by William Corwin

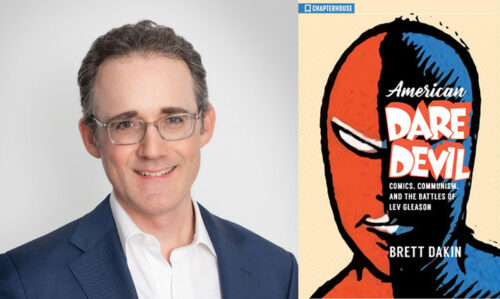

Brett Dakin‘s recently published Eisner Award-nominated biography, American Daredevil: Comics, Communism, and the Battles of Lev Gleason (Comic House, $24.99), tells the story of a real-life character who not only published over-the-top crime and superhero comic books during the industry’s “Golden Age,” but also spent weeks in front of the House Committee on Un-American Activities defending free speech. Dakin also delved into the more recent past in his 2003 book Another Quiet American: Stories of Life in Laos (Asia Books), and in our conversation below he unpacks the difficult task of presenting authentic narratives, transcripts, and dry research in a literary form. Some authors have found the solution is to write a fictional narrative to create some distance between subject and author, but Dakin—perhaps because of his legal background—has chosen non-fiction, which above all requires that the writer sit back and listen.

William Corwin: American Daredevil is a biography of Lev Gleason, your great uncle and a man who was active in many things, most notably as an early publisher of comic books. Your first book, Another Quiet American, was a memoir of your two years in Laos. Talk about the difference in your writing process between these two.

Brett Dakin: In the first book, the narrative was determined by things that happened, meaning the book is generally a retelling of the events in the order in which they occurred. In the second book, there were things that happened in the past, but the timing of my learning about those things was not necessarily consistent with the timeline of historical events. So I was faced with this choice. Should I write just a straight biography, i.e., “Uncle Lev was born on this date, and died on this date, and these things happened in between,” and remove myself from the narrative altogether? Or should I tell the story as I discovered it? What I ultimately ended up doing was a bit of both, which is to tell his story in a roughly chronological order, but also to give the reader a little insight into how I discovered pieces of information, because it wasn’t always that clean or neat a process.

WC: When was the moment you decided this person’s life would make a good book?

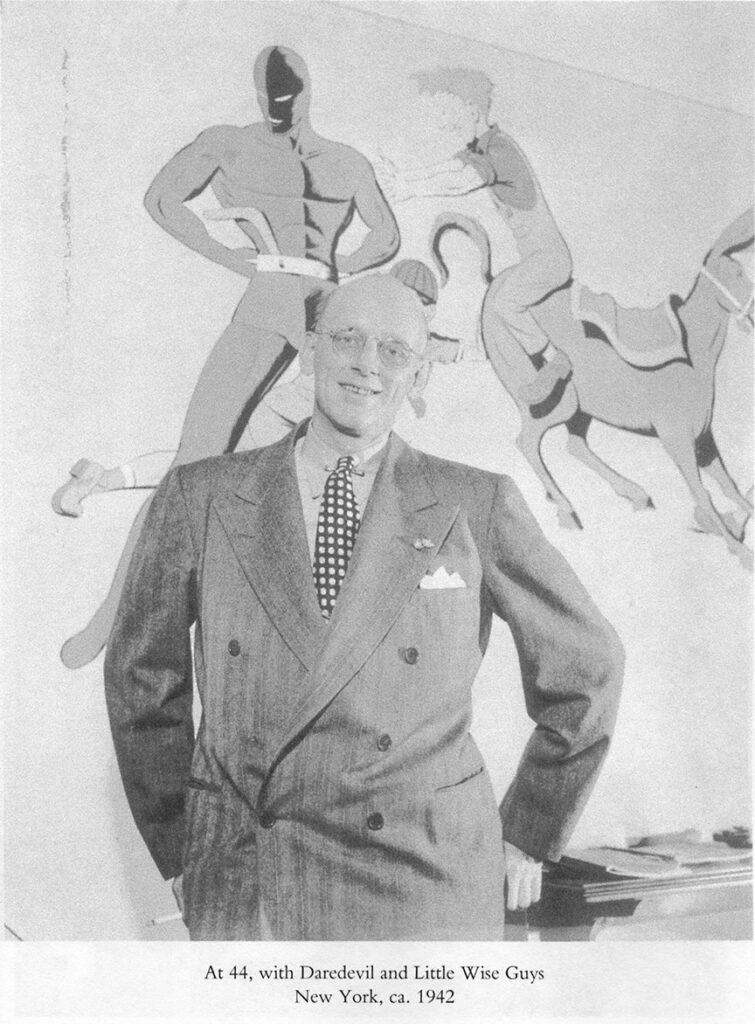

BD: I grew up hearing about Uncle Lev, but it never occurred to me to write about him, or even try to learn more about him. I heard stories from my mom, who was his niece, and he always struck me as a colorful character—I was taken with him, but from a child’s perspective, the same way that growing up I was taken with Drosselmeyer in the Nutcracker. I always thought, “Wouldn’t it be cool to have someone who swooped into town and showered all the children with gifts,” which is exactly what Uncle Lev would do with my mom and her friends when she was a child.

WC: More interestingly, there are also stories about Uncle Lev leaving the country and hiding, or ending up in prison . . .

BD: Yeah, well, those are not stories that my mom told me. The amazing thing that I ultimately learned was that in the community of comic book scholars, there was a lot of conjecture about where he went after things went south for his publishing business. But to get back to your question, I first started thinking about writing about Uncle Lev because I read Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (Random House, 2000). Kavalier and Clay is a fictionalized account, with completely made-up characters, but set in the very milieu that Uncle Lev not only lived and worked in, but helped create, because he was there at the birth of comic books in the 1930’s in Manhattan.

WC: And you communicated with Michael Chabon! Did he know about Uncle Lev? Had he heard of him?

BD: Absolutely, yeah. When I reached out to him, he was extremely excited to learn that someone was writing a book about Uncle Lev because he knew what a fascinating figure he was.

WC: How had Chabon found out about him?

BD: By reading—certainly my book is the first historical account dedicated to Uncle Lev, but he had appeared in histories of comic books in the past. So Chabon knew enough to realize that he was a fascinating figure. It was one of those moments when you see how fiction can spark an interest in history and that’s what it did for me, so I decided, let me figure out what Uncle Lev’s role in all of this was. The first thing I did was to go to the archives at Harvard University, because Harvard was where Uncle Lev went when he graduated from high school.

WC: Uncle Lev was sort of a litigious figure, and a litigated figure; one of the things that comes through in your book is that you elucidate many of these passages from documents from when, say, Uncle Lev was brought before the Committee on Un-American activities. Perhaps it’s a credit to your lawyer background, but you make this kind of writing and discussion interesting, these judicial verdicts and things like that. Was that something that drew you to the project—you said you had just graduated from law school, and you must have had an inkling that Uncle Lev had a lot of legal interactions.

BD: Again, to be honest, when I graduated from law school, I did not know that Uncle Lev had been so litigious and had been the subject of so many judicial and other inquiries, but I soon found out. But yes, that aspect of his life made me more excited because I’m a lawyer, and so reading court opinions, transcripts of hearings, of trials, of committee meetings, is something I enjoy—which I suppose can’t be said for everyone. What I tried to do in the book was take those proceedings, which can be rather dry in transcript form, and bring them to life on the page. I situate them in the context of what was going on in Lev’s life and in the comic book industry and the antifascist movement at the time. For me it was a natural fit—maybe given the fact that I went to law school and did the bulk of the research in the period right after I graduated and before I went to actually work at a law firm.

WC: In dealing with the accusations that were leveled against Lev, what mindset did it put you in to read those transcripts of conversations between, say, the FBI and your uncle? Did he seem frightened? Did they seem intimidating? Did you feel it was all political and smoke and mirrors? Very few of us have ever actually looked at FBI transcripts.

BD: One of the first things I did was I consulted the good-old-fashioned New York Times index, since at the time I was still in the frame of researching things by going to books with indices in them. I remember looking him up and being flabbergasted to find he was there. That solidified my thinking that there might be a book here, but one of the categories under which he was placed was “treason.” I was totally shocked by that. The reason was that he was accused of being a communist and categorized with people who were considered to be advocating the overthrow of the United States government. My feeling now is the same as it was then, which is that it was totally absurd—nothing could have been further from the truth in the sense of Uncle Lev’s view of the United States government, which was extremely positive. He was a strong believer in FDR and in the American democratic experiment; he served in World War One and in World War Two; he deeply loved his country, but also was deeply critical of it when he felt necessary, which is exactly the way I would categorize myself. So I was kind of shocked and a little bit disturbed to find that “treason” was the word that was associated with Uncle Lev at the beginning of my research.

The next part of the process was looking into it and seeing what their evidence was of that. And the fact is that the FBI—and I obtained his file—tracked him for more than a decade. I read through the entire file, along with reports of Uncle Lev in the U.S. army, in House Committees, in New York State Legislative committees. I mean he was investigated by all sorts of bodies for various reasons, and there was never any evidence to suggest that he supported the overthrow of the United States government. He lived a perfectly comfortable and happy life in the suburbs of New York for most of this period, commuting to Manhattan every day in a chauffeur-driven Packard; the idea that he would want the system that had been kind to him to collapse struck me as absurd from the outset. Now, on the other hand, it’s very clear that Uncle Lev was moved by the principles of the communist party in the United States, but his ultimate goal was to stamp out fascism, in Europe and in the United States. To him those threats were very real, and today we are seeing that those threats remain very real. He fought against it in his political activities and in his comic books.

WC: Let’s talk a little more about your method of writing: Do you take copious notes? In your previous book, Another Quiet American, there are stories of you teaching English to a General in Laos, going to rallies, and interacting with various characters—bureaucrats, expats, sometimes romantic involvements. As a writer in a foreign country, did you sit down at your desk every day, were you keeping a journal? And did you go into this experience thinking there was a potential for a narrative?

BD: I did. I went into the experience open to the possibility of writing about it in some form. I lived in Laos for two years; the first year there was less writing and more living. I didn’t keep a diary, but I definitely jotted down notes and thoughts as I went along. But the second year I began to write about my experience, so I would dedicate a portion of every day, usually at night when I was at home after being out and about in Vientiane, the capital. I would not just take notes but write in narrative form, stories of the people I’d met and the experiences I’d had. Those vignettes formed the basis for the manuscript that I put together after I had left the country and I spent a lot of time writing it when I was living in Vienna—from a remove I could see better how those stories could come together into a coherent narrative. By the time I moved back to the U.S., I had something I could shop around to publishers.

WC: When it was time to go through your notes, what was the process? Was there a sizeable amount of change in terms of writing or was it mostly just tidying things up and framing them, choosing which stories to tell?

BD: Well, first, there was a lot of cutting because I wrote about some things that upon further reflection were not that interesting, or that I didn’t think would be interesting to an audience other than me. A lot of prioritization went on, sifting through and drawing out the stories that might be most interesting to a general audience. Then another part of the process was taking stories and contextualizing them—situating them within the historical or societal context. If I were writing the story of a particular expat that I met, for example, I would really spend some time researching the relationship between the country that person was from and Laos. So that was a matter of fleshing out these stories so they weren’t just me saying what I did or heard but also backing it up with other sources or just situating the stories in a larger context, so the book would have value to someone who wanted to learn about Lao history and culture and society. Ultimately, I never viewed the book as a book about me. Obviously, I am the narrator and the main character, I suppose, because I’m always there, but I always viewed myself as a vehicle through which to tell other people’s stories.

WC: There’s a wide spectrum of literature involving an outsider coming to a country in the midst of upheaval. It can be enlightening, but also colonialist, so it’s a problematic body of literature, regardless of whether it’s self-critical or not. How did you address that in your book?

BD: Well, I try not to skirt the issue but write about it, to write about my struggles with my role as an American in a place that had been heavily bombed for years by the U.S. military—and bombed with, if not the explicit, then the tacit support of the American people. We were not fully informed about the so-called secret war in Laos, but had we been, would there have been an uproar such that the bombing of Laos and Cambodia would have come to an end sooner than it did? I’m not so sure. Frankly, it seems doubtful given what we know about public opinion regarding the war, which was always relatively strong until the very end of that long and horrific period in American history. So I try to write about my mixed feelings about being in the country and really try to listen more than talk, to suppress opinions that I might have and solicit other points of view instead, and I think that helped me to write better stories, because frankly I wasn’t a main driver of the things that happened to me while I was living there. I was allowing other people to drive the narrative; as the title hints at, Another Quiet American: Stories of Life in Laos isn’t really about me, it’s about the people that I met and their stories.

Click here to purchase this book at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2022 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2022