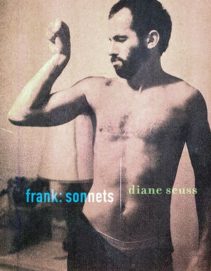

Diane Seuss

Diane Seuss

Graywolf Press ($16)

by Meryl Natchez

Diane Seuss’s fifth book of poems, frank: sonnets, provides fresh imagery, calls out the male icons of the ’70s and early ’80s New York scene, and directly grapples with loneliness, addiction, abortion, and death. The language is often startling, the incidents pried open for the reader to enter and observe. The overall arc of the book is memoir: stories of grief, of questing, of trying to make sense of a complex life. These poems appear in the order written, with long sequences about Seuss’s father, her lovers, her exploits and failures, and the death of a close friend.

One of the most moving sections is at the center of the book, detailing the years of her son’s struggle with addiction. Seuss manages to telescope pain and compassion:

and I was such a fool, believing in fruition, stuck inside the fairy

tale of resurrection, even stars, he said, are trying to get by and then

he used for ten more years and bankruptcy and where’s the melody

to remedy the melody, the remedy to remedy the remedy?

Seuss also has a gift for imagery, which enhances the work, raising it above pure memoir. Her father’s illness and death as well as the death of other men in her life are explored with amazing specificity of memory:

at my father’s I was small and sat on the floor of the hearse,

people said don’t be sad, there was macaroni afterward, I liked macaroni . . .

Another intriguing section of the book deals with the author’s years as part of the New York art and poetry scene:

Richard Hell,

Lou Reed, Basquiat, Warhol, Burroughs Kenneth Koch,

and it all left me feeling invisible or fucked, fucked

sideways, fucked by a john who stiffs you on your fee

and doesn’t leave a tip . . .

This indictment is direct, while also acknowledging how hard it is to escape the glamor of these mythic figures. In settings closer to home, too, Seuss balances the longing for love and compassion against the complications it engenders; this comes across vividly in the poems about her son and those about her friend Mikel, who died of AIDS.

Perhaps most importantly, Seuss has a way of confronting her own fears and failings that draws us in. Reading through the varied trauma of these memoiristic poems is reminiscent of Czesław Miłosz’s The Witness of Poetry, in which he notes how writing about past events allows one to record them but also to distance oneself from the wreckage.

Some readers might quibble with Seuss designating these poems as “sonnets”; they may be fourteen lines, but they don’t break new ground as to what can be done with or included in the form. Nonetheless, frank: sonnets is worth reading for its feistiness and unashamed transgression. It delivers a life—flawed, raw, and multi-hued—and whether or not the poems that tell it are sonnets, it’s a life worth exploring.