An Interview with Kathleen Rooney

by Rachel Robbins

Some people are like clockwork, and Kathleen Rooney is one of them. She arrives at the street festival with typewriter in tow, and once set up, types quietly with her curls up in twists, composing designer poetry on topics that range from cats to corndogs. The pings of her keys, her thoughts incarnated into music, mingle with the noises of the crowd. It might stink of hot dogs and beer, but up close, I can smell her perfume. No doubt, she’ll soon unpack her homemade walnut crunch cookies in designated goody bags for her fellow poets.

I have collaborated with Rooney for a decade now, composing typewriter poetry on demand at museums, galleries, and festivals as an active member of a collective she cofounded, Poems While You Wait. Our aim is to provide city dwellers with poetry encounters in unexpected places. We write on surprising and silly topics, and the venture reminds us not to take writing so seriously. It’s also strategic; as an eternally shifting prompt with a built-in audience, it staves off loneliness and keeps us from writing into the void.

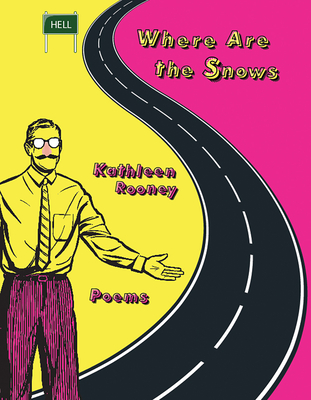

For Rooney, dedication to craft and to her writing community are serious commitments. Her newest poetry collection, Where Are The Snows (Texas Review Press, $21.95), originated in response to prompts completed as part of National Poetry Writing Month (NaPoWriMo). I have always admired Rooney’s writing for being carefully researched, conscientious of form, and for so eloquently taking on hard topics. As an individual, she is brazen about the value of women who disagree (on Twitter, she often declares an “unpopular opinion alert”). This book, as exemplified by its “Highway to Hell” cover art, is a trip through the valid, uncomfortable, hilarious, and essential side streets of our private thoughts. If Kathleen Rooney were a scent, Where Are the Snows would be her essence bottled in a perfume.

In addition to her other achievements, Rooney is a founding editor of Rose Metal Press (a nonprofit publisher of literary work in hybrid genres), the author of several novels (most recently Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk and Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey), a prolific reviewer, and a teacher at DePaul University in Chicago.

Rachel Robbins: Let’s begin with the beginning. Your new book opens with costumes; what interests you about disguise, or rather, the failure of disguise? Why do you think we continue the charade if the intended meaning and received meaning don’t align?

Kathleen Rooney: Whatever else it is—and it can be a lot of things—I like for poetry to be entertaining. Above all else, I want this book to be fun. I want people to get their money’s worth. The opening is me dressing up and taking the stage, like Welcome to the show! Even if you don’t like or understand everything you’re about to see, I hope you’re glad you came.

RR: The collection is definitely humorous and playful, even as it takes on severe issues from politics to climate change. Elsewhere, it feels hopeless—you even write about giving up hope for Lent. Where does writing figure into hopelessness for you? Specifically, why poems as opposed to essays?

KR: Some problems are so bad they cannot be fixed. If you say that, some people will think that you’re hopeless. But sometimes, admitting the scope of the problem can be a way to stop sitting in denial and create new paths to hope. For example, me sorting and quote-unquote recycling all my single-use plastic and dutifully placing it in the proper Dumpster? That’s not going to save the Earth. But saying so is not hopeless, nor is it necessarily giving up. It’s ideally opening the door to reading a book like Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline and then blowing up a pipeline. New hope!

I didn’t want to write nonfiction or a manifesto, but just to spend time in a mindset where, because these are poems, I could let myself think in new ways without worrying about having all the answers; rather, I could make space for greater honesty and new answers.

RR: A line that stays with me is, “You won’t believe how saintly I’ve become. Big halo energy.” This is one of those moments that makes us laugh, but it’s also uncomfortable because it calls out the showmanship involved in performative morality—Ukraine filters on Facebook or the infamous black square on Instagram. Can writing be politically correct while continuing to make meaningful change? Is the publishing world afraid of hot-button topics?

KR: In spite of the hypocritical and pernicious influences of such religious extremists as evangelical Christians or far-right-wing Catholics like Amy Coney Barrett, America is a largely secular society. But humankind needs to believe in something bigger than itself and to connect to other people through that thing—a mystical thing, a metaphysical thing. To be clear, the abandonment of the historically oppressive structures of religion as a means to abuse and control is for the best. Misguidedly, though, a lot of people seem to have sublimated this impulse to organize ourselves in a church-like fashion into an obsession with purity and correctness, resulting in some quarters—quarters that include academia, the arts, and publishing—having a Spanish Inquisition-style bloodlust for hunting down the impure and making them suffer and pay. I find this gross. I want a life with a real spiritual dimension (whether it comes from art, from service, from community, wherever), but I want that dimension to aim at ecstasy, not agony. Why are so many people choosing agony? Even if you think you’re only inflicting agony on people whose politics do not meet your immaculate standards, the reality is that you are not really changing hearts and minds (all you are doing is adding to the already inexhaustible supply of resentment and grievance that characterizes much of the so-called discourse), and you are corrupting your own soul or whatever you want to call it as well. Why not try to unite around solidarity, joy, and fun?

RR: There is so much humor in the taboos. You pinpoint the way we constantly lie by asking: “What might happen if I signed my emails ‘derangedly’ sometimes?” You don’t mince words. You write, “Sometimes a friend posts a photo of their newborn and it’s all I can do to not type, / Welcome to Hell!” Do you ever hesitate to publish work that voices uncomfortable or unpopular opinions? Why do you think it is important to say them? And why do you choose to say them in a joke?

KR: Lately I’ve been asking myself the question: does the Left hate fun, and if so, why? The best charismatic leaders—Malcolm X, Florynce Kennedy, Gloria Steinem—know how to be funny. They quip. They tell jokes. So do the worst, including the odious 45.

The Left—as well as anybody who wants life to be beautiful and just for the majority of living beings on this planet—needs some more funny charismatic leaders, and that is hard to achieve in the current circular firing squad arrangement, where paranoia is ubiquitous, everything is suspect, and the instinct is to distrust even—or especially—the people who are on your own side. Through humor, you can point out unpleasant and disquieting things, and if you can point them out, then maybe you can address them.

RR: Time and again, the poems shift from gut-punch humor to existential loneliness, and in that pivot, the reader is caught unprepared. This makes the impact of the profound and painful more pronounced. By making us laugh, you catch us off guard. One that particularly stuns me reads, “Once in a while, the pigeons undulate across the blue void in such a way that I wish I/ could join them.” How do you hope we will feel after reading your poetry?

KR: I hope you will feel like that. Unburdened and free, like beauty exists and anything is possible.

RR: There is a beautiful confusion between our “civilized” human world and the forces of nature in statements like, “Lake Michigan churns like a washing machine,” and “the distant thunder of the toilet flushing.” Do you aim to remind people that they are animals? Why?

KR: I do! Human supremacy is a mistake and a death-trap. We are creatures. There’s no separate capital-N Nature. There’s no outside, there’s no away. (When you throw your trash “away” it sticks around somewhere.) Thinking we’re separate and superior has gotten us into the worst imaginable catastrophe, and we’ll need to stop thinking that if we hope to get out.

RR: This collection spends a lot of time exploring etymology and word relationships, questioning how/why things are named. It lingers over bluejays that have nothing to do with jaywalking and features dust bunnies who hop. After all its permutations and evolution, does language start to lose meaning? Why do we say things without meaning them?

KR: We say things without meaning them sometimes because we want to believe them even if we don’t, because they’re easier or more comforting than the truth. Or we say them because we want to signify a certain attitude that will help us fit in and belong. I hope the book makes people think of that, but also that it helps them just think about the magic of words. The depths and layers and histories each individual word arrives to us carrying. Every word is a time capsule, an artifact, a magic spell. Words are such a great medium because unlike paint or musical notes or clay or whatever, everybody uses them, so the challenge as a poet is how to make a poem out of something so common and familiar. I love that challenge.

RR: It’s a bit like if a tree falls in the woods, but you ask, “Can you have a moral / code without other people around?” Can you speak to the role of audience in your work? What impact does audience have on your sense of self?

KR: During the pandemic, I—like many people—disintegrated. I lost almost all relational sense of self. I have rarely been so lonely and excruciatingly miserable in my entire life.

I am weary of discourse that reduces people into fixed entities saying what they are rather than what they do. So when suddenly, there was almost nothing to do and no way to see other people, I had a rough time. I respect when people say, “I just write for myself,” but I write for myself and other people; it’s always both simultaneously. I love the literary community and the support and solidarity that can come from a group of people who love a shared activity. So I always write in the hope of finding an audience. I want to connect and communicate and laugh and cry with other people. Those things make me who I am, and make everybody who we are.

RR: Let’s talk about motherhood and shame. In “A Human Female Who Has Given Birth to a Baby,” you admit: “This is a poem that will make a lot of people hate me.” That you felt it necessary to include the preamble speaks to the rampant sexism women face whether they bear children or not. What do you want women to know about motherhood? Is the expectation something you brace against?

KR: One of my male colleagues at DePaul told me at a cocktail reception that I would “never know real love” because I have opted not to become a mother. That notion is bananas to me. And it’s bananas in a way that illustrates one of my points about motherhood, which is that it’s a raw deal, and if were not such a raw deal, then people would not constantly be trying to sell it as a great one. Being a mom can be rewarding, but dude, it’s also incredibly hard. This country despises women in general and mothers in particular (see what’s happening with Roe and also the fact that our government and employers give virtually no parental leave or other material support whatsoever to new parents). Any time people go around saying these kinds of platitudes—that the family is sacred, that motherhood is the means to actualization and purpose, that the only true love is mother to child—and saying them so aggressively and repetitiously, that should be a clue that these platitudes simply cannot be true. They are lies. Expedient lies designed to coerce women into following the social imperative to sacrifice themselves. Anything self-evidently true does not need to be so rudely and desperately repeated. I wish I’d said to my colleague in that moment that the nuclear family is a death cult. Wit of the staircase, I suppose, but maybe he will read this and see it now.

RR: Throughout the book, there’s a lingering certainty of the impending collapse of society. Is America really “a hellbound train even Superman can’t stop?” Is this a collection about the apocalypse, or is it something else?

KR: The apocalypse is a luxury that only people who think it will somehow spare them can believe in. The apocalypse suggests something cataclysmic and finite—something with an end. In reality, all of our collective suffering—from economic inequality to a lack of free public healthcare, climate change, you name it—will be much more of an endless slough of despond, just a totalizing slog through unimaginable but interminable misery. No one will be spared.

That being said, my point about Superman is less that this is a hopeless apocalypse and more that we’d better put on our own capes (ideally, per your great question about disguises above, really cool-looking capes) and start saving ourselves and each other.

RR: It fascinates me that many of these poems are derived from facts. What exactly is your passion for research? Does it feel different researching for poetry than for prose?

KR: As the alliterative expression “fun facts” expresses, facts are fun. In both fiction and poetry, I enjoy finding the most fun (as in surprising, beautifully phrased, emotionally evocative and so on) facts that I can and seeing where they take the piece. In both genres, too, facts help me explore how even phenomena that are demonstrably true can be—and maybe even have to be—processed subjectively. I read an interview with Werner Herzog (whose use of research in his films I admire a lot) in which he said, “I do believe that to a certain degree we all live a certain fiction that we have accepted and articulated and formulated for ourselves. We are permanently in some kind of performance.” Research helps me construct the performance that is my poetry and novels. And probably the performance that is my existence itself.

RR: You write, “In a way, we all live on Lonesome Lake now.” Do we? What do you mean by this?

KR: I don’t know if we all do, but I know that the forces of rootless global capitalism and coercive technology are pushing us to live there—conditioning us to perceive other people as competitors and threats, incentivizing us to conduct our lives through screens. But we can say no. We can see other people as allies and friends, and we can conduct our lives face to face in real places. To a large extent, we got ourselves into this mess, but we can absolutely get ourselves out.

Click here to purchase Where Are the Snows at your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022