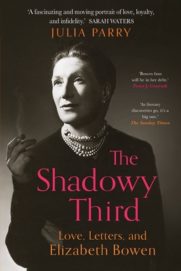

Love, Letters, and Elizabeth Bowen

Love, Letters, and Elizabeth Bowen

Julia Parry

Duckworth Books ($24.95)

by Elizabeth Smith

A box of old love letters discovered in an attic is both the premise of Elizabeth Bowen’s ethereal 1955 novel A World of Love and the real-life inheritance of the author of The Shadowy Third, Julia Parry. During the first decade of Bowen’s own marriage, Parry’s grandfather Humphrey House (who was then a young academic) had an affair with the Anglo-Irish writer. Previously unpublished, the letters Parry found chart the arc of the affair from 1930s Oxford through war-torn London. With Bowen currently enjoying a much-deserved re-examination, The Shadowy Third is cannily timed; a paper treasure trove, it includes letters between House and Bowen as well as House’s wife Madeleine, offering a snapshot of a bygone era in which letter writing was the primary form of communication.

Bowen, born in the twilight of the Protestant Ascendancy, called herself a writer first and woman second. A hostess par excellence, she translated her love of life into exquisite prose. In addition to House, her lovers also included the Irish writer Seán Ó Faoláin and Canadian diplomat Charles Ritchie; these dalliances from her virtually chaste marriage provided endless material for her art. Yet the story Parry tells in her book is curiously bloodless, and despite the salacious revelation that Bowen lost her virginity to House (almost ten years after her own wedding night), the latter comes across as an unconvincing lover, a weak man who wrote to his wife before they wed, “I cannot cure myself, even now our marriage is settled, of violent and casual physical attraction to all kinds of women.” In family lore House was eventually forced to escape the clutches of Bowen by fleeing to India, where he learned Bengali and translated poetry, among other desultory end-of-the-Raj jobs. Bowen, meanwhile, had already begun a flirtation with the American poet May Sarton.

Under Parry’s hand, the three main players are spotlit and shadowed by turns. The affair proceeds across England and Ireland, and we see Elizabeth inviting Humphrey (and occasionally, Madeleine) into her sophisticated world of writers, intellectuals, and aristocrats. It is the author herself who is least shadowy. Her journey through the letters, taking her from London to India, the U.S., and Ireland, is studded with vignettes of her family, created through supposition and invention. Like Bowen, whose war effort included reporting to the British authorities on the feelings prevalent in neutral Ireland, Parry calls herself “a spy, an interceptor . . . I have a metaphorical red crayon and pair of scissors,” and she echoes her grandfather’s delight in the “privilege in the discovery of unknown papers.”

Parry wields her scissors heavily, doling out Bowen’s beautiful words with a tight fist, one eye always on her family’s reputation. When we are allowed a glimpse of the prose, however, it is a lovely treat indeed. In a rare full letter, Elizabeth describes “A young woman in a sky-blue dress who walk[ed] past along the bank, by a row of poplars as we were having tea, like a Renoir figure,” and writes even more blissfully of how “Those untrodden-looking valleys slipping liquidly past in the evening light were a dream . . .” Ultimately, Parry’s story is frustrating, however, and her reticence to give Bowen voice begs the question: Who is the “shadowy third” in the triangle?