by Rone Shavers

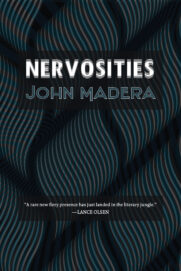

If the subaltern could speak, John Madera’s Nervosities (Anti-Oedipus Press, $18.95) would highlight exactly what they’d say. Every work in this collection of experimental short fiction mines and limns the interior struggle of someone living at odds with their perceived or all-too-present reality, characters that veer from existential crisis to socioeconomic crisis to literal crisis to physical crisis and all the way back around again. And yet, who among us can really blame them? In the new fresh hell of our current political administration, where every day starts with What now? and ends with WTF, Nervosities strikes a chord because it happens to be as timely and necessary as it is prescient. Madera is a prolific, prodigious writer and literary critic, so the reader can readily expect nothing less than a careful detailing of our current, almost constant societal and political breakdown.

If the subaltern could speak, John Madera’s Nervosities (Anti-Oedipus Press, $18.95) would highlight exactly what they’d say. Every work in this collection of experimental short fiction mines and limns the interior struggle of someone living at odds with their perceived or all-too-present reality, characters that veer from existential crisis to socioeconomic crisis to literal crisis to physical crisis and all the way back around again. And yet, who among us can really blame them? In the new fresh hell of our current political administration, where every day starts with What now? and ends with WTF, Nervosities strikes a chord because it happens to be as timely and necessary as it is prescient. Madera is a prolific, prodigious writer and literary critic, so the reader can readily expect nothing less than a careful detailing of our current, almost constant societal and political breakdown.

John Madera manages and edits Big Other, an online journal that specializes in showcasing innovative and experimental creative work. His poetry and prose have appeared in Conjunctions, Contrapuntos, Hobart, and Salt Hill, and his criticism has been published in American Book Review, Bookforum, The Brooklyn Rail, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, and Rain Taxi. What follows is an interview conducted the old-fashioned way: by correspondence.

Rone Shavers: How would you define “experimental” writing, and do you consider your work to be experimental?

John Madera: Defining can be a kind of confining, especially with a term like “experimental,” where any kind of gesture toward exactitude—in this case about its fundamental nature, range, scope, meaning, etc.—will betray any number of holes in the so-called whole. So as this slippery thing falls out of our hands—when was it ever in our hands?—this is getting out of hand!—let’s observe it less as what it is and more as what it does.

Another way of answering this question is to continue the play of the formlessness of forms—forms themselves potentialities, things whose thingness comprises deformation, transformation, and conformation (this last term I’m using as a chemist might)—by playing with the form of the interview qua interview, a possible adventurous endeavor where I might answer every question with a question, echoing playful texts like Padgett Powell’s The Interrogative Mood: A Novel? and William Walsh’s Questionstruck, both of which are entirely composed of sentences end-stopped by question marks. We could also—as Lance Olsen does in one section of his marvelous prose object Always Crashing in the Same Car: A Novel After David Bowie—publish only the answers to the questions, which would foreground the instability inherent within questions, absence in this case making the mind further wander.

Here’s another way of answering by not answering, at least not with any kind of exactitude: you, the you who might be reading this, might recall yourself back to a biology class where you were charged to perform a dissection of a frog, which, its etherized state notwithstanding, nevertheless revolted you, this experiment ultimately a palpable model of biological studies, including vertebrate anatomy, evolutionary adaptations, and physiology. However new the experience might have been for you, however enlightening the results had been for you, the experiment ultimately had likely not resulted in any new findings; that is, your experiment likely hadn’t contributed anything toward broadening scientific knowledge in a general sense. The results are predetermined in such an experiment, in other words. But then there are scientific experiments where the results are not only not predetermined but have arguably changed our understanding of reality. All to say, there’s a range of experimentation, which you might say begins with the “historical,” which arguably one needs to absorb or reenact in some form or another before proceeding toward the opposite end of that range: an end that knows no limit, an end that is an endless beginning: the realm of the radical imagination.

So as in science, there’s a range of what might be called “experimental” in art. Alas, most of what’s published is at the bottom of that range, experiments like the abovementioned dissection, where the results just foreground already known conclusions, where what is written is just another cold, bloodless corpse destined for the garbage can: putrid refuse as opposed to fruitful refusal. Fortunately, however, there are writers who have and are experimenting at the highest levels of that range, whose works make the impossible possible, works that take the givens that everyone else who works with language uses only to problematize those givens, ultimately offering something that reveals previously hidden “knowledge,” further potentialities, more questions—works, moreover, that deterritorialize the stratifications of the state, the market, the temple, of imperialism, consumerism, fundamentalism.

Great filmmaker Robert Bresson said, “Make visible what, without you, might perhaps never have been seen.” And I’ll add: make thinkable, what, without you, might perhaps never have been thought; make readable what, without you, might perhaps never have been read; make feelable what, without you, might perhaps never have been felt; make audible what, without you, might perhaps never have been heard; make touchable what, without you, might perhaps never have been touched; make tasteable what, without you, might perhaps never have been tasted; make smell-able what, without you, might perhaps never have been smelled.

RS: Do you consider yourself to be a “difficult” writer? What does literary difficulty mean to you?

JM: Easy makes me queasy: if the opposite of “difficult” is “easy,” would any self-respecting writer, not to mention any other person—whatever that is—want to be easy? Easy is synonymous with obedient, conciliatory, placating, going-along-to-get-along. The easy person is a people-pleaser who makes, says, or does things everybody likes. The easy person does everything they can to fit in, always asks for permission, steps and fetches, and the like.

To make something vitally unusual requires that one be “difficult,” requires an indominable obstinacy along with total vulnerability, a knowing steadfastness in the face of great unknowing, likely misunderstanding, possible censure, ridicule, ostracization, etc.; it requires rugged determination and patience that may on the surface look like foolhardiness or intransigence in the face of so-called reality, but which is really heartful pluck, whimsical vim, and empathetic elasticity.

That said, it’s not a willful difficulty that genuinely adventurous, generously subversive writers aim for; they don’t deliberately and mean-spiritedly set up obstacles for the unsuspecting reader to overcome, the act of which strikes me as a kind of sadism. The aim—or, better to say, the process such writers live within—is one where they set up difficulties for themselves, organize challenges that compel them to go beyond their current abilities, to go beyond, moreover, what society’s planners, the disciplinarians, the authorities, the professional managers, the haters, the naysayers, etc., say is their place, which is “nowhere” in the worst senses of the word.

All to say, difficulty is a pleasure, the pleasure of getting lost, of stumbling around in the darkness of the unknown, of the impossible.

RS: How would you describe your ideal reader?

JM: We live in a society where most people don’t read, the act not in its most substantial, life- and love-affirming sense of the word, anyway, a society where reading, which is to say, immersive reading, is such a rare act as to be something sacred, miraculous.

So, in a way, my ideal audience in this a-literary wasteland would be people who might be incredibly resistant if not outright antagonistic toward what I’ve written, where the experience of reading the fictions I’ve composed starts after they’ve closed the book. My desire in this respect is something like great filmmaker Jacques Tati’s wanting “the film to start when you leave the auditorium.” That said, I do see myself working within a continuum where even if my writing goes largely unread, it still contributes to what is possible in a reading experience. Every so often—and I say this with profound gratitude—I receive a discerning response to something I’ve written by people who are not only discerning readers but extraordinary writers in their own right, the experience of which serves, albeit temporarily, as a kind of affirmation that my work is necessary.

RS: Several of the stories in Nervosities, like “An Incommodious Vehicle of Recirculation,” are written without any paragraph breaks, making them similar in style to the works of writers such as Thomas Bernhard. What extra layer of meaning is added to the work when writing without period or paragraph breaks, as opposed to a more conventional, “reader-friendly” style?

JM: I love Bernhard, though I hadn’t read anything by him by or during the time I was writing Nervosities. The story “An Incommodious Vehicle of Recirculation” takes its structure, its circular form, from Finnegans Wake, and its title is a play off a phrase from same. Circularity, mortality, love, travel, and language figure as major themes in the story for a character who despises the “general lack of precision, the same kind of attitude responsible for people using the same word for so many things, stretching its meaning toward a multiplicity of meanings, but at the expense of making the word less meaningful, less full of meaning, where more actually meant less.” [182] I’d say, besides James Joyce, if there’s a primary influence on the appearance of long paragraphs in my writing, it’s Henry James, whose circumambulatory sentences tend to delightfully sprawl. Another possible influence in this regard is William H. Gass’s various extrapolations on sentences, particularly “The Architecture of the Sentence.” Gass’s own sentences about Henry James’s sentences are as attentive to scaffolding, sonorities, etc., as the James sentences he’s rigorously and lyrically examining.

As for “reader-friendly” style, what the so-called mainstream mainly shovels out are “gripping,” “relatable,” ultimately timid texts that titillate, works that intentionally confuse melodrama for deep feeling, or that flatter the reader’s ego, lure them into thinking they’re smarter than they actually are, and more besides. Thinking about such empty seductions, this quote from John Barth comes to mind: “In art, as in lovemaking, heartfelt ineptitude has its appeal and so does heartless skill, but what you want is passionate virtuosity.” The descriptor “gripping” should be an alarming one, should warn us that the text is something like a raptor that might capture you in its claws and wrench you apart piece by piece. But “violence” is missing from such texts, especially what you might call “generative violence.” They don’t, to paraphrase Dickinson, make me feel as if the top of my head were taken off. They aren’t, to paraphrase Kafka, axes to chop up the frozen sea within us. They don’t, to paraphrase Evenson, worm around inside our heads. Whatever violence those “gripping” texts have is the violence of the state, the status quo, the addictive whatever. Their grip is the grip of the bully, the police, the spectacle, the prison, the church, the corporation, etc. Moreover, those “gripping” texts are what Lyn Hejinian, in “The Rejection of Closure,” calls “closed texts” (which only allow for a circumscribed interpretation) in contrast to “open texts,” where “all the elements of the work are maximally excited” and invite multiple readings and interpretations.

In short, I don’t want to read a “gripping” book. I want to read books that beautifully, provocatively, mysteriously elude my grasp.

RS: Most of your stories, paragraphs, and even sentences are demonstrably longer than what many readers are accustomed to encountering. What intellectual point or aesthetic effect do you think you achieve by writing at such length?

JM: Long, compared to what? Long, yes, compared to the so-called hot take, the snippy snippet, the snarky comment, the rushed judgment. Long when it doesn’t correspond to the dictates of the attention deficit society, the TL;DR society, a society long conditioned by educational systems designed to dumb us down, government propaganda designed to make us pliant and obedient, and corporate media designed to keep us amusing ourselves to debt and death.

In any case, I agree with Viktor Shklovsky, who in “Art as Technique” wrote: “The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.” I think that’s one of the many things a carefully constructed “long” sentence does: it prolongs perception, the act or event of which, unless one is vigilant, one rarely enacts or experiences, to one’s own detriment, not to mention the detriment of one’s community and beyond.

RS: In the story “Reflections of a Walking Ruin,” you make mention of “discordia concors,” something perhaps best defined as “unity gained by combining disparate or conflicting elements.” The idea of harmonious discord could also very well define the overall the aesthetic style of this collection. Do you think discordia concors reinforces or subverts our current literary landscape?

JM: The discordia concors as it operates in “Reflections of a Walking Ruin” might be compared to the conception of the “Third Space,” a liberatory continuum formulated through language where each actor is necessarily a hybrid, a dissolve of borders between identities, histories, and other stratifications. Sentential convolutions and physical perambulations intertwine in “Reflections of a Walking Ruin” to form a narrative in which speculations on the nature of meaning, the act of translation, the question of representation, the logic of the inventory, and the formation of character (artificial and otherwise) act to displace comforting notions of identity and plurality, not to mention space and time. It’s a subversive space, in other words, that will, with any luck, alter actual spaces in real time, similar to the ways objects are willed into existence by the force of the imagination in Borges’s “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.” Moreover, I think of the discordia concors as a kind of utopic space, an affirmative space, an actualizing of the “impossible,” something like Foucault’s conception of “heterotopia,” a transformative, liberatory space, where the seemingly illusory is made real.

RS: In several stories, you mention “thinking about thinking”—what’s sometimes referred to as meta-cognition. By doing so you hint at a character’s deep(er) interior life that the reader is only partially privy to, which makes me wonder: Given that the reader is denied access to the entirety of your characters’ mental lives—we only know what the narrative, or better still, what the characters often choose to tell us—do you think that literature is still the best medium for conveying our interior lives and thoughts? Or, to go one step further, do you think literature is still a socially useful way to connect?

JM: What might be happening in those stories is the intimation that however much “access” a writer might give to a character’s interiority, said access will always only and necessarily be limited. I would argue that most people aren’t aware of the goings on of their own mind, let alone any fictional characters’ “minds,” which, of course, leads to all kinds of trouble and misery.

Literature is just one among many ways to convey interiority, just one of among many ways to foster connection. Such conveyance and connection require a “diversity of tactics,” to employ a term used in vital forms of solidaristic activism.

RS: Many of your titles are thematic; they don’t directly allude to the events or situations within the story. Why is that?

JM: I’m no Heideggerian, but I do agree with the philosopher’s argument that the relation between subject and object, mind and body, part and whole, etc., is ambiguous at best. Here I recall Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” where so-called subject and so-called object reverse positions, which I’d like to imagine was inspired after a reading of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s journals, where he wrote, “What you look hard at seems to look hard at you.”

Seems to me most writers of prose don’t give much thought to the titles of their stories, essays, and books, whatever they eventually use seemingly slapped on it; the titles are, at best, merely indexical or decorative. It’s a lost opportunity, really. Titles can be used to circumvent and otherwise subvert what follows.

RS: Most of the characters in Nervosities seem to be caught in the throes of an existential crisis—they’re searching and striving for a sense of meaning that’s gone missing from their lives. Are you making a larger statement about this particular moment in the world? Is your work trying to capture the essence of our current human condition?

JM: In a way, anyone attentive to the order and disorder of things is in some kind of existential crisis—unless they have, through enormous discipline, liberated themselves from the traps of hope and fear; have gone beyond the unquestioning acceptance of so-called reality, of the so-called reliability of our perceptions, of the seeming solidity of objects, not to mention of time and place.

As for essences, I don’t think my writing captures the essence of the human condition, because I don’t think there are essences, not of things, ideas, or entities, all of which are socially constructed, and therefore unstable, even largely imaginary. And even if essences did exist, the human is a multiplicity, a multi-variegated thing that invariably eludes capture. So let us observe this multiplicity as a worlding, of words, images, ideas, of differences as opposed to identities, of appearances that are also disappearances and vice versa.

RS: Many of your characters are stuck in a maze of meandering thoughts, while also constantly made aware of the presence and absence of physical bodies. Please speak about these aspects in Nervosities.

JM: Like so many of us, some of these characters sometimes fall prey to the false notion that there is some kind of separation between mind and body, this illusion of asynchrony, on the one hand, opening up the possibility of seeing how much of the goings-on of consciousness is actually made up, the realization of which can be quite liberating, and, on the other hand, potentially reinforce the false idea that some kind of tangible separation of body and mind is already the case or that it’s even a possibility.

RS: The importance of words—both the power of words and the necessity of being precise with one’s words—is highlighted in many of the stories in Nervosities. It’s perhaps best articulated in “Anatomy of a Ruined Wingspan,” where you write, “We love to name names, and by ‘we’ I mean, those of us who take pleasure in knowing the names of things, naming synonymous, we think, with knowledge, yes, but also with authority and ownership.” There’s a lot to unpack in that line (especially in terms of the story’s subject), but I simply want to ask if you can speak about why your characters think a misnomer, a generality, or a cliché is enough to trigger an existential or societal collapse. Do you hold the same belief?

JM: Looking at history, I can sadly attest to the fact that misnomers, generalities, and clichés can, do, and will have devastating consequences on society.

In “Anatomy of a Ruined Wingspan,” a tragic accident sends the narrator into a spiral of doubt, of identity, of his very sense of reality, indicated largely by his inserting much of what is said, either by himself or others, in scare quotes, the scariness of it made scarier by his verbalization of the punctuation marks. This tendency of the character may seem extreme, but what it does is textually foreground a certain kind of uncertainty of language, even and maybe especially at its most precise.

As for beliefs, I don’t think characters have any, not in the way we think of us having beliefs. As for whatever it is that these characters hold that we might call “beliefs,” I’d say, no, I don’t hold the same beliefs of any of my characters. I’m not even sure if they are or even were “my” characters.

That said, while I do believe that language can be and maybe always is a kind of subterfuge, an apparatus at several removes from “suchness,” “isness,” and “thereness”; a sedimentation of linguistic and cultural conditions; it is also a mechanism for liberation and awakening—as much a portal as it is a tool as it is a weapon as it is a force as it is an environment.

RS: Who are your literary influences?

JM: Here are some of the literary influences on the writing of Nervosities: John Ashbery’s elliptical collages, John Barth’s ingenious disruptions of genre, Joseph Conrad’s liquid lyricism, Robert Coover’s unruly mythmaking, e. e. cummings’s visual innovations, Samuel R. Delany’s subversive fabulism, Emily Dickinson’s “slant” syntax, Don DeLillo’s steely awareness, Stanley Elkin’s heady, circumlocutory descriptions, William Faulkner’s innovative temporal structures, Leon Forrest’s inventive fusions of myth and history, William Gaddis’s virtuosic satires, William H. Gass’s sentential cathedrals, John Hawkes’s visceral phantasmagorias, Henry James’s rigorous, relentless precision, James Joyce’s adventurous structural and syntactical play, Ursula K. Le Guin’s anarchic sensibilities, Herman Melville capacious seeming-longueurs, Marianne Moore’s allusive perspective shifts, Thomas Pynchon’s wild, nonlinear tale-spinnings, William Shakespeare’s everything, Wallace Stevens’s philosophical intro- and extrospection, and Virginia Woolf’s luminous lyricism.

RS: What about your intellectual and/or theoretical influences?

JM: Great minds think unlike. That is, many ideas, etc., have inspired me in my processes of being and becoming, like Gaston Bachelard’s phenomenology of the poetic image, Étienne Balibar via Spinoza’s concept of the transindividual, Roland Barthes’s palping pleasures of the text, Jean Baudrillard’s icy formulation of the hyperreal, Judith Butler’s expositions on the constructedness of gender, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s theorization of the rhizome, Jacques Derrida’s explosive deconstructions, Frantz Fanon’s diagnoses of the psychopathologies of colonization, Michel Foucault’s taxonomies of power, Édouard Glissant’s formulation of opacity, Stuart Hall’s defining race as floating signifier, Donna Haraway’s attacks on anthropocentrism, Friedrich Nietzsche’s perspectivism, Peter Sloterdijk’s atmospheric ontologies, and much more besides.

My intellectual and theoretical influences would have to also include a host of artists working in other genres, each for whom the worn-out phrase “less is more” is at the very least a laugh: visual artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Mark Bradford, and Pepón Osorio; musical artists like Anthony Braxton, John Coltrane, and Rahsaan Roland Kirk; filmmakers like Peter Greenaway, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Wong Kar-Wai. The list is endless, really.

Engaging the work of all of the above is all part of the continuum of study, practice, and performance that I daily create for myself, a continuum that’s also a kind of destitution, a fugitivity, an exile, an ungovernability, a vital continuum within a web of poetic relations, all of which is under near-constant threat and attack, alas.

RS: What do you want people to take away after reading this collection?

JM: Ultimately, my greatest hope is that as someone is reading or has finished reading Nervosities, they are inspired to make something: make art, make love, make out, make up, make space, make time, make room.

RS: Do you have any final thoughts to share?

JM: Deepest gratitude to you, Rone, for such an expansive reading of Nervosities and for your astute questions about it and beyond. Also, deep admiration for your own writing. Silverfish is a marvelous book, to say the least. Bravo!

As for final thoughts, how about my manifesto for living a radically imaginative life? (There’s some repetition below but some things bear repeating. Some things bear repeating. Some things bare repeating. Some bears repeat things. Bare things repeat some. Etc.) Here it is:

Be the strange you wish to see in the world.

Make, that is, create, form, arrange, enact, and/or perform, a living.

Make more than you consume.

Make study, practice, and sharing/performance your daily continuum.

Keep lighting the good light.

Stand your underground.

Remember: There is no absolute being, only resolute becoming.

Take the path of most resistance as often as you can.

Get lost.

Work outside of and against the state.

Say nay to the naysayers.

Do something every day for someone else.

Honestly face reality, which means acknowledging, properly addressing, etc., the good along with the bad, and everything in between, a lot if not all of which is always mutable.

Acknowledge, celebrate, and express gratitude for all the positive things that are happening for you, your family, friends, colleagues, etc.

Ask for help when you need it.

Daily do at least one thing you love, that brings you joy, that turns you on, etc.

Daily do at least one thing that brings you closer to a creative goal.

Daily do at least one thing that brings you closer to a vocational goal.

Eat healthily and heartily.

Exercise and exorcise.

Get a good night’s sleep.

Have I mentioned singing and dancing? Have I mentioned cooking? Have I mentioned reading?

Have I mentioned taking a bath? Have I mentioned getting lost? Have I mentioned going wild?

In any case, I’ve found these practices to be helpful through even the best of times; in fact, they help to prolong them. That said, the list above is not meant to be a substitute for any therapeutic practice, regimen, etc.

Be vulnerable and uninhibited. That is, endeavor to open yourself to the life-affirming possibilities of the radical imagination against death cult capitalism’s command for us to police, imprison, and kill our dreams, visions, etc., not to mention our lives and the lives of others.

Do everything you can to free yourselves from convention, from received thinking in all its forms, moreover from the society of the spectacle, the society of surveillance, discipline, and control.

Speak the unspeakable. Write the unwriteable.

Feeling helpless? Ask for help. Help others. Do what you can do. Whatever you can do is enough. If you can’t do anything, do that. Whatever you do, don’t beat yourself up.

Fallow periods are sometimes necessary. Respect it, if that’s what it is. That is, do everything you can to plow and till the field even as you necessarily leave it unseeded. But how do you know if this, whatever it is, is such a period? Hard to say, but here are some things to remember as you figure it out or not: Art is food. That is, it’s absolutely necessary, not some decorative frill or gratuitous thrill. You’re a farmer. Get to work. Also, eat and eat well, lustily, and without apology. I’m still talking about art but do this with your other meals, too. Moreover, be honest. Be fearless. Go crazy. Disobey. Do something every day for someone else. This could be a meal. Express gratitude for what you have, even if it’s “only” for the vision of a future feast.

The programmed homogeneity of social media, which is just a node of corporate media’s manufactory of consent and dissent, makes it enormously difficult but not impossible to discover or re-engage with worthy artists and other revolutionaries, doggedly working in the margins. So, seek out and otherwise engage such people’s work as part of your daily creative practice. Regularly publicly share your findings as a way of building community, because it in some way micropolitically circumvents the abovementioned homogeneity, conformity, and servility.

Champion the underdog in this dog-eat-dog world. That is, champion and otherwise support marginalized artists, visionaries, revolutionaries, and radical networks of cooperatives, democratically self-managed enterprises, etc.

Rebel, refuse, repeat.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025