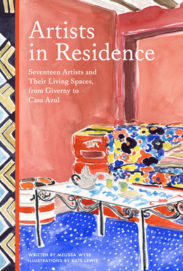

Seventeen Artists and Their Living Spaces, from Giverny to Casa Azul

Seventeen Artists and Their Living Spaces, from Giverny to Casa Azul

Melissa Wyse and Kate Lewis

Chronicle Books ($22.95)

by Linda Lappin

Recently, months of lockdown have had many of us re-adapting to our homes, repurposing spaces for new needs, dealing with clutter and chores, and straining under the limited access to sunshine, fresh air, breathing space, silence, and privacy. At some point, we all have reassessed our living space with a critical eye, wondering how to improve it—to make it more functional, comfortable, or more aesthetically pleasing, to make it a better fit for the person we are now, for the life we lead now as homesteaders hunkered down while an invisible storm rages outside.

The interior of our home is also an expression of our interior. Whether we look at Virginia Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own” or Joris-Karl Huysmans’s “A Rebours,” artists and writers have long investigated the influence domestic interiors have on their psyche and artistic production.

How do artists inhabit their homes and how do their domestic spaces shape and shelter their work? How are the homes of artists different from our own? Author Melissa Wyse and illustrator Kate Lewis address these questions in their charming new book, Artists in Residence: Seventeen Artists and their Living Spaces, from Giverny to Casa Azul, letting the reader peek into the homes of a diverse group of artists—some famous, others lesser known, representing different styles, races, nationalities and genders. This exquisite volume is illustrated not with photographs, but with Kate Lewis’s luminous paintings, in order, claims Wyse, to capture not just the “visual appeal” of an interior but also “the greater essence of how it feels” as a multisensorial reality.

The artists’ homes showcased in this book present a wide range of approaches to domestic space and to domesticity in general. Matisse relished family life and celebrated it in his work, while French-born New York sculptor, Louise Bourgeois, rejected the conventions of domestic routine. The artists discussed here also used their environments to experiment with different materials, colors, and aesthetic vocabularies, whether mirroring their dominant style or radically deviating from it. They erased barriers between domestic space and studio space, public and private, family dwelling and installation space. In some cases, their houses or apartments became organic works of art, as in the home created by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, which Wyse describes as “a three-dimensional painting that they could live inside.”

Henri Matisse, Frida Kahlo, and Hassan Hajjaj decorated their homes with explosions of color, texture, and patterns, as well as with collections of ceramics, textiles, natural objects, and art richly displayed. Louise Bourgeois loved to be surrounded by piles of books, papers, and photos: the “material traces of the past,” the “rich stores of archived memory with all its generative creative potential.” The interiors inhabited by Georgia O’ Keefe and Donald Judd express a more uncluttered, sober simplicity, yet include areas which would seem to be permanent installations, for a public of themselves.

The book has been constructed from a combination of in-person visits and archival research, since some of the buildings that lodged these homes no longer exist. The authors emphasize the need to preserve the legacies of artists’ homes which may provide as yet unexamined perspectives on their creative practice. Most often the domiciles of women and artists of color are the ones that have been lost to history, as in the poignant case of Brooklyn artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose SoHo house, which he rented from Andy Warhol, has become an upscale shop for Italian ceramic tiles. Basquiat’s memory persists only on the exterior, where street artists continue to leave their homage to his work.

For all these artists, their domestic space was one of regeneration and experimentation, a place to return to and collect oneself or escape “public interface,” making the house a safe space for dreaming. At a time when we are encouraged to remain within our own bubbles, Artists in Residence invites us to go exploring: strolling through a tangled garden in France, sipping tea at a rough plank table in New Mexico, or sitting on a plastic crate in a tiled courtyard in Marrakech. The last chapter, “Bringing It Home,” gives suggestions to readers on how to transform their own environments into “domestic installations of creativity” and open up to “the mysterious power we can access through the space around us,” inspiring us to turn our own homes into works of art.