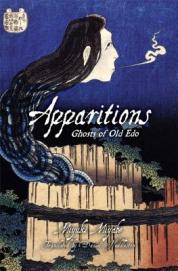

Miyuki Miyabe

Miyuki Miyabe

translated by Daniel Huddleston

Haikasoru/VIZ Media ($14.99)

by Douglas Luman

Although several of Miyuki Miyabe’s books have been translated into English, American readers may be most familiar with the 2007 translation of her fantasy novel Brave Story, her novelization of the Ico video game series narrative, or the 1999 novel All She Was Worth. A popular writer in Japan, Miyabe’s credentials in the mystery and historical fiction genres are unquestioned. It only follows that the latest translation from her oeuvre, Apparitions: Ghosts of Old Edo (originally published in Japan in 2000), is a meeting of many of Miyabe’s sensibilities. Heavily steeped in Japanese cultural tradition and folktale, the nine-story collection subtly asserts her skill as a storyteller. It exists at the crossroads of thriller and historical fiction, spanning a wide range of time during the Edo period of Japanese history, in which a rising mercantile class enjoyed success in tandem with the forces of urbanization sweeping Japan between the 17th and 19th centuries.

With this historical backdrop, Miyabe’s stories tell of the pattern that reflects the swelling wave of younger workers coming to cities to apprentice themselves to shops and craftsmen in order to begin to make a living, in most cases inheriting traditions that displace their personal histories. Of the nine protagonists, all but two are engaged in apprenticeships, the two exceptions being a kind of detective (“thief-taker”) and the wife of a successful stationery shop proprietor. All nine of the tales are closely related to some kind of mercantile outlet, providing an oblique commentary on the development and impact of contemporary economic forces. Most of the stories revolve around the beginning of each character’s tenure in their given roles, and Miyabe pursues questions of how the characters’ origins and pasts (personal “ghosts”) intersect with, affect, and inform their lives.

Advancing the form of the folktale, the collection succeeds in creating representative cultural symbols that signify more than the sum of their parts. Much like the “ghosts” that appear within, nothing is merely what it seems. Though each story takes on relatively the same form, Miyabe draws on a variety of narrative perspectives that range the gamut of storytelling voices, primarily choosing third-person or omniscient narrators whose minimal style endows the text with a strong, forward-moving pace. As the protagonist of “The Oni of the ‘Adachi’ House” claims about the workers at her husband’s stationery store, Miyabe’s characters are like “oars that row a business along, but under no circumstances take the helm . . . an oar just continues to steadily row.” There is little in the way of digression or distraction, making every word, choice, and character feel highly crafted and conscious. Often, the key to simplicity is a high degree of control over material, and Apparitions is a fine example of craft.

However, to say that the book is simply told is not to say that the narrative is without substance. Certainly, Miyabe’s prose exhibits the smooth and deliberate hand of classical storytelling but it is, overall, conscious, knowledgeable, and judicious in providing context and historical texture while avoiding moralism. The straightforward style is reminiscent of oral tradition; Miyabe’s original tales feel as if they are family heirlooms, yarns that the narrator has a clear purpose in telling. In the same way that Miyabe’s ghosts appear in certain forms or only to certain characters, the intentions or messages hidden therein are layered to support intense or casual reading tastes.

When Miyabe does flavor the text with literary style, it comes in the form of longer passages of description exploring the world around her characters, often establishing their psychological state. Landscapes are used fantastically as personas on their own. Miyabe complements her ability to establish physical geography with other passages that invoke the loneliness that plagues characters in their new lives—rivers are “leaden, gloomy, and stagnant,” for example, and other environmental features appear and recur as symbols when needed.

While characters may exhibit the typical flatness that is a folktale trademark, Miyabe’s focus on the environment around them flavors their actions and motivations, providing a surprising and subtle dimension to a time-tested formulaic style. Additionally, the use of rich historical detail, as noted in the book’s introduction, inspires nostalgia from those who have seen the regions she invokes or, among those unfamiliar with the terrain, similar enough memories that lend the stories a factual air; readers will feel as if they have been to these places before, lending accessibility to the text that crosses cultural divide. The translation by Daniel Huddleston further opens the book to Western audiences, focusing on the tangible character aspects of the narratives rather than dwelling too much on the historical facts that pepper the text. It also maintains the terse, forward momentum that the short construction of Miyabe’s sentences provides. Some may find the prose somewhat dry, but the expert pace of the stories overcomes this.

Viz Media may be more widely known for the animated and visual properties that it brings stateside, but the launch of its Haikasoru publishing line in 2009 has resulted in importing several excellent books that bring contemporary prose from Japan overseas. Apparitions: Ghosts of Old Edo is another entry in the impressive collection that the imprint has assembled, including Miyabe’s own Batchelder Award-winning Brave Story. While somewhat a departure from previous releases, Miyabe’s Apparitions is a gateway to many of the other offerings offered by the publisher under the mantra of “Space opera. Dark fantasy. Hard Science.” It should have no trouble finding a crossover audience that will enjoy this title and become interested in Miyabe’s other books.