Glenn Ingersoll

AC Books ($24)

by Mike Bove

How does a book become a book? Do authors have actual creative agency, or are they instruments of unseen forces, translators of an unspoken language? These questions are the beating heart of Glenn Ingersoll’s Autobiography of a Book, an inventive, fun, and wildly philosophical reading experience.

In the Romantic era, artists and writers rediscovered an ancient musical instrument played by invisible currents: the Aeolian harp. Named for the Greek god of wind, it’s essentially a set of strings fixed to a long hollow box placed before an open window or on a flat surface outdoors; the strings convert wind energy into sound, haunting and ethereal. The Romantics loved the Aeolian harp as a metaphor for how the artist is simply a tool of nature, a way for natural forces to make themselves known.

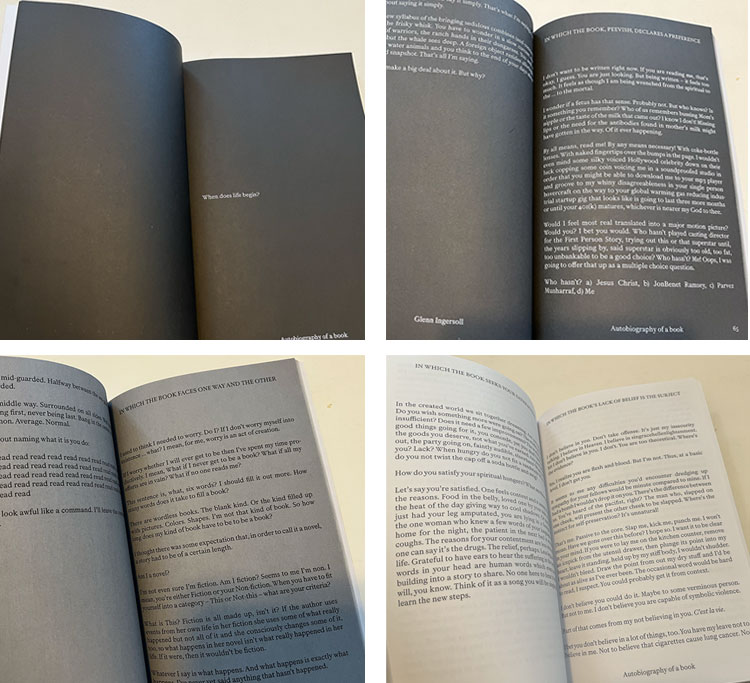

Autobiography of a Book begins with a question followed immediately by an answer: “When does life begin? Life begins with an utterance. A word.” It is not the first nor the last question the book asks its reader, and gradually it becomes clear that Book itself, the protagonist and narrative voice, is asking because it really wants to know: What does it mean to exist, and how is life lived? “When did you know you existed? Does a cat know it exists? Does an elephant? What about a monk or a nun?”

This investigation of existence is often playful, framed with disarming humor and wit. It might be tempting to dismiss Book’s continual self-questioning as naive navel-gazing, but to do so would be to miss Ingersoll’s ability to echo the unconscious questioning that takes place in the human mind at any given moment. We are constantly at play with questions, seeking answers we may never get: How did I get here, what do I do next, what am I for? Book’s voice pivots from sarcasm to humility and authority and back again, proclaiming, “Reality is whatever I say it is.” We can’t deny that in so many ways our reality is a construct of our bouncy, confused minds, constantly filtering stimuli and making sounds out of the breeze.

Fun isn’t always part of the process of being. Sometimes it’s uncomfortable, as Book freely admits: “I don’t want to be written right now. If you are reading me, that’s okay, I guess. You are just looking. But being written—it feels too much. It feels as though I am being wrenched from the spiritual to the . . . to the mortal.” One of Ingersoll’s primary narrative devices is Book’s vacillation. In one section, Book might be resentful of the reader, of being thrust into existence; in the next, Book might fawn over the reader’s benevolence: “it is only due to your unexpected mercy, it is only because of your infinite compassion, the grace you grant with a blink of your eye. It is for you I live. Without you I am nothing. Nothing!”

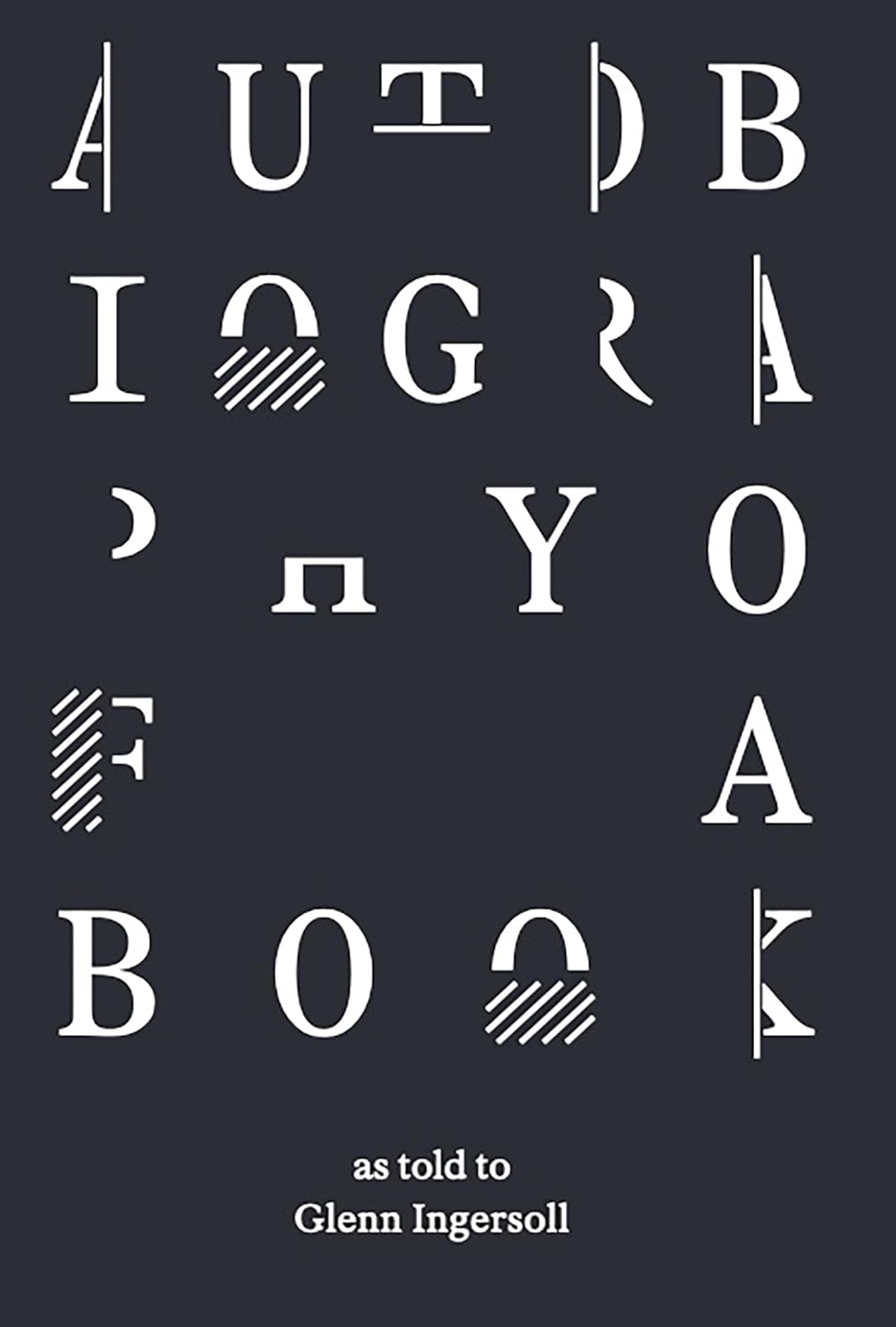

The visual design of the book also deserves attention. Autobiography of a Book begins with bright white type on black pages that slowly lighten to gray, mirroring the darkness of non-existence from which Book gradually emerges. About halfway through, the pages are light enough to warrant a shift from white type to black. Appropriately enough, Book’s first works in black type are “I am alive.” From here the pages continue to lighten, and by the time the book concludes, they are fully white, signaling Book’s achievement of existence, total and complete.

The visual design of the book also deserves attention. Autobiography of a Book begins with bright white type on black pages that slowly lighten to gray, mirroring the darkness of non-existence from which Book gradually emerges. About halfway through, the pages are light enough to warrant a shift from white type to black. Appropriately enough, Book’s first works in black type are “I am alive.” From here the pages continue to lighten, and by the time the book concludes, they are fully white, signaling Book’s achievement of existence, total and complete.

Just as the Romantics saw themselves as Aeolian harps, translating the vibrations of nature into poems and paintings, so too does Ingersoll harness the invisible forces residing within an author. The result is Book, who cajoles the reader into offering it life—for just as music needs a listener to hear it, so too does Book need a reader to read it. With Autobiography of a Book, Ingersoll invites the reader into a truly collaborative thought exercise and makes it both fulfilling and fun.

Rain Taxi Online Edition Winter 2024-2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025