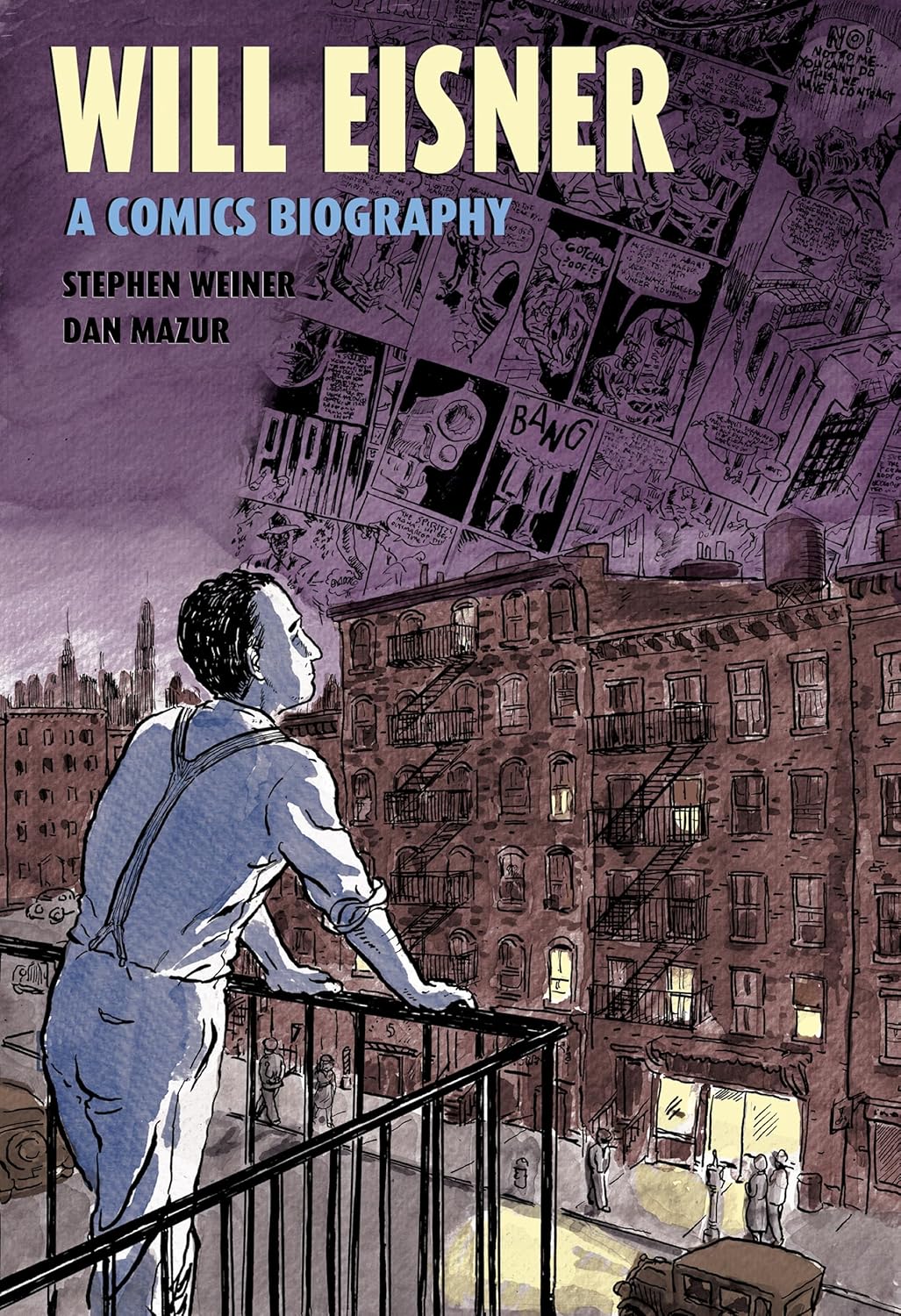

Stephen Weiner and Dan Mazur

NBM ($29.99)

by Paul Buhle

It is perhaps not so surprising to learn that the real story of a hugely popular 20th-century comic art form has slipped into a seemingly distant past, even as a densely theoretical, university-based comics scholarship emerges. Even now, the medium’s foremost artists are mostly viewed as visual entertainers; their real-life stories, from their studios to their private lives, gather little of the attention given to artists by the museum world.

Will Eisner is surely a case in point. Creator of “The Spirit,” Eisner reset the visual standard with his cinematic innovations and snappy plot lines. An innovator who ran his own studio, he founded a unique comic-within-the-newspaper that reached millions of news-hungry readers of the 1940s—among them young Jules Feiffer and Wally Wood, employees of Eisner’s studio and future comic stars in their own right. Eisner was a businessman and an artist; he had no real successors in the press or the comic book industry.

As rendered by the writer-artist team of Stephen Weiner and Dan Mazur, Will Eisner: A Comics Biography seeks to wrap this story around the life of a fanatically hard-working youngster who evolves with the times. Much of the wider context of comics, as both an art and a business, has been squeezed down in the telling, but we see here at close range the real misery of the comic artist, fighting poverty sans respect or sentimentalization of the historic suffering-artist kind. The book closes with an older Eisner making a startling comics comeback, evidently shifting from a dog-eat-dog individualism toward a better understanding of the world.

To return to the beginnings: Eisner’s immigrant father, a sometime set-designer in pre-World War II Europe, is shown to experience all the frustrations of life in the impoverished Bronx and Brooklyn of the 1920s and ’30s. Hounded by unemployment and ethnic prejudice, the family moves repeatedly. By 1927, ten-year-old Will is already thinking about comics as a way to make a living and escape the household where the patriarch is a demoralizing failure.

Newspaper comics, created for semi-literate urban audiences of the 1890s and full of humorous one-liners, had become a family-oriented genre by the 1920s. Pulp magazines, with lurid fiction leaning toward pornography, offered a different angle on popular culture, and from this seemingly unlikely quarter, the comic book publishing world emerged. From the first glimpses of Superman, created by two Cleveland counterparts to Eisner, boys across the country raced to the newsstands with dimes for vicarious fulfillment. Meanwhile, Eisner’s acquaintance and rival Bob Kane was in the process of inventing a less-supernatural, visually darker hero: Batman.

Some of the most agonized pages of Will Eisner reflect the artist’s desperate effort to make a living at the lowest level of comics, pulling all-nighters to write and draw strips himself to fulfill pulp production quotas. In the process, we are shown the creation/production process, and reminded that still-young Will invented “Sheena, Queen of the Jungle”—she has never quite left popular culture—as a result. He is already managing a team of creators at the age of twenty-three when he comes up with The Spirit.

Obviously handsome, dashing, and a modern hero, The Spirit wears an eye-covering mask; he has a secret identity. But the important thing is the comic page-and-panel world that he moves through. Arguably, Eisner’s creation changed what is often called the “visual vocabulary” of comics by shifting the perspective of the viewer from page to page, relying heavily upon suspense, slapstick humor, and an occasional serving of cheesecake in the long and shapely legs of dames who turn out, often enough, to be spies or criminal accomplices. In ways that neither comic books nor comic strips could manage, Eisner’s micro-comic, inserted into Saturday newspapers, told a coherent and entertaining story to an audience more grown-up than the newsstand buyers, and The Spirit was a hit.

Eisner was drafted when the war came, and during his service, he created educational comics within the Army, unknowingly preparing for his post-Spirit days. Meanwhile, the insert continued; by 1945, he had learned to turn over more and more of the weekly grind to his staff. Beyond comics, noir films filled movie screens between 1946 and 1950; Eisner, a patriot and mostly humorous anti-Russian Cold Warrior, would not have guessed how many of the best noir films were written by Communists or near-Communists who saw postwar America through a glass darkly. His darkness was not theirs, exactly: He did not blame the rich and powerful, nor did the Spirit go after racists and anti-Semites, as some leading films dared to do. Eisner’s female characters, good or (more interestingly) bad, lacked any real volition, and the Spirit’s Black assistant was a throwback to racial stereotypes shifting for the better during wartime. But the darkness that artists of all kinds felt after the war years actually improved Eisner’s art, as it made him take more chances with narratives even as he drew a phase of his life to a close.

In 1950, Eisner, then a prosperous suburban homeowner and happily married businessman, launched a company that promised educational, instructive comics. The Army was immediately his best, though by no means his only, client. He closed out The Spirit officially in 1952 and seemed to have abandoned popular entertainment, the telling of fictional stories through comic art.

Only in the last few pages of the book do we learn that underground comix publisher Denis Kitchen persuaded Eisner to return to the medium decades later, first through reprints, then a brief Spirit revival, and then onward to new graphic novels. During the 1980s and ’90s, Eisner turned out almost two dozen books, from graphic art instruction to novelistic narratives of many kinds. In 1988, the Eisner Award, blessed annually at the San Diego Comic-Con, made clear his lasting fame. (I am happy to have shared one of these awards for The Art of Harvey Kurtzman [Abrams, 2009], Eisner’s younger friend of the 1950s and later.)

Writer Stephen Weiner and artist Dan Mazur have inevitably skipped over large chunks of comics history for a compelling bildungsroman of economic, family, and personal drama. Businessmen made a lot of money, but artists experienced extreme exploitation. Among his personal or moral weaknesses, Eisner did not—apparently could not—see the need for unions of comics workers, from efforts in the 1930s to a heroic if failed struggle during the early 1950s. In later years—as he was seeking to make amends on racial matters—he even began to see the wrongs of the Vietnam War, though he never quite grappled with the Israeli/Jewish dilemma of being at the wrong end of a particular suffering humanity. Eisner was always the consummate artist—and in that regard, this book captures his best self.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Fall 2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025