Andrew Ervin

Andrew Ervin

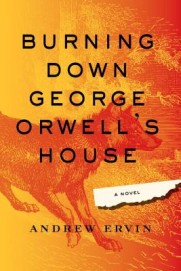

Soho Press ($25.95)

by Tina Karelson

Andrew Ervin’s Burning Down George Orwell’s House, a novel of creative-class angst, comes to readers ingeniously wrapped in a travelogue. Ray Welter, a marketing savant at a Chicago ad agency, has lost his marriage and his peace of mind to cynicism and alcohol. Obsessed since college with George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Ray flees to Barnhill, the house where Orwell wrote the book, on the remote Scottish island of Jura. There, Ray wallows in self-pity, single-malt whisky, and local color.

Two long chapters in flashback, alternating with chapters set on Jura, outline Ray’s life and career. Inspired by “the Orwellian nature of social media,” Ray creates a pseudo-environmental movement that actually increases the sales of gas-guzzling sport-utility vehicles. Despite, or perhaps because of, his success, Ray becomes disillusioned, reaching a breaking point when his father dies in a factory explosion. He impresses his company by not attending the funeral, but “what the board took for stoic dedication to the craft of strategic branding, Ray knew to be abject fear.”

On Jura, Ray is the subject of gossip and even hostility; someone or something regularly leaves an animal carcass on his doorstep. For the first two weeks, he descends into a nearly animalistic state himself. As he ventures out and begins to explore the island in his inadequate footwear—he ignores the islanders’ advice about buying wellies—he rebuilds connections to physical work and the natural world. His way out of despair will not, however, be as simple as breathing fresh air and helping a neighbor build a fence.

While Ray’s extraordinary self-absorption makes him barely conscious of other people, Ervin’s cast of secondary characters is varied and lively. Helen, Ray’s estranged wife, is “the smartest person who had ever been nice to him.” Ray’s boorish but clever boss, Bud, spins endless variations on his name, from Man Ray to “Ray-son d’être.” Farkas, the genial fellow in charge of Jura’s distillery, sincerely believes himself to be a werewolf. Whisky itself becomes another character, each taste described in loving terms, “like caramel and wood smoke and moonlight glowing on a winning lottery ticket.”

Burning Down George Orwell’s House raises genuine questions about ambition, change, and freedom. The novel never offers Ray or the reader simplistic answers to life’s questions, and it tempers Ray’s misery with comic moments. By the end, although Ray finds it impossible to be truly off the grid, he does find his way back to himself. Readers will enjoy going with him on that journey.