by Brian Evenson

Carole Maso is the author of four novels--Ghost Dance, The Art Lover, AVA, The American Woman in the Chinese Hat--and a collection of short pieces, Aureole. Her new novel Defiance will be published by Dutton early next year. She is the recipient of a Lannan Literary Fellowship for Fiction, a NEA fellowship, and several other grants.

Maso is able to incorporate different sorts of texts into her novels, from newspaper articles to pieces of art, and can move effortlessly from a fragmented interior monologue (in AVA) to a more confessional narrative (American Woman) or to a series of short pieces that circle around notions of desire (Aureole). In all of her work, desire and the body never seem too distant; perhaps she, more than any other American writer, best exemplifies French theorist Hélène Cixous' idea of ecriture feminine.

In the following interview she speaks, among other things, about her aesthetic, the currents of the literary marketplace, and the conditions facing women who write.

Evenson: In your essay "Rupture, Verge, and Precipice/Precipice, Verge, and Hurt Not," you declare "The future is feminine, for real, this time." Similar claims have been made by others before, but something always seems to happen to push that future under. What difficulties face contemporary women and women writers? What is happening now that makes the future feminine in a way that can't be taken away again?

Maso: I'm not sure similar things have been claimed too many times before in terms of literature--but I do very much believe that one must go over the same moral ground a thousand times before it belongs to one. I think women have been oppressed for so long and in such subtle and complicated ways, in short, so effectively, that it's been and will continue to be a long journey toward even a little light, a place not only in the world, but in the mind we can call our own.

And of course women feel very ambivalent about all this. They are the only oppressed group who for the most part live, sleep with, interact with the ones who are doing the oppressing. Assumptions are made, things are taken for granted. So much so that feminism has become the new "F word" among my students.

I think it's pretty important to try to articulate some of what I attempt in that essay. Even if to some degree it is about assuming a stance of courage or a stance of audacity (or of freedom), until finally real courage takes its place, real audacity. It's important I think, to keep the pressure on such things. For me it's often an interesting place to write out of. The contours of that seemingly open-aired prison. To not emerge already constructed, to not have anything for granted--a book, a chapter, a paragraph, a word.

Sexism is pretty pervasive, I'd say, throughout the publishing scene. Only a college-educated white man can write enormous, sloppy, sometimes unreadable books and be labeled a genius. If a woman attempted such a project she'd be laughed or scorned or ridiculed off the scene. Or worse, ignored. Still, I do think women, embracing the margin, shall write more and more of the most extraordinary texts. I'm a bit amused by the daily celebration of white male mainstream writing. It's an obvious last gasp, last panic, because it's all falling apart finally (is it not nearly 2000?), disappearing. I've never seen so much grandstanding, chest-beating, back patting, smugness. Western civilization (Time magazine, Disney productions, Harvard University) is nervous, as well it should be.

Two of the most innovative American writers of the past were both women: Emily Dickinson and Gertrude Stein. We're only just starting to get that. Much of the best writing being done in this country now is an outgrowth of those impulses I think. I see a union of feminist theorists and women writers. I see overlap between genres and between art forms. It's a very exciting time, really. Some pretty wonderful work is going on in the American avant-garde.

I'd like to say I don't believe feminine sensibility or energy is restricted by any means only to women. Men certainly can have access to it as well. It would be simplistic to believe it could be gender-assigned solely. I might characterize it, though, as a willingness to live in uncertainty, the ability to not be so worried about definition. The embracing of hybrid forms--fluid, porous, strange, bleeding texts. A certain fragility, vulnerability, and also toughness, that women in general tend to be more predisposed to.

Evenson: Much of your work stylistically has similarities to things going on in French and continental literature. There are traces in your work of Beckett, of the nouveau roman. What is your relation to other traditions, particularly French? Do you feel you belong to a tradition of American writers or as working counter to a tradition?

Maso: I certainly do see myself as part of the American tradition that includes Dickinson, Whitman, Melville, Stein, Eliot, Williams, Pound, Stevens, etc. But of course I am madly in love with all great literature and that certainly includes the French writers. You mention the nouveau roman and I love Sarraute, the Robbe-Grillet of Marienbad, the Duras of India Song, Claude Simon. But honestly the French poets have probably been the greatest influence: Apollinaire, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Mallarmé. I love Monique Wittig, to come right up to the French present. Beckett and Woolf have probably had the most direct influence on me. I also adore Bernhard, Frisch, Broch, Jabés, Hölderlin, Bachmann, Calvino, Cortazar, Cha. I'm a bit all over the map. Murasaki, Dante, Shakespeare. Of course, I could go on.

Evenson: In your work, there seems to be always a connection between language and desire, the two intermingling in often unpredictable ways. Can you speak about connection between the two, discuss the way in which you see the two as linked, both in your work and in the larger context?

Maso: This is an incredibly complex issue and I couldn't do justice to it in a form like this, but I have written an essay called "Except Joy" (in Review of Contemporary Fiction, Fall 1998) on the notions of language as heat and light, motion and stillness, a vibrant living thing capable of containing great emotion. Also fluid, shifting, elusive, fugitive, and ultimately outside one's grasp. Shapes the silence and darkness keep taking back. Bodies which make fragile, amorphous, beautiful shapes for a moment and then are gone.

Evenson: Much of your work manages to cross genres. In The Art Lover, for instance, you incorporate visual images with your text, bring in pieces of newspaper articles and so on and in some senses subvert the notions of what the novel as a genre is. What do you see the literary text as being? What is your relation to genre?

Maso: Sometimes I see it as a field, sometimes as a stage, as a screen, as a sky, as a canvas, as a hand, as a heart, as an egg--anything that can be inscribed. What genre it is seems to me something for publishers, bookstore owners, critics to come to terms with, though when I read Stein's novels I'm particularly enchanted by her conviction, "it is easily understood that a novel is everything." And she means it. And so do I.

Evenson: In The Art Lover, you explore the distinction between fiction and reality, and in fact have a section where the fiction is suspended and you talk in what seems to be a nonfictional section about a friend's death. In The American Woman in the Chinese Hat the line between fiction and reality is very thinly drawn, and leads the reader to speculation on to what degree this is biography, to what degree fiction.

Do you make a clean distinction between life and art? Are there boundaries you refuse to cross? What sort of appeals does your fiction make to the reader?

Maso: I am genuinely incapable of telling the difference any longer between my so-called real life and my writing life. There is no clear point for me where one begins and one leaves off. I think the work feeds the choices I make in my life and my life feeds the choices I make in my work. And to one degree or another that has always been the case. Each completely creates the other at this point. It's an odd thing. The creative impulse runs through us all, I think. You don't have to be a writer or an artist to make, re-make, celebrate, relish, transcend, destroy, rehearse, re-imagine, begin again. It's the becoming I love. Whether I'm writing or not, it's the same thing. This extraordinary journey. A rather hopeful impulse finally. For me at any rate.

I think my work, especially The American Woman or Aureole, invites the reader to imagine the sources of the material, what was at stake, what it means to the writer to write the text. All my books are about the creative act to one degree or another and so to me it's perfectly sensible and well within my larger project to deliberately invite this sort of speculation. The seams have shown in one way or another since The Art Lover, and I think this relationship something well worth encouraging in a reader. In this way the reader gets intimations and glimpses into what it meant for someone else, one other human being, to be alive. What it was like to be here, what the creative act entailed. It's a breaking down of the usual boundaries between writer and reader.

I have no desire to prevent such a relationship, nor do I believe it would be possible to prevent, or to control the reader's response. I don't believe in the writer as legislator or God. I have little interest in controlling the reader. It is perhaps what distinguishes me and my work from a more mainstream writer. One needs to live with the consequences of one's work. I love and fear a little the fact that readers respond to Aureole in a way that extends the notion of what a book ordinarily is. The response has been passionate, visceral, and I would say the level of engagement is on a completely different plane than what has been the case for my other books, and I would guess most books. To the degree that Aureole becomes an experience that exists as heat or light, friction, dissolution, as spirit, as body, as a world that overflows the covers of the book, and crosses into a kind of derangement, a kind of urgency, waywardness, need--a pulsing, living, strange thing. A passionate thing. It's an extremely vulnerable position to be in--the potential for ridicule and dismissal by others is enormous, but it also feels great, dangerous, thrilling. For me at any rate. I am willing even when it is difficult, painful, hurtful to live there. I am dealing more directly with this in a new book called Beauty is Convulsive. It's about the life and work of Frida Kahlo, and it's also about me or my work. Through her I get to examine the direct use of one's self (external, internal) to make art, and the cost of that--it's expensive in many ways--and the bravery and stupidity of that, and the necessity, the internal imperatives one works with. I love what the critics have done with her, calling her histrionic, hysterical, self-aggrandizing, shrill, etc., etc., all the usual attacks reserved for women. The book will be the attempt to retrieve a woman from the icon while simultaneously respecting her deliberate playing into that role.

Evenson: Except for the recent Aureole, your books have been novels. What made you decide with Aureole to turn to short pieces?

Maso: The short pieces arose out of necessity. I began these while teaching and directing the creative writing program at Brown. I found my stamina and attention span to be greatly reduced. I need to write every day and so thought this might be a way to continue.

I consider these pieces to be experiments in my narrative and language laboratory. I'm called an "experimental" writer, after all. It's a place to play around with the thousand different relationships between language and desire. A place of infinite possibilities. A reckless place. A novel requires a fairly sophisticated and highly wrought set of rules (even to digress from). It takes me many years to write one, and is highly demanding in its large, architectural requirements. The short pieces, written quickly and with a sort of joyful abandon and daring are a very different kind of space. They are very serious, but in an entirely different way. Finally, though, in the end they are a way to keep my hand honestly in serious exploration while teaching. I relate very much to the Picasso quote "When I don't have red, I use blue." You use what you've got. That's all there is to it. The small pieces make me want to write larger novelistic works and the large ones make me want to write small ones. It's all about desire for me really. The many ways of pleasure.

Evenson: AVA seems to me to be a culmination of many of the impulses found in your other books. It seems as well to break with narrative more than your other work, to establish a space in which narrative is abandoned in favor of other sorts of arrangements.

Maso: I see AVA as a distillation of the formal methods employed in Ghost Dance and The Art Lover. I see the lines of AVA functioning as the separate sections did in the earlier work. The kinds of mysterious, hypnotic, lyric leaps that happen in the first two books become the method of AVA. To me all my work is of a piece. I feel slightly perplexed I must say when I hear AVA is not narrative. I think it just redefines narrative, reformulates it. It's like where Ava says somewhere "and if not the real story, then what the story was for me." I don't think it's such a good idea to assign to old definitions of what narrative is to new work. The worst thing of all, and I've probably already said this, is to emerge already constructed. Somewhere most writers entered a pact, some weird silent agreement was made as to what story is, character, time, all of that. What passes for narrative in most fiction I just find senseless. Literally, I cannot make sense of it. For me, narrative does not reside in these old, artificial notions. Narrative in AVA is refigured; I think that is true.

On a different note I am always looking for the formal structures for emotion. In my forthcoming book Defiance, to convey the rage and hopelessness and sorrow of my narrator's condition it made perfect sense to play with the so-called conventional narrative. It's about a woman imprisoned, sentenced to death (she's murdered two of her students at Harvard). It made a sense to use a kind of tyranny of narrative to embody such a state. Nothing else to my mind would have been quite as effective in rendering this. It was fun on some level, and a bit diabolical to be able to talk about the ludicrous straitjacket of these kinds of narrative conventions by employing them to dramatize the imprisoned, claustrophobic, raging psyche. I was allowed the delicious position of being able to constantly undermine and question the standard narrative stance while utilizing it.

I think too that the book will lay to rest the claims that I can't write a "normal" book and so have opted for a more "alternative" or "experimental" style. At any rate, it's the typical condescension from some of the mainstream I've grown very used to. So little really is allowed there. So much is feared. Well, we get back to the kinds of oppressions and judgments and strictures we began this interview with. I am trying to write myself free. Wish me luck.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

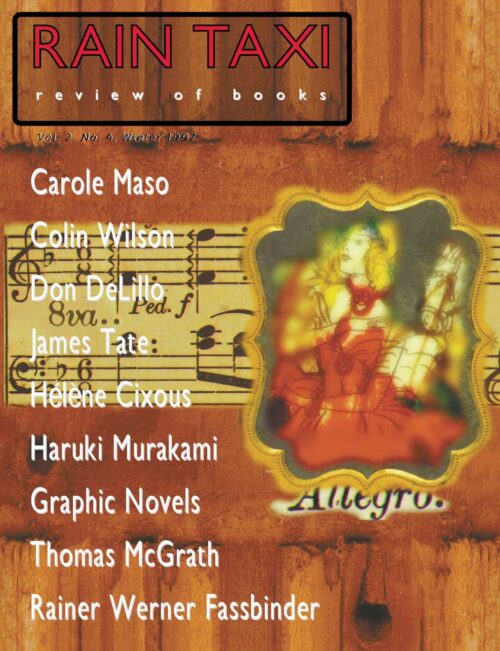

Rain Taxi Print Edition, Vol. 2 No. 4, Winter 1997/1998 (#8) | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 1997/1998