out of one lodging because the landlady objected to me turning up at about eight in the morning to have breakfast with her. (Joy also had a series of neurotic landladies.) Finally I began to go down to the British Museum and began to work on my first novel, Ritual in the Dark. I'd sleep on Hampstead Heath, leave at daylight and cycle down the hill to a little cafe where I could get tea and bread and dripping for about sixpence, and then go on to the British Museum and spend the day, for example, reading up on the actual accounts of the Jack the Ripper murder cases in the Times for 1888, because Ritual in the Dark was based on a sex killer. I discovered in the British Museum a book called The Sadist, which is about a sex killer who'd committed a number of murders in Dusseldorf during the 1920's, and I got this out and read it with absolute absorption, as it once again provided me with the kind of background I needed for my novel. I should mention that I'd started this novel when I was still married to Betty, and had gone around the East End looking at all the Jack the Ripper murder sites that still existed.

When the winter came, having got soaked once or twice, I was forced to move indoors again. And it was when Joy went home for Christmas—I didn't have enough money to go to Leicester—that stuck in my room, eating egg and bacon and tomato for my Christmas dinner, I suddenly got the idea for a book called The Outsider in Literature, and began taking notes for it in the back of my diary, which I still have. This got me quite excited; I wanted to show just how many Outsiders there are in literature, these people who you might call 'in-betweeners', people who are a little too intelligent to put up with the kinds of jobs and lives they're expected to endure in modern society, and yet not intelligent enough to be able to dictate their own terms. But I could also see that all people who are, so to speak, in the wrong place, in the wrong position, are Outsiders. So it was not only these people who fell between two schools, but people like Fitzgerald's Gatsby, who in practice is a bootlegger and a gangster yet who nevertheless is a total romantic. That was what fascinated me, the Romantics of the nineteenth century, and what has been called the eternal longing: this feeling that there must be a better way to live than this, that these moments of ecstasy, these moments of deep peace and serenity which I experienced when reading poetry, must be attainable on a more everyday commonplace basis. It seemed intolerable only to be able to experience this when reading poetry, or in what William James calls "melting moods," and have to spend the rest of your time working at some job you hate. Again, a character like Hamlet is a typical Outsider: he's stuck in a kind of emotional position which he finds completely disagreeable. I agree with Shaw's analysis of Hamlet, which is that according to the old code of morality he ought to be murdering his uncle and perhaps even his mother, and yet he instinctively feels that this is not the right thing to do; he's living by another code of morality, a higher code.

As soon as Christmas was over, I cycled down to the British Museum to work on The Outsider in Literature, and as I was cycling there, I remembered a book I'd read by Henri Barbusse called Under Fire, about the first world war. It mentioned in the introduction that Barbusse had first become famous when he'd written a novel called L'Enfer—Hell—about a man living in a boarding house who discovers a little hole through which he can see into the next room, and he spends all his days watching the people come and go in the next room, and he really struck me as the archetypal Outsider, looking through a hole into other people's lives. So when I got to the Museum I found L'Enfer, read it through from about mid-morning until about three in the afternoon, and then simply copied out a passage of the book: "In the air, on top of a tram, a girl is sitting. Her dress, lifted a little, blows out. . . ." I found this very interesting because the sexual theme was basic in my work. Ritual in the Dark was about that; there was a scene in which the hero, Gerard Sorme, has spent the afternoon making love to his girlfriend about seven times, and is utterly sexually exhausted, and thinks, isn't it wonderful to be finally free of this perpetual sexual itch, and then he goes out to get the milk from the doorstep of the basement, and looking up can see up the skirt of this girl who's passing the area railings, and instantly experiences a wild desire. So I knew absolutely what Barbusse meant, this business about "It is not a woman I want—it is all women."

By this time, I was working in a laundry; it was sort of a dreary laboring job which involved lifting tin baths on and off a moving belt all day long, and if you weren't careful you slashed your hands because a lot of them were very rusty. What finally disgusted me with the laundry was, I had a pocket sized journal, which I filled with ideas and so on, and this was stolen one day; probably whoever stole it had opened it casually and seen some reference to sex, and took it away. I was so angry about this I even offered a reward, but it never turned up. So I gave my notice, went to the labor exchange, and was told that a new coffeehouse was opening in the Haymarket, and that they wanted a washer-up. So I signed on. And I found this a very pleasant job after all the previous jobs I had; quite suddenly fate had ceased to harrow me. Most of the other people working there were young drama students, and this was very pleasant; I'd always worked among working men and women, and to be around students hoping to become the great actor or actress was tremendously stimulating, and I felt perfectly at home among them, since I was determined to become a great writer. By this time I had written the first three chapters of The Outsider, starting off with Barbusse, then going on to talk about Sartre and then Wells' Mind at the End of its Tether. Fortunately my reading had been very eclectic; I'd also been lucky in stumbling upon the kind of thing that I needed. I'd admired Nietzsche since I was about 15, and had bound my copy of Thus Spake Zarathustra in soft leather so that I was able to carry it around in my pocket like a bible. The other book that deeply influenced me was the Bhagavad Gita, which I came across through a reference in T.S. Eliot. I found when I was 16, working in the lab at school, that if I sat and meditated for three-quarters of an hour a day, and that if I got up very early in the morning and took a long run and then walked into town to school instead of taking the bus, that I just felt much fresher and happier. I'd always been fascinated by religion, particularly by religions like Buddhism and Taoism. I'd had this desire to know everything, so when I came across a huge volume called The Bible of the World, I borrowed it and read huge chunks of it, and when I found an abridged edition called The Pocket World Bible, I carried that around with me for years. All of this was poured into The Outsider, as well as all my reading about existentialism: I'd discovered Kierkegaard, read Camus' La Peste when I was married, then came across his L'Estranger, which in England is translated as The Outsider. I also been fascinated by Van Gogh for years, and read his letters, and a life of him, and had books with reproductions of his paintings, and was really quite obsessed by him as well as by Beethoven. And George Fox, founder of the Quaker movement. All these Outsider figures were my heroes.

Now, Joy and I went down to Canterbury Cathedral sometime in the spring of 1955. We wandered into a secondhand shop and I came across a book by Victor Gollancz called A Year of Grace, which was a religious anthology. I bought this for a few pence, and thought, ah, Gollancz would probably understand what The Outsider is all about, and so I carefully typed up the first chapter—in fact, an introduction to the book which is no longer there—and also typed out a chunk from the middle of the book, from the chapter about T.E. Lawrence. I sent these off to Gollancz, and to my great surprise and delight, I received a letter back from him saying, this seems to be a very interesting book, we'd like to see it when you've finished it. At that time, my mother suddenly became very ill—her appendix exploded and she had peritonitis and it looked for awhile as if she wouldn't live—so I rushed up to Leicester, but before I went I went into the office of Victor Gollancz in Covent Garden and asked his secretary if I could leave the half of the book that I'd written and typed up, and she said, no, Mr. Gollancz won't look at unfinished manuscripts and I said, look, I may be gone for months, and I finally persuaded her. Fortunately my mother didn't die—she pulled through, after a near death experience in which she felt an angel appeared to her and said, no, it's not your time to die yet. By the time I got back to London I found a letter waiting from Victor Gollancz saying he would definitely publish the book, and he suggested a better title would simply be The Outsider, and, you know, would I get on and finish it. This overjoyed me but at the same time made me terribly nervous; I was sure that he wouldn't like the rest of the book and that it would all fall through. I plodded on; Joy and I came on holiday to Cornwall that August; I felt it wonderful, that sensation of freedom, and that things were changing, that life was becoming interesting and was no longer harrying me, hunting me from pillar to post. I took various jobs during this period, moved into a room in Notting Hill Gate, a battered house that badly needed repairs, and I was in that house in May 1956 when The Outsider finally appeared.

I'd already had some signs that it was likely to be successful; I'd been sent along to be interviewed by some nice journalist, and he immediately went for this whole business about sleeping on Hampstead Heath; I was at a party and met a young Scotsman who said he'd read The Outsider and thought it was a wonderful book; I said, how did you manage to read it, and he said he'd got hold of a proof. His name was James Burns Singer and he was a poet, and he invited me the next day to go with him when he went down to the magazine Encounter to pick up a check, which he then cashed, and he went out on a binge taking me with him. It was the first time I'd seen the Scots' capacity for consuming alcohol. He was a brilliant poet but died a few years later. On Sunday morning May the 26th 1956, Joy was staying over, and we got up at about eight o'clock, hurried down to the corner and bought the two leading Sunday posh newspapers, The Sunday Times and The Observer, and both turned out to have rave reviews of The Outsider. One by Cyril Connelly and the other by Philip Toynbee, both the major reviewers of those papers. Then somebody told me there'd been a review in the Evening Standard the night before; the headline read, "He's a major writer and he's only 24." Success—within hours the phone was ringing nonstop. First my editor from Gollancz saying an awful lot of people wanted my phone number—well I hadn't got a phone, but the people in the basement had, and they agreed to take calls, and they must have quickly regretted it, because all kinds of people rang up: Life magazine rang up wanting to do an interview, television rang up wanting me to appear on TV, and so on, all day long.

And suddenly there I was leading a completely different sort of life, being invited out to lunch with publishers and professors, meeting journalists and well known actors, being invited to parties and the opening of art shows. Now I must confess that in a funny way I did not enjoy all this; I've always been very much a loner. Yeats said in a poem, "How can they know / Truth flourishes where the student's lamp has shone, / And there alone, that have no solitude?" And I'd lost my solitude. My TV appearances made my face well known; there was nonstop publicity. This was partly due to the fact that a man called John Osborne had written a play called Look Back in Anger, which had gone on at the Royal Court a few days before publication of The Outsider. So in the same Sunday papers that hailed The Outsider there were rave reviews of Look Back in Anger. The reason that we made such a literary impact was that since the war there hadn't really been many new writers in England. There'd been Angus Wilson, a writer in the British Museum who'd actually been very sympathetic to me; he'd been the superintendent of the reading room. And there'd been the so-called Red Brick School, the university novelists, Kingsley Amis and Iris Murdoch, but they had not appealed to the general public, whereas Osborne and myself were suddenly in the popular tabloids all the time. Journalists would ring me up and say, what do think of the seams in ladies stockings? Somebody wrote to me asking about my publicity methods, and how did I get so much? I replied that I knew as much about getting publicity as a football knows about scoring goals.

After a few weeks I noticed that the whole thing was beginning to turn sour; that kind of silly publicity really made the serious critics utterly sick. One of the persons I appeared on TV with was a friend called Dan Farson, son of a writer who'd been famous in the thirties, Negley Farson. When Dan applied for a job in television they said, who do you know, and he said, well I know Colin Wilson, and they said, okay, if you can get an interview with him we'll give you the job. So Dan came along to my flat with a camera crew and I was eating when he arrived, and I went on with the interview munching an apple. This was something that everybody noted, and endlessly commented on. It was Dan in a way who really started my downfall: I was down at his father's house in Devon, and Dan was interviewing me for a new magazine called Books and Art, and he was deliberately asking silly questions, things like, do you consider yourself a genius? And I said, I do think it's quite important to believe in yourself; people like T.E. Lawrence who didn't ended by being destroyed by their lack of self belief. It's much better to believe in yourself, even if you're wrong, like Keats' friend Benjamin Robert Hayden who thought he was a great painter and quite definitely was not, or the 19th century poet Bailey, who wrote a giant poem called "Festus" which is appalling rubbish. But having uttered those provisos I said, yes, it's important to believe you have talent and possibly genius—Shakespeare didn't mind talking about his genius in his Sonnets—and Dan, ignoring everything I said, asked, are there any other geniuses in England, and I sort of rose to the bait and said, well there's my friend Bill Hopkins . . . the result was that this appeared in the magazine with the giant headline "Colin Wilson talks about: MY GENIUS" and of course this kind of thing just made the critics grind their teeth. I quickly noticed that the tone of reference to me in the press and changed within a few weeks; I'd been too successful. In Christmas 1956 when the expensive newspapers ran spreads about the best books of the year, no one mentioned The Outsider at all, except for Arthur Koestler, who added a little note on his paragraph: Bubble of the Year: The Outsider, in which a young man discovers that men of genius suffer from weltschmerz, meaning inner torment. That sort of snotty highbrow comment—oh we Europeans have known this for ages—was typical of Koestler. Later he became a friend, but that was typical of the comment being made at the time.

Early the following year, Joy went into hospital with tonsilitis, and I went up to see her. I'd left my bag with my journals in it on the table in the hall at her home, and while I was away her sister Fay came and read the journals. The following weekend Joy went to see her parents; as usual they nagged her nonstop about when were we going to get married. They'd been shocked to discover that she'd broken off her engagement to this fellow who'd gone off to Canada, and did their best to break the whole thing up; her father actually called on me at my lodgings and said, get out of town, Wilson—as if he'd had any right to say that sort of thing. But one day, in February 1957, while we were giving dinner to an old poof called Gerald Hamilton, who was Mr. Norris in Christopher Isherwood's novel Mr. Norris Changes Trains (in America,The Last of Mr. Norris), when suddenly the door burst open and in came Joy's family. Her mother, father, brother Neil, sister Fay, and her father shouted, the game is up, Wilson! It seems that Fay had told them from reading my journals that I was a homosexual and that I had six mistresses. I laughed and said, here's the journal, take it yourself, and he raised a horsewhip and tried to hit me with it; I gave him a push in the chest and he fell down; the mother shouted, how dare you hit an old man and began hitting me with her umbrella; I thought this was so funny I literally doubled up roaring with laughter and fell on the floor, whereupon Joy's mother proceeded to kick me! Anyhow, I managed to get to the phone and rang the police; they turned up in five minutes and said to Joy's parents, how old is she? They said, she's 24. The police said, well if she's 24 she can do what she likes. You'll have to leave this gentleman's flat because, you know, you're not allowed on other people's premises without their permission. Joy's family went off, and then I noticed that Gerald Hamilton had also disappeared. In about ten minutes there was a ring at the doorbell; I went down and it was a reporter and a photographer—obviously Gerald had rushed straight to the telephone and rung up all Fleet Street. I let them in, told them what had happened—thinking that this would be a kind of insurance from Joy's parents ever trying it again. But no sooner had we got rid of them then there were more below . . . so we decided to sneak out the back door and spend the night at a friend's. We then took a train down to Devon and stayed with Negley Farson. Meanwhile the press managed to get wind of where we were; Joy's father handed over my diaries to the Daily Mail, which published extracts without my permission; the Daily Express also wanted to publish chunks and because they were quite harmless, I told Bill Hopkins that he could edit them and give them to them for free. And that's what happened; they did a double page spread on the diaries of Colin Wilson, with a cartoon of me being chased by a woman waving a horsewhip, which was actually appropriate, because Joy's father is a very gentle person who hated the whole thing—Joy takes after him—and her mother was the moving force behind it. We were discovered by the press in Devon; we had to flee once again, to Ireland; we were generally in the papers all over the place . . . Joy by this time hated the press and didn't want anything to do with them. We were really pursued in the same way as poor old Princess Diana.

At this point, Victor Gollancz, my publisher, asked me to see him, and he said, for God's sake, get out of London or you'll never write another book. I took his advice. The man in the next room said he had a cottage in Cornwall which we could have for 30 bob a week—that's about $2.50—and we came down and looked at it, loved it, and we've been in Cornwall ever since. I persisted with my second book, Religion and the Rebel; I wanted to call it The Rebel, but Gollancz felt since my first book had been called The Outsider,, he didn't want to pinch another title of Camus', so he suggested Religion and the Rebel and I reluctantly agreed. When I completed the book I sent it along to Gollancz who was delighted with it, said he thought it was a major book and so on—he would of course, because it was centrally about religion and religious mystics. I turned to this aspect of the Outsider in reaction against all that publicity; it was my own assertion that "Truth flourishes where the student's lamp has shone." But when Religion and the Rebel finally came out in autumn of 1957, the critics were so sick of me that the book was panned viciously. Time magazine came out with an article labelled "Scrambled Egghead." Now strangely enough, it was a relief: I got so sick of having that spotlight beating on me for 18 months that to suddenly be once again in a dark corner brought a marvelous feeling of relaxation. I'd said in The Outsider that the whole point about an Outsider is that he goes his own way; he plods along, and refuses to be diverted by the insiders. So I thought it was incumbent upon me to do precisely that. But I must confess it was pretty hard work. I started to write a book with my two closest friends, Bill Hopkins and Stuart Holroyd, which was about the way that the hero has disappeared in modern literature, and that everything has been cut down to size. What I wanted to know was: why was it only possible to have heroes in comic books, like Superman or Batman, or in popular thrillers like the James Bond novels? Why is impossible for a serious writer to write a novel in which the hero ends by winning? Why are all modern heroes tragic? It really sprang out of something I observed in The Outsider: people in the 19th century, the great Romantics, had moments of marvelous ecstasy, in which they felt that the whole world was wonderful; then, when they woke up the next morning, couldn't remember what they meant by it, and felt that our moments of ecstasy are illusion, and the truth is this awful grim world that ends by killing you off. Hence the enormously high suicide rate in the 19th century among writers, philosophers, painters and musicians.

We'd been living in this little Elizabethan cottage for about two years; we asked our landlord whether he wanted it back again . . . since he couldn't be bothered to reply—a typical romantic poet!—we began looking for somewhere else to live. Or rather Joy did; I was staying at home finishing Ritual in the Dark, and she found a house with a for sale notice, but she said it's much too expensive for us—it's nearly 5,000 pounds, which is about $8,000—and in any case it's far too big and I said, good, lots of room for books. We succeeded in raising the cash because although Religion and the Rebel had been attacked so much it nevertheless sold about 10,000 copies, and that was enough for us to put down on a mortgage. We borrowed the rest, and moved into this house with literally about 20 pounds in the world. The Outsider made a fair amount of money; it had been translated into 16 languages, but then it only brought in about a shilling a copy—about 20 cents; it was obvious we weren't going to become rich on this. So we were and always have been permanently broke, which explains to a large extent why I've written so many books. My parents moved into this house with us but that turned out not to be a success, because my father, who'd always wanted to be a countryman, got terribly bored suddenly being out of work with nothing in particular to do except the things he'd always wanted to do, like going fishing and so on, and he just began to go to pieces and spent much too much time in the pub, until my mother insisted on returning to Leicester, which of course he hated even more. He found freedom demoralizing, but hated going back to the factory, with the result that over a longish period he got cancer and died. For which I've always felt partly responsible.

But fortunately, I've always had lots of ideas for books. There was a great deal that I wanted to say. Ritual in the Dark came out in 1960, and that was fairly successful—it didn't sell as well as The Outsider but it did sell quite well, went into paperback, was published in America, went into paperback there. And I began writing more books along this Outsider theme. I'd done this book called The Age of Defeat (in America The Stature of Man) talking about the disappearance of the hero and the need to find some new kind of basic belief that would enable us to create heroes again; now I went on to do a book called The Strength to Dream, which was a study of the imagination; this was followed by a book called Origins of the Sexual Impulse, a subject which, as I've said earlier, has always fascinated me; and then, Beyond the Outsider. These six volumes I called my "Outsider sequence" but of course the critics didn't relent. Many of them just ignored the books, others slammed them.

In the 1970's, I suppose I began to have a new lease on life when I became interested in the occult and the paranormal. In New York I'd met Norman Mailer who said, you need a good agent, that's your problem, and put me on to his agent, Scott Meredith. He wasn't actually able to do much for me but one thing he did do for which I'm eternally gratefully was to approach me with a commission from Random House to write a book about the occult. And I accepted it simply as a commission, as a way of making some money, without any real belief in the subject at all. To my astonishment, when I began to study the subject I found that I got more and more absorbed; before long, I realized that the paranormal has as secure a foundation as physics or chemistry. The great physicist John Wheeler at one point made a demand for all of the phonies, meaning the people who studied the paranormal, be thrown out of the temple of science. But he had not bothered to read up on the subject, he knew nothing about it, he was talking out of the top of his head. So the paranormal provided me with one more subject to plunge into.

Rain Taxi: You've written philosophy, history, biography, criticism and psychology, in addition to novels and plays. What is the common denominator in all your work?

Wilson: I've always been basically a writer of ideas. Ideas fascinate me. Most of my work has been about the question why are we alive and what are we supposed to do now that we are here? But then you could say that all of my work basically springs out of the idea of The Outsider. We experience certain moments in which we feel life is absolutely wonderful. I've noticed it particularly on holiday. We get that feeling that the world is so fascinating, and you say to yourself, ah no, that's just because you're on holiday. Then you take another look and say no it's not, it really is fascinating. Everything seems to remind you of something else. Consciousness seems to spread out in all directions. And this is the state, you realize, that consciousness should be in all the time—like a pond which, when you throw stones in, ripples all the way across. Instead, consciousness has a sort of quality like a very thick heavy jelly that just will not ripple. Human beings seem to suffer from a kind of tunnel vision, only aware of what is in front of their noses. As Huxley suggested in The Doors of Perception, our senses act as filters to prevent too much information from flooding in. The image I've always used is that of the cart horses I used to see pulling wagons in my childhood, whose eyes were covered in blinkers so they wouldn't become alarmed in the traffic. Now nature for some reason has given us the same kind of blinkers, which means we are forced to see the world through a very narrow little slot. So of course we've developed a very narrow, obsessive left brain consciousness, which is quite unlike the wider more easy going consciousness of animals, as Walt Whitman pointed out. And yet it has always seemed to me there's no point in looking back at the animal?that is what I said in The Outsider. No point in wishing we were in an earlier stage in our evolution; what we have to do is to use this kind of consciousness we have to push on until we suddenly break through to new heights.

I've always been fascinated by the historian Arnold Toynbee, who had described that on a number of occasions, being at some spot where there had been some great historic event, he'd suddenly experienced a clear sense of the event just as if it were happening at that very moment. He described being in the ruined citadel of Mistra in Greece which had been overrun in 1815 and had been empty ever since. He'd suddenly had this tremendously clear sense of the day this actually happened, when the inhabitants were massacred or driven out. But see, Toynbee needed a great deal of historical knowledge to be capable of that kind of insight, so it couldn't really be thought of as a kind of occult faculty of the kind that appears to be possessed by most animals. The wife of the Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid once told me that their dog always knew when her husband was coming back from a long trip; he just sat at the end of the lane several days before he returned, and on one occasion even knew before he himself knew he was coming back. We human beings have got rid of these telepathic faculties. We don't need them. Substituted for them is a kind of narrow intensity, a thoroughly practical sort of vision. But you can see that in the case of Toynbee, that narrow intensity was able to enable him to virtually see the past, to raise consciousness to a new level of intensity. I've always called that Faculty X. And the example I've always given is that of Proust who in Swann's Way describes how his hero, coming in very tired one day, had taken a little cake called a madeleine and dipped it in herb tea, and as he tasted it suddenly experienced a wonderfully ecstatic sense of happiness, which he was able to pin down to the fact that the madeleine brought back his childhood with great clarity—he'd always been offered a madeleine when he came back from a long walk every Sunday by his Aunt Leone. In other words the madeleine made Proust suddenly aware of the reality of his past in the same way that Toynbee became aware of the reality of some historic event. So it has always seemed to me that the next step of human evolution is involved with what I call Faculty X.

Rain Taxi: Are the divisions between genres important to you? Your novels, like Dostoevsky's, tend to be novels of ideas.

Wilson: Like Dostoevsky I am perpetually asking this question: what is human existence all about? But Dostoevsky tended to be more pessimistic than I am; it seems to me that these moments of Faculty X and these moments Maslow calls "peak experiences" suddenly show us that life could become infinitely more interesting if only we could grasp how to do it, using this particular faculty we already possess, a faculty of concentration, of focus. But like Shaw, I've always believed that it's better to put ideas in a more palatable form—in Shaw's case, of course, plays—not simply for the sake of making them go down easier, but because you can say certain things in a novel or a play that just do not come over in a work of philosophy. Crime and Punishment has a power that is possessed by no work of philosophy that has ever been written. Shawalways said that the ideal philosopher is the artist-philosopher. I totally agree with him. Which is why I've always written just as many novels as works of ideas.

Rain Taxi: One of your many out-of-print works is intriguingly titled "Science Fiction as Existentialism." Can you tell us the basics of this unusual equation?

Wilson: That was based upon a piece I delivered as a lecture to some science fiction congress in the 60s. What I said was that H.G. Wells was fascinated by science because he felt that it would provide the great answer to human existence—the same kind of answer that I've always been looking for, except that it seems to me that Wells is a lot more naive; he thought that mere social progress could bring it about. He didn't recognize that what we need is a new kind of consciousness. But science fiction has always followed from H.G. Wells trying to investigate the possibilities of human existence. It is one of the most potentially creative forms of fiction. Someone like Ian Watson, whose work bubbles with ideas, is really carrying on where Dostoevsky left off—which is to say he's writing science fiction as existentialism. His novel The Embedding, which I think is possibly the best SF novel ever written, simply could not have been written 25 years ago and certainly could not have been written in the time of H.G. Wells. It's post Aldous Huxley, post Wittgenstein, post structuralism and Derrida.

Rain Taxi: Much of your work deals with the controversial triad of sex, crime, and the occult. What are the connections between these fields of study?

Wilson: First of all I have to explain my interest in crime. I've always been interested in crime ever since I was a child, when my mother used to read these true detective magazines and my father once brought a book home from work called The Fifty Most Amazing Crimes of the Last 100 Years, which he told us kids not to read- so of course we read it from cover to cover every time they were out of the house. It was this actually that inspired me to write Ritual In The Dark, because most of the articles in it had a picture of the murderer in the beginning of the article, but the article on Jack the Ripper had a huge black question mark, which is what got me fascinated by Jack the Ripper. But I suppose what really interested me about crime and continues to interest me is the fact that it brings with it a sense of seriousness. You may be feeling absolutely bored and fed up and then you read about some crime and suddenly you realize how very lucky you are. And that you're just being utterly spoiled or rather reduced to tunnel vision by a curious narrowness of consciousness.

Let me give you an example of what I mean. Last year, I was flying to New York, and the flight is of course is about seven hours and towards the end of the flight—I had a long trip up from Cornwall and that sort of thing—and I was feeling pretty tired and bored, and I was deliberately trying not to feel tired and bored, thinking, for God's sake, here you are in a perfectly comfortable airplane, to be tired and bored would be a sign of being spoiled. Now it happened at London airport I bought a book called Serial Rapist about a man in Clevelend called Ronny Sheldon who raped about fifty women, and he was caught and at the age of 27 was sentenced to life imprisonment. And thinking about this was enough to cause me to make that mental effort of consciousness, suddenly making consciousness contract, like clenching a fist, which instantly got rid of my sense of boredom and made me feel thoroughly wide awake. With the result that when I landed in New York, driving into New York at midday and realizing it was five o'clock my time, the time when I'm usually getting ready to watch the TV news and drink a glass of wine and eat some smoked salmon, I was able to tell myself, come on, pull yourself together, you're going to behave exactly as if this really was midday and you'd had a good night's sleep. I was able to galvanize my consciousness. And I spent a quite cheerful afternoon in New York and got my dinner in the evening not feeling for a moment that I'd somehow lost five hours. Now that is an example of the value of reading about crime!

Of course the psychology of crime has changed greatly since I wrote an encyclopedia of murder in the late 1950s. Even then I talked about a case in which a man, after watching a program on television called The Sniper,

had gone out with a gun and shot a total stranger through a window. A sort of crime of boredom. And this is what fascinates me above all: that human beings are capable of being bored. Compared to our Cro-Magnon ancestors, we are immensely lucky. Even the poorest person on earth, someone living in some awful slum on the outskirts of Beirut or Mexico City, is nevertheless better off than a caveman who starved and froze throughout the winter. Crime makes it clear that there is something wrong with human consciousness, that it's too narrow. During this century we've seen revolutions in Russia and China, and the hope of their leaders that they have finally created the ideal society—man could be completely happy. In fact, all that they emphasized that Marx's analysis was completely wrong and that human beings need more than a pleasant life in order to be happy. In fact, as Dostoevsky pointed out, we even have a funny kind of basic kind of hunger for suffering. Saints flogged themselves because they felt that somehow they would increase the intensity of consciousness.

Now sex fascinates me for the same kind of reason. As I get older I realize more and more clearly that it is an illusion. I like quoting an American judge in a rape case in which a 13 year old girl had been given a lift by a lorry driver and then taken to some remote place and been raped and strangled; in sentencing this man to death, he'd said the male sexual impulse has a strength which is out of all proportion to any useful purpose that it serves. I certainly noted that during my teens, going around with an absolutely perpetual erection, looking at every pretty girl with longing, imagining what it would be like to take her clothes off and even feeling a stir of desire passing some shop window full of ladies' underwear. I remember when I first had sex at the age of 18 and feeling, is this what I've been tormented about all these years? And then of course the sheer irony of realizing that even though suddenly you feel, oh thank God, I see what an illusion it is, you nevertheless are just as tormented thereafter! I had a scene in one of my three novels about Gerard Sorme which was based on fact. Sorme goes into a ladies' shop to buy his girlfriend a pair of stockings. He's just going to stay the night with her, and he happens to turn around casually standing at the counter. In one of those sort of cubicles there's a woman who's left the door open and she's taking off her dress and he can see at a single glance that in fact she is a middle aged woman, and yet that single glimpse of the dress going over her head gives him a surge of desire like a kick in the stomach. He realizes how absurd this is; he's just going along to spend the night with a pretty teenager, and yet he won't feel nearly the same desire as she takes off her clothes he's now felt spontaneously in a flash for this total stranger. It seems to me there is something very peculiar about this sexual equation; we can see clearly that it's illusion, yet it nevertheless continues to entrap us. And I simply want to know how it does it. It's like wanting to know how a conjurer performs a particular trick.

As for the occult, I was very struck by a comment made by Robert Monroe, the businessman who suddenly discovered he was able to leave his body. He remarked that even out of the body it's possible to experience sexual desire, that a kind of sex can take place between two disembodied persons, but he says the kindof sex that takes place between two disembodied persons is real sex, of which the sex we experience is only a kind of shadow, only a kind of secondhand version. Plato had said very much the same kind of thing.

Rain Taxi:You have books due out this fall that are addressed to younger readers. Have you had to alter your approach when communicating about subjects such as the paranormal with children?

Wilson: They were really written by chance, because I had written a large book on commission about the religious sites of the world for a publisher who specializes in doing books that are visually quite beautiful. When the same publisher approached me and asked me if I'd consider doing the text for some children's books on the paranormal, I said yes. It proved to be a very interesting challenge, but a very irritating one too because the editors continually kept simplifying my stuff and turning it into a kind of Enid Blyton, which infuriates me. Then I'd change it back and we'd have to arrive at some sort of compromise.

Rain Taxi:You've written extensively about prose, poetry, and even music, yet you mention visual art less often—is there any which offers the kind of evidence for human development that you seek?

Wilson: You can see from the piece on Van Gogh in The Outsider and the references to Cezanne and other painters in my work that there was a period in my teens when I was fascinated by the visual arts. Before I went into the RAF I spent all my time borrowing books from the library on painting and on particular painters that I'd admired very much like Van Gogh, El Greco, Cezanne, Michelangelo and Leonardo. When The Outsider came out I became friendly with painters like Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon. And whenever I'm in a foreign city the first thing I do is to make for the nearest art gallery. But on the whole I haven't written as much about visual arts simply because it seems to me that to be a great artist is a kind of natural talent that doesn't require the kind of obsession with ideas that interests me so much. I have known a few painters who have been interested in ideas, but if anything it's weakened their work.

Rain Taxi:The upcoming millennium is giving rise to all sorts of strange notions—is there any evidence for the view that significant global changes will occur at this time?

Wilson: Well, I've been writing a book about UFOs, and people who have experienced abductions have said again and again that they've been warned by these UFO denizens of tremendous and catastrophic changes. I feel, as do these UFO aliens, that man is going to have to pull his socks up tremendously in the course of the next 50 years if he's not to turn his planet into a sort of horrible waste tip. Global warming is undoubtedly going to cause tremendous problems: the melting of the polar ice caps, an increase in all kinds of diseases simply because things like mosquitos will be able to survive more easily in a warmer climate. And above all, of course, the overpopulation. I feel almost guilty sometimes about the kind of planet I'm leaving to my grandchildren.

Rain Taxi:Yet your work is radically optimistic—how do you maintain a positive view of human evolution given the extreme problems that plague humanity?

Wilson: As I said earlier, whenever you catch that glimpse of what consciousness is capable of, you realize that our capacities are far greater than we realize. It seems to me obvious that human beings possess all kinds of powers that we don't even begin to understand. We think about these UFO aliens as apparently possessing extraordinary powers, if the stories of abductees are to be believed, the power to make them do things telepathically and all kinds of things. And yet the truth is almost certain that we ourselves possess such powers if only we recognized it. It always seems to me to be so close, that change in consciousness. As I've said again and again, Maslow found that when he talked to his students about peak experiences they not only remembered peak experiences they had in the past, but they began discussing them among themselves and having peak experiences all the time. It's quite obvious that we could learn to generate peak experiences at will. It's a certain kind of mental attitude that's needed and since mankind has gone through some of these terrible problems over the past two centuries—the Industrial Revolution, the twentieth century with its wars—I feel that nevertheless humankind is beginning to emerge as a rather more mature adult creature than he was. I've often said that if an Elizabethan workman had been transported into the modern world he'd go insane within a matter of weeks. And yet now fairly stupid people can live happily in a modern city and yet cope with its complexity.

Teilhard de Chardin thought that the essence of evolution was what he called complexification. And complexification is happening to us whether we like it or not. I think that humankind has remained very much the same over thousands of years. If you could go back to ancient Rome or Plato's Athens, I don't think you would find that human beings were so very different than the kind you know well today. But I suspect that if you could be transported a couple of hundred years into the future, you would find a quite different kind of human being, assuming of course we learn to cope with the problems and to overcome them. And I've always had a very deep optimism about the human race. I believe, as Shaw did, that the brain will not fail when the will is in earnest. Our main problem at the moment is that we are too lazy and short-sighted to really confront our problems, so that a country like China, for example, refuses to enter into any kind of agreement about releasing CFCs into the atmosphere. America still refuses to do anything about gas guzzling cars. When difficulties force us to face up to these realities, then we shall finally apply our minds to solving them.

Click here to purchase The Outsider at your local independent bookstore

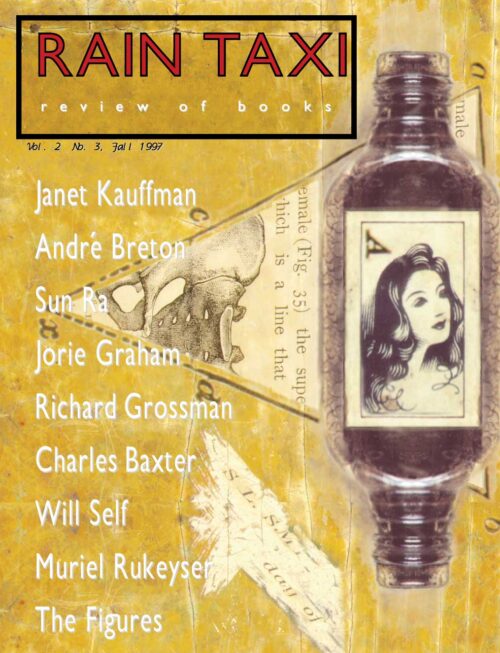

Rain Taxi Print Edition, Vol. 2 No. 4, Winter (#8) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 1997