Kim Hyesoon

Kim Hyesoon

translated by Don Mee Choi

New Directions ($16.95)

by John Bradley

“On the subway train your eyes roll up once. That’s eternity. // The rolled-up eyes eternally magnified. // You must have bounced out of the train. It seems that you’re dying.”

So begins Autobiography of Death, a series of forty-nine poems dealing with death. “In Korea, we believe that when someone dies, the spirit of the dead journeys to an intermediate space that is neither death nor life for forty-nine days,” the author explains in an interview at the back of the book. With disturbing imagery and fever-pitch emotion, the poems achieve an intensity that can be compared to Federico Garcia Lorca’s Poet in New York.

The opening poem, “Commute,” introduces a disconcerting use of “you,” a technique used throughout the poem-cycle:

You shout, I don’t have any feeling whatsoever for that woman!

But you roll your eyes the way that woman did when she was alive

And continue on your way to work as before. You go without your body.Will I get to work on time? You head toward the life you won’t be living.

Note the distance between the woman who died on the subway platform and the “you,” who wants to continue on with her life, though the “you” has no body. Kim discusses this use of the second person in the interview, explaining that “As I began to speak through my death, my death became ‘you.’ My death made the I into ‘not I.’” She adds, “The ‘you’ in Autobiography is neither I, you, nor she—it’s ‘my death.’”

What prompted such an intense meditation on death? In April of 2014, a South Korean ferry sunk and 250 high school students drowned. They were wearing life vests but were told by the crew to stay inside the boat, which led to their deaths. The crew, after ordering the students to remain on board, jumped and were rescued. The translator of the book, Don Mee Choi, explains in her “Translator’s Note” that politics played a role in the disaster: “Many believe neoliberal deregulation and privatization that led to safety violations played a crucial role in the sinking of the ship, including the state’s dismal failure to rescue the passengers.” But references to this specific incident only appear in one poem in the cycle: “I Want to Go to the Island—Day Twenty.” The poem-cycle itself is non-specific, the images unattached to place or time. It’s no surprise to hear Kim say that at one point she called the book Seoul, Book of the Dead. There’s even an epigram for one poem from the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

Some readers may be wondering how forty-nine poems on death, plus a long closing poem, could be sustained. Here lies the strength and weakness of Autobiography of Death. Kim’s extraordinary talent make for a compelling book. Take this closing image from “Everyday Everyday Everyday—Day Nine”: “Your tongue is already there, flapping about like a tropical fish on the mist-/soaked asphalt.” Or this impossible to forget image from “Nest—Day Fourteen,” where Kim defines parts of the body: “Eyebrows: Two maggots trace strands of rain as they move.” While the emotions of horror and pain don’t vary, her use of poetic structure—long lines; short, enjambed lines; anaphora; and prose poems—does. However, whatever form the poems take, whatever style employed, the focus is relentless, as “Dinner Mommy—Day Twenty-Nine” demonstrates:

Today, Mommy cooks pan-fried hair

Yesterday, Mommy cooked braised thighs

Tomorrow, Mommy will cook sweat and sour fingers

Even for a poet as skilled as Kim, though, the emotions tend to flatten after forty-nine poems in the same tone. The last poem, “Face of Rhythm,” placed after the cycle ends, feels anti-climactic, as the images no longer surprise or shock: “Whale floats about inside my black pupil / Whale drags me / to the inside far away from myself.”

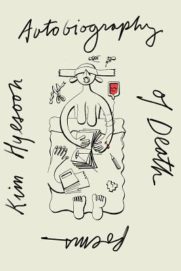

It’s likely the author was aware of the risk of an unvarying horrific tone, because the book contains ten black-ink drawings by Kim’s daughter, Fi Jae Lee. While the drawings display an appropriately dark tone, there’s also something slightly playful about them, with their wavy lines and absurd, cartoonish figures. They provide a welcome break from the obsessive focus on death.

Translator Don Mee Choi also deserves praise for her role in the book. Not only does she respond to the challenges of Kim’s demanding content and striking imagery, but her insight into Kim’s work shows in her interview with the author, as well as in her “Translator’s Notes.” She clarifies the political dimension of Autobiography of Death with her comments on the ferry incident, as well as life under President Park and “nearly two decades of US-backed dictatorship from 1961 to 1979.” She also reminds readers of the Korean War, when “About 250,000 pounds of napalm were dropped per day by the US forces.” All this helps explain the book’s deathly focus, as “All of our fingers are stained by the ink of atrocities,” she notes.

While perhaps not for all tastes, Autobiography of Death displays an abundantly talented poet who explores realms of death with great imagination, originality, and courage.