Kevin Grange

Kevin Grange

University of Nebraska Press ($19.95)

by Barb Teed

“I had to wonder—why are the most beautiful places in the world also the most dangerous?”

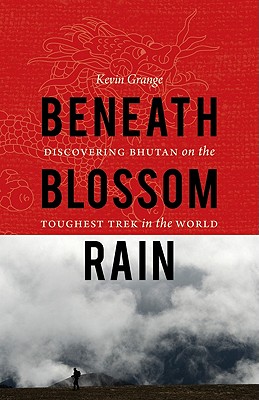

The lure of legends and the allure of mountains have possessed the human race for eons. Kevin Grange’s remarkable debut, Beneath Blossom Rain: Discovering Bhutan on the Toughest Trek in the World, merges the myth of the Yeti and the tangible Himalayan mountains into a tension-filled journey through Bhutan, Land of the Thunder Dragon. Grange transports readers on his 216-mile, twenty-four-day Snowman Trek—named for the often sighted, never confirmed, Abominable Snowman. His task, and that of his nine-member trekking party, is to stay alive and complete their journey on what many deem the planet’s toughest trek. “Historically, fewer than 120 people attempt the trek each year, and of those, less than 50 percent finish,” writes Grange.

Surrounded by superstition, trail ghosts, 369 varieties of orchids, and the mystic location of Shangri-La, Grange seeks understanding of his life and the meaning of blossom rain, or metokchharp. Blossom rain, explains Grange, is steeped in Tibetan and Bhutanese folklore. He describes it as that moment of rainbow light when it is rainy and sunny at the same time. When this happens, it’s considered very favorable. “I understood that the moment of blossom rain is auspicious, but I wanted to know why and, more important, what it meant. I had a hunch it would help me on my own journey.”

On the twenty-fourth day of the ninth month in the year of the Fire Pig, or September 24, 2007, he begins his excursion with the Canadian Himalayan Expedition and guide. Grange knows the Snowman Trek is going to be tough—day two, for example, is 13.6 miles with a 2,250-foot-elevation gain, nearly twice the suggested rate for proper acclimatization. His tour group includes sixteen people, thirty horses, twelve tents, and a portable chamber to treat severe altitude sickness. “Everybody cries at some point on the Snowman Trek,” his trail mate informs him.

Constantly facing altitude sickness and inhospitable environments, Grange gradually becomes enamored by fragile plantation, rare animals, and the continual warmth and contradictions of the Bhutanese people. For example, Grange commits to making the trek technology free in order to experience the Zen-like atmosphere. He is amazed when, during a puja ceremony performed by Buddha monks, a priest takes a ringing cell phone from underneath his robe. Similarly, prayer flags Grange describes as the “sacred speed bumps” “on the highway of trails throughout the Himalayas” catch the wind and romance of the Snowman Trek but at the same time conflict with the detailed phallus symbols painted on houses. The pictograms honor not fertility but one of Bhutan’s most famous saints, the Divine Madman.

Grange’s earlier attempt in 2004 to finish Bhutan’s Jhomolhari Trek failed when altitude sickness forced his abandonment. Internal doubt about achieving the Snowman Trek compels examination and conversation within Grange interwoven throughout the book:

But loudest and worst of all was the voice inside my head—my inner critic—that old familiar foe.You have insomnia, it said. No I don’t, I replied. It’s the first sign of altitude sickness. I’m just adjusting. You never should’ve come. Yes I should have. You’re going to quit, waste all your money, and look stupid. No, I won’t. Yes, you will. No! Yes! No!

His search for self follows Grange into Bhutan, a nation promoting Gross National Happiness, and he finds the isolation of the Himalayans strangely comforting: “I’d felt far more remote on a crowded anonymous street in New York City than I ever did on the Snowman Trek.”

Grange successfully blends trail terror with trail humor. Snow camels, or yaks, are traded for horses at higher elevations and present a new set of challenges for the group. “How would I describe the arrival of the yaks? They were like thirty, half-ton first-graders with sharp horns on a field trip.” The hazards of the toilet tent he presents as akin to a lethal combination of Sartre’s No Exit and Milton’s Paradise Lost. “Could the toilet tent be the reason only 50 percent of people finish the Snowman?” he wonders.

Bhutan history and mountaineering lore weave throughout Grange’s writing with a series of flashbacks to early years growing up in New Hampshire. His journalism background crafts a well-researched read, and he effortlessly spins Bhutan’s environment and landscape into screen-worthy images. In the vein of Aron Ralston’s Between a Rock and a Hard Place and the film 127 Hours, the book shows why extreme adventuring is so difficult to resist. Readers will forgive Grange’s occasional slips into clichéd slang and will find him, and Beneath Blossom Rain, charming and witty.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Summer 2011 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2011