photo by Michael Amico

by Benjamin Davis

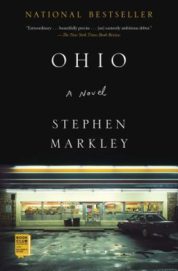

Stephen Markley was writing about opioid addiction and rust-belt voters before the issues hounded the headlines. Those stories came together in his debut novel, Ohio (Simon & Schuster, $16.99), a book that began as a murder mystery and became a large-scale social commentary. Called “a kind of fiction/op-ed hybrid” by The New York Times, Ohio, in its prescience and politics, is a book for the present. I reached out to Markley after attending his reading at Houston’s impressive Brazos Bookstore; in the following interview, we discuss writing about the Midwest, gender in literature, and the question of home.

Benjamin Davis: In his Paris Review interview, Jim Harrison claimed that there’s no such thing as regional literature; either it’s literature on aesthetic grounds or it’s not literature at all. Ohio flags a region from the very title. Can you say more about how the novel nevertheless speaks broadly in this moment?

Stephen Markley: Ok, I don’t want to kick off this interview sounding like a dumbass, but can I admit I don’t know what Jim Harrison is talking about? I literally just do not understand. All I know is that I never go in for lit that feels airless and floating, that tries to be “timeless” but in doing so just comes off as plastic, sterile, and antiquated quickly anyway. Something I adore and admire is when an author makes you feel like you know and understand a place you have never been. Or even better, you have been there, and you can’t believe how much they’re nailing it.

BD: Bill is an activist who has been through a lot. Where did the inspiration for him come from?

SM: I’d say there are two components involved. First, after college I thought I’d dive into politics and/or activism of some kind, and it’s not like I’ve never been involved in those realms since, but I quickly discovered I do not have the temperament for it. It can create this womb around a person, this detachment from the perspectives and experiences of anyone outside the womb, an intellectual cloistering. It’s also extremely frustrating work. You fight like hell your whole life for dignity and justice and all that, and at the end of it your neo-fascist reality show star president walks you off a plank into a pool of sharks to great ratings. This is not to denigrate the people who do that kind of incredible and grueling work, but instead of an engaged and energetic citizenry, we have a model where activism becomes a full-time identity until it breaks your heart and you burn out. You either drink yourself to death or go work on Wall Street and tell yourself Ayn Rand had it right. That’s where I found Bill, attempting the former.

SM: I’d say there are two components involved. First, after college I thought I’d dive into politics and/or activism of some kind, and it’s not like I’ve never been involved in those realms since, but I quickly discovered I do not have the temperament for it. It can create this womb around a person, this detachment from the perspectives and experiences of anyone outside the womb, an intellectual cloistering. It’s also extremely frustrating work. You fight like hell your whole life for dignity and justice and all that, and at the end of it your neo-fascist reality show star president walks you off a plank into a pool of sharks to great ratings. This is not to denigrate the people who do that kind of incredible and grueling work, but instead of an engaged and energetic citizenry, we have a model where activism becomes a full-time identity until it breaks your heart and you burn out. You either drink yourself to death or go work on Wall Street and tell yourself Ayn Rand had it right. That’s where I found Bill, attempting the former.

He’s also proven the most controversial character. Some people hate him, can’t even get through his chapter, and some love and/or identify with him. This bookseller in Pennsylvania told me, “I couldn’t understand why everyone hated him. I adored Bill! I dated him in college.” Which made me laugh because it’s not the first time I’ve heard that. Then I was talking to my friend Nancy, who was a total lunatic in college and also one of the smartest people in the entire student body, and she said, “Oh, I thought Bill was based on me.” And she’s kind of right in that I’ve always had a fascination with people who give zero fucks what people think of them, who do not care about anyone’s pieties and who have the intellect and precision to back up their bluster. They’re volatile and mesmerizing and nasty in a lot of ways, like the plutonium of human beings. If Nancy somehow gets famous she’ll be canceled after her first thirty-five seconds on Twitter. (I’m mostly just kidding, Nancy’s great.)

BD: What guided your decision to tell this story through point-of-view characters, weaving different experiences together around a single night in a single town?

SM: It’s hard to remember the exact evolution of those decisions. What I can remember is that I always, always, always had those four voices in my head. So much so that by the time I sat down to write the actual words that would make up the book, I’d been living with these characters for quite some time.

BD: Did you at any point feel a pull to write about Chicago, Los Angeles, or other cities you know?

SM: Nah, not really. I mean, I wrote a bit about Chicago in my first book, but I don’t really approach storytelling like Oh, now it’s time to write about L.A. (“Traffic sucks, it’s too sunny, this Bumble date thinks I have way more money than I do, The End”—terrible novel).

BD: It’s worth noting that the book is rural in its focus. I look for Ohio when I travel now, and I see it selling at little bookstores in hip neighborhoods and in wealthy liberal enclaves in cities, yet it is a book about a small town. Thankfully, you avoided writing as one of those “here’s how to understand Trump country” books that are now popular. Still, did you have a readership in mind when writing it?

SM: I take that as a great compliment because the last thing I ever want to do is claim to speak for anyone about anything. I wrote the entire novel and was well into, I think, the fourth draft before Trump was even a gleam in the eye of a thirsty media conglomerate. So I didn’t set out to write about the zeitgeist; I wished upon a monkey’s paw, and the zeitgeist crashed into my book (“Please let me have a successful debut novel, and I don’t care what socio-political circumstances arise to make it thus!”). As for the readership, I’m just glad someone read it besides my mom.

BD: You write about deindustrialization in New Canaan, then note “but nowhere in the Midwest really escaped.” Can you paint in broad terms what aspects of deindustrialization you wanted to cover, what specific elements stay with you that we see across the Midwest?

SM: Keep in mind, by the time I was old enough to be aware of much of anything, the Midwest had already gone through the worst spasms of deindustrialization. I wasn’t born yet when the steel plants in Youngstown started closing, so I grew up in the Walmart-ized version of a once-great industrial region. But I always found an odd beauty to a closed factory sitting abandoned in some weedy, chain-linked lot because it’s impossible not to let it capture your imagination. This place used to make something, and people were friends here, and there were stories here, people met their husbands and wives here, and now it’s gone, and all those stories are confounded ghosts, wandering, and likely no one will write them down or remember them. There’s something heavy about that.

But politically speaking, the most deleterious effect of deindustrialization was capital’s war on organized labor. The main reason capital began the project of offshoring was to break the backs of the unions, and it worked exceedingly well. Now what do you have? A lot of big box stores and Amazon warehouses where the managers are mostly trained in union busting. So not only are you losing the union’s power to negotiate for wages and working conditions, you’re removing the primary political organizer for a community of working people. I don’t think it can be overstated how toxic this is. Putnam’s Bowling Alone touched on this: that de-unionization tracks precisely with economic inequality and, beyond that, the decline of social capital (people’s networks and connections within a community). As wages stagnate and social capital vanishes, what moves in? Opiates, meth, pills, alcoholism, sure, but also political philosophies constructed of grievance that seek to place blame, usually on some convenient Other.

BD: You have said that you started out writing a murder mystery, but realized you had a lot more to say. And indeed, the book takes on a lot more, including political questions. How did you realize you needed to say this “a lot more”?

SM: I’d been writing opinion pieces for a while, so I’d always had a political bent, but my fiction was sort of a separate category—I didn’t necessarily see it as political. This allowed something important to happen, which is that the politics arose organically from the viewpoints of the characters, none of whom precisely shared my particular worldview. And that’s the beauty of writing fiction: when you’re really doing it, you are Really Doing It. You are this other person, and you inhabit their mind and their thinking, and it just makes a certain sense to you because that’s the way this make-believe person sees it, and there’s nothing weird about that. So I set out to write this complex mystery in which you had no idea what the mystery even was until the last twenty or so pages, but then reading the first draft, I got a sense of the rage and sorrow each of these people felt, and how that rage and sorrow was connected to the events of their adult lives, including war, addiction, homophobia, recession, and the other themes the book touches upon.

BD: As a Minnesotan, I can testify to your getting a lot of Midwestern language right, such as the way people start sentences: “Thing was, Bill had a hard time . . .” How important is colloquial language to you?

SM: I love the way people talk—it’s such a specific fingerprint, right? But you can’t really fake it, so I guess I didn’t even notice that I’d started sentences that way. Here’s an even bigger bombshell: I don’t think most writers even know what the fuck they did until they’re on the book tour and people are asking them questions. Then we’re like, “It was very important for me to utilize colloquial language . . .”

BD: You have a way of reminding us that our actions go home, that what we do is not only informed by where we’re from but also returns there. “What an important lesson for every young person to learn: If you defy the collective psychosis of nationalism, of imperial war, you will pay for it. And the people in your community, your home, who you thought knew and loved you, will be the ones to collect the debt.” Can you say more about this phrase—“the collective psychosis of nationalism”?

SM: I can’t recall who I stole that phrase from, but I don’t think at this point it’s remotely controversial that nationalism is toxic and that its permutations can defy all attempts at reason. My perspective is that I came from a generation that reached adulthood almost exactly on the day of 9/11 (literally, two of my best friends turned eighteen on 9/12, and I turned eighteen less than a month later). So to slip into Bill’s perspective, here’s what he might say: “And what came of 9/11? A burst of hyper-nationalism not seen in a generation, followed by two catastrophic wars, which are probably going to cost between five and six trillion dollars when it’s all tallied. There are now stories of fathers and sons having gone on the same patrols in Afghanistan. Iraq remains a broken country littered with the bodies of innocent people. And this is to say nothing of disastrous interventions in Libya, Syria, Pakistan, all across North Africa, and you better believe if Donald Trump wants his war in Iran or Venezuela, some not insignificant faction of the American polity will go along with it, and a whole new tragedy will commence. This is to say nothing of the concentration camps rising along the U.S.-Mexico border, which will likely expand in scope well before any future administration manages to shut them down. To call all of this ‘madness’ is an insult to madness. But we go along with it, and some of us love it. Because nationalism is like religion in its power and ability to rally people to just about any half-baked notion you can dream up.”

Again, when I wrote Bill Ashcraft, I didn’t really expect him to be this correct about everything.

BD: There’s a lot of masculinity going on in Ohio. For instance: “Adolescent identity is an odd thing, formed mostly for hypermasculine young men by their chosen extracurricular activity.” And: “his dad shook hands with Mr. Clifton, because he literally could not converse with another man without a firm handshake first (even if it was a neighbor and friend of nearly thirty years).” Why was this important for you to comment on?

SM: You have to keep in mind that those two instances are from the POVs of the two male characters (the female characters, of course, have their own less-than-pleasant experiences with masculinity). Again, because the book was written so long before the MeToo moment, it’s like the zeitgeist crashed into the themes I was working on. Something I keep in mind is what my mom once said to me, “The patriarchy isn’t just bad for women; it’s bad for you too, bucko.” In that it confines men to these dangerous boxes, fuels them with horrific notions and demands, drives them so easily to despair when they have no shot at living up to those demands. Bill probably knows all this, but he’s somewhat helpless to fight against it. Dan intuits some of the absurdities of masculinity, especially because he grew up as someone who was having his masculinity challenged—a bookworm who decided to join the military.

BD: What were your working habits on the book? Did you return to the state frequently, making the book a kind of ethnography? Or was it written by memory from Iowa?

SM: I mostly wrote it while attending the Iowa workshop, but I didn’t really need to research Ohio per se because I was going back home fairly often, as I have been in the years since I moved away. Most of the research revolved around Dan’s experience in the army and Stacey’s doctoral thesis, of which I ended up cutting about 98%.

BD: At one point you take on a story of an Ohio Union colonel who switches, through his experience fighting in the Civil War, from an anti-emancipation Democrat to someone opposed to slavery. “It must be a shaming, damning, beautiful moment to understand such a thing. To have your heart changed.” Do you think a novel can contribute to this? Or, how do you think about the role of the social novel—the “Big American Novel,” as it’s been called.

SM: As smarter people than me have pointed out, the “Big/ Great American Novel” moniker adheres a bit too frequently to white bro authors, so I sorta throw my garlic and crucifixes at that phrase and run away screaming. However, of course I think novels contribute to an inner life and a higher consciousness and an ability to feel empathy and reason and passion in a way almost no other art form can possibly accomplish. I have to believe this or I wouldn’t do it. And from my perspective, I live in the most consequential economic and military empire in the history of human civilization, which is also undergoing a series tectonic shifts—some good and most not so good at all—so that’s pretty interesting.

BD: There’s a lot of talk these days about who can write what and who can read what. I doubt the response to a white man’s attempt to write an indigenous female protagonist would be similar to Louise Erdrich’s blurb on Jim Harrison’s Dalva: “Monumental . . . Bighearted, an unabashedly romantic love story . . . There is no putting aside Dalva.” Can you talk about your approach to writing Stacey and Tina?

SM: I get that question an awful lot, so here’s a chance for me to give my long answer, which will use the equivocating phrase “having said that” twice, and hopefully inspire a media firestorm that will sell more books:

We are in a moment when people from marginalized communities and identities are stepping forward and saying, “Hey, what the fuck? It’s my turn, you fucking bearded white guy.” This, I believe, is unabashedly one of the Good developments I referred to earlier. In terms of the light speed with which society and capitalism has reorganized itself to recognize and celebrate LGBTQ rights, it’s sort of astonishing. If you had told me in high school that someday Verizon would be sponsoring Pride floats, I’d ask what alternate reality you’d flown in from. This is also leading to a proliferation of art and ideas and public figures from corners of the human experience that simply weren’t reaching mainstream audiences before. It’s really fucking awesome, and when I’m staring at the ceiling in the dark of night worrying that our slide into fascism is unstoppable, I remind myself that the most important American politician right now is a Puerto Rican bartender from the Bronx promoting the most confrontational vision of social democracy I’ve heard in my lifetime.

Having said that, I believe it is the prerogative of the artist, the writer, the filmmaker to believe totally and fully that nothing is ever, ever, ever off limits. To write with invisible social critics on your shoulder is total doom, and part of the journey and the POINT of creating literature is to imagine yourself into someone else’s shoes, to envision what this stranger’s fears and heartaches and hopes are about, and in the process to let that change your heart, even if just by a little bit. And I seriously don’t care if I’m the last person on that flooding island, clinging to the rocks by my fingernails. I doubt I’ll ever write a novel told solely from the perspective of a straight white man because that is seriously boring, and not even in accord with my own experience of living in the world and the people that matter to me and the building of my own consciousness from the influences of all the non-white, non-male artists, leaders, and visionaries that I have so desperately adored. If tomorrow it becomes unacceptable to write from anything other than your own “lived experience,” and the whole of the publishing world refuses me, I’ll gladly just keep writing and leave the pages in my drawers to be unearthed after the seas rise and civilization collapses and is then again reborn and everyone finally looks around and says, “Oh yeah, I guess we were in this thing together the whole time, weren’t we?”

Having said that, I’m definitely not arrogant enough to believe I can truly ever know what it’s like to go through life as a queer woman in a place hostile to your identity in every way. I’m under no illusion that this is an experience I can in any way own or claim to speak for (like I said, never speak for anyone but your own dumb self). My formula therefore is to write with bravery, but edit with humility. I told the story I had to tell because it was screaming inside of my bones to get out, but when I turned to the editing process I of course sought advice from some of the smartest women in my life, who also had the energy to read and comment on a 500-page novel. Going through the journey of writing Stacey and Tina was something I never treated lightly, and I kept in mind my responsibility to people who’d had those experiences.

BD: “Home is a roving sensation, not a place, and for a large chunk of his life, the feel of that bullet to the chest, that was home.” Is Ohio a kind of homecoming for you? What did writing it teach you about home, place, belonging?

SM: Home is a kind of spirituality. It inhabits you and influences you no matter where you are, who you think you are, or who you think you can become. Watching one’s home suffer degradation, depredation, or tragedy, you realize how fragile it is, how foreclosures, recession, opiates, or any number of exogenous influences can rock it to the core. Thinking about one’s home in this particular historical moment, it all must be framed within the context of displaced peoples, refugees, asylum seekers, and the greatest mass movement of human beings since World War II. Much of that movement is the result of those aforementioned catastrophic wars in the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia but also the early onset effects of our ecological crisis. The UN tells us over 65 million people have been displaced, and given that nothing is being done to arrest climate change, that number could be as high as 250 million by the middle of the century, according to some estimates. In that context, the idea of home is going to take on vastly different dimensions in the human imagination, even for those of us in the comfortable West, because in the midst of unpredictable climatic and political convulsions no one’s home is going to be safe. Not really. So I think the idea of home should remind us not that we’re a part of this cloistered region or that protected enclave but that, again, our individual fate is bound up in the fate of the entire human community, in ways both obvious and subterranean.

BD: What’s next for you?

SM: I’m burning through the first draft of my next book, which is going to be such a clusterfuck to edit, but I’m definitely excited to get back to it every day. It’s that feeling that comes over you, this fugue, where the people in your book are as real and vital to you as anything in your own life. Also, I optioned Ohio to MGM and am hoping to adapt it into a limited series, but until you’re sitting down with the popcorn watching the first episode, you’ve got to keep your expectations with Hollywood in check. It’s just so remarkable to me that I actually made it to a place where I’m writing and living my life and waking up every morning to go play in the sandbox. I don’t want to take even a moment of it for granted.