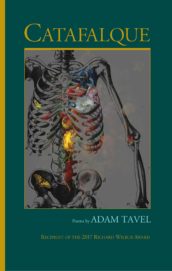

Adam Tavel

Adam Tavel

University of Evansville Press ($15)

by Dana Wilde

I doubt if the judges who awarded the 2017 Richard Wilbur Book Award to Adam Tavel’s Catafalque were thinking about Edgar Allan Poe at the time, but they might have been. For a couple of reasons.

One is the subject matter: Tavel’s poems cover a large range of personal pain. The collection wends in and out of anecdotes of awkward instants—including a boy’s ambivalent recollections of his grandmother (“My Grandmother’s Chores”), childhood illnesses (“Eazy-E’s Abandoned Letter to His Seven Children from Cedars Sinai Medical Center”), ruminations on literary history (“Cora Taylor’s Letter to Joseph Conrad Following the Death of Her Lover Stephen Crane”), the weird sudden collapse of a classmate (“Faint Assembly”) and other adolescent humiliations—and explicit elegies, many of them marked by religious allusions and the continual presence of death. (A catafalque is a platform for a coffin.) Poe’s subject matter was not autobiographical in the sense we understand it now, but he was preoccupied by weird manifestations of physical and psychic pain, and Tavel makes that preoccupation personal.

Another connection to Poe is that practically every line in this collection is anchored to a fairly heavy rhythmic beat, usually iambic. For example, “At the County Morgue,” in its entirety, reads: “Before they fold the cover back you know.” This is Poe-like subject matter in unmistakable iambic pentameter.

Tavel uses rhythmic choices such as this to effect a declamatory voice, sometimes almost stentorian and often forged from postmodernly peculiar turns of phrase. Take the opening lines of “Jogging Weather”: “Your sonnets heaped atop the dead must end / the turkey buzzards squawk, or so I hear / them say.” These lines are straight-up iambic until “or so I hear”—Tavel has a good ear for when to vary the metronome while maintaining the declamatory tone, in part because he also runs heavy on alliterations and assonances, a sign of what Poe called (in The Rationale of Verse) the music of poetry as distinct from “versification.”

Tavel’s poetry would make a good vehicle to demonstrate Poe’s observation that the rules of prosody are artificial overlays which have little to do with poetry and its effects. Terms such as “iambic” are scansion descriptors first used to analyze ancient Greek and Latin, and by Poe’s time were applied in Procrustean ways to English even though they often inaccurately describe what they’re describing. Tavel’s poems lean so hard on iambic rhythms that they could provide a critic with clear material to show how the American version of high poetic diction does exactly what Poe reveals prosodic analysis doesn’t.

Not that this is a particularly pressing issue any more, because prosodic analysis is by and large a vanished activity in English departments. A thorough, readable study of postwar American prosody has been lacking for decades, but Adam Tavel’s clear insistence on the music of meters forces us to give some thought to the idea that poetry, even amid strong tendencies to speech rhythms, is still an analyzable form of music. It’s a welcome change.