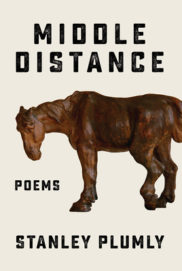

Stanley Plumly

Stanley Plumly

W.W. Norton & Company ($26.95)

by Walter Holland

Stanley Plumly, who died in April of 2019, was often regarded as “the most English of American poets,” or even “the American Keats.” This high praise was borne out by his lyric melancholy, attentiveness to nature, and personal introspection characteristic of Romantic poetry.

Middle Distance, Plumly’s final book, is a coda of sorts to the poet’s vast and creative career. Completed two months before his death, the manuscript was shepherded posthumously to print by David Baker, Michael Collier, and Margaret Forian Plumly. The opening poem, “White Rhino,” is representative; in it, Plumly presents himself as facing mortality and by extension extinction—much like the last known northern white rhinoceros that died in Kenya in 2018. As is so common in Plumly, animals and birds haunt his world and are used symbolically as vehicles to convey complex reflections on human behavior, emotions, and loneliness. “Old age is a disguise, the hard outside, the soft inside,” Plumly writes. Then he poignantly observes:

. . . I hardly recognize myself except in

memory, except when the mind overwhelms the lonely

body. So I lumber on, part of me empty, part of me

filled with longing—I’m half-blind but see what I see,the half sun on the hill. How long a life is too long,

as I take my time from here to there, the one world

dried-out distances, nose, horn, my great head lifted down,

the tonnage of my heart almost more than I can carry.

This is classic Plumly, one that carries fraught human emotions on passing time and death. Frequently he deals with the ephemeral yet eternal sense of nature along with the burden of existential emptiness. These ideas are seamlessly juxtaposed with the revivifying force of memory along with memory’s power to create myth and haunting sublimity out of everyday gestures. Like Keats and the other British Romantics, Plumly’s poems revolve around the intimation of immortality, and the powerful longing in the face of mortality. Memory is the only salve for the harsh destructive present, especially the assault on nature by mankind. Memory as well is an evolutionary function of biological survival, especially if we are doubters of the afterlife. It serves as both curse and adaptation, our only link with the concept of the eternal.

In a wonderful interview with Plumly by Peter Davison in the January 8, 2003 Atlantic Unbound, Plumly makes several statements that get to the core of his views on writing poetry and Keats:

When Keats speaks of "the holiness of the heart's affections" and links such absolutes as the imagination, beauty, and truth, when he questions life in the terms of art, it lifts the activity of poetry to some ultimate purpose. Simply put, poetry is the thing in my life that has made the most sense and remained the one constant.

Another part of the influence is the nature of Keats's text itself . . . the richness, the density of his poems, the way in which language is always in multiple places at once—generous, physical, and most of all quick. I think it's the speed of his connections that makes him the most modern of the Romantics; that, and his sense that the poem is its own world or—as he puts it—"that which is creative must create itself."

As does Keats, Plumly looks at nature as our originary teacher. All the imponderable mysteries and intractable questions of beauty, art, and human existence can be found there. It is our truest “objective correlative” and yet through evolution we have left nature behind and suffer as a result alienation. Plumly goes on to say:

My sympathy, obviously, is with nature, while at the same time feeling separate. Our separateness is one of our basic themes in poetry. I sometimes think that the closer you feel with the natural world the closer you can be with other people. This may be Wordsworthian, but it's true. Nature is a teacher. The more we, as a culture, alienate ourselves from it the more alien we become.

A Plumly poem is visually intense and evocative, cinematic in its attention to detail and gesture, and sensual in its play of sight and sound. A single, vividly described scene or image usually pulls us into a ruminative meditation on loss, love, or longing; this leads to an end line that presents a strange epiphany. More commonly than not Plumly ends his poems with a volta, or “turn,” usually placed at the end of the first octave in the classic sonnet. The volta functions as a dramatic change in thought, emotion, and rhetoric, leading to the resolution of the question posed at the poem’s beginning. It affirms closure. Plumly, however, attenuates or interrupts this epiphany by frequently shifting the poem into a liminal state of suspension, leaving us with an image which suggests transcendence but also doubt. This technique achieves a haunting quality as discordant as an off-rhyme. Plumly comments:

I prefer an attenuated narrative, an interrupted, delayed narrative. Narrative, I believe, is indispensable to the lyric; it's what makes it move instead of spinning its wheels. It's what motivates the poem to turn, to go on, continue, rather than simply returning, over and over. Narrative provides the major formal tension to the lyric stability in a poem. It's what causes the line to turn the corner. What is a "story" anyway but someone speaking, drawing a line that assumes a shape, a shape that becomes a figure. But a line too straight is uninteresting; that's why the "narrative" must break, bend, meander; that's why indirection and juxtaposition are so important to maintaining the intensity, the surprise all art needs to keep the music going, the line moving. It's the strength Keats at his best that he depends, even in the odes, on a narrative base-line; it's what brings his lyric drama to life.

This “break,” “bend,” and “meander,” this “indirection and juxtaposition,” are clearly important to Plumly. It’s what leads to his frequent erratic rhetorical turns at the end of his poems. A wonderful example of this is found in Middle Distance with “Planet.” The poem meanders through a narrative of Plumly’s youth, arriving later at its central image: a polio-stricken “true angel” from his school who has been placed in an iron lung as a last resort to save her. This girl, “whose beauty was enough” for the young Plumly, is described as a romantic focus of Plumly’s for many years: “For too many years I dreamed of her or someone like her / at the far end of a platform or at a window on a train/ slowly coming in, her face half profiled in the late evening sunlight / the way, in the way of recurring dreams, we fall in love.” This unrequited love, this dream romance, becomes an image of ephemeral beauty, death, and time—and holds as well a sense of the “separateness” in human life, where spiritual and idealistic absolutes are suspicious and insupportable in the physical world. The poem’s closing offers a series of rhetorical questions and juxtapositions of contrary thoughts:

. . . and then a day it happens,

and you can see in the light blue marbling of her eyes how this

was meant to be, except it wasn’t, it was dreaming of another kind,

once the closing dark has subtracted everything—

was she beautiful, lying there, nineteen fifty-one,

dying in ways that were invisible?—

and what is this loneliness we long for in that someone

no one else can be, who lives or dies, depending,

but who was there, whatever the moment was?

The attenuated phrasings that bring us to a surprisingly inconclusive and anticlimactic question at the poem’s end only underscore Plumly’s doubt and the illusory effects of memory. The girl never became his love and yet her memory has stayed with him all those years, resurrected by transcendent feeling.

Plumly often embraces Keats’s idea of “negative capability.” At the start of “Planet,” he paradoxically muses over death and dying:

There is the thought that when you go you take it all with you,

whatever all is: dying as either an ontological condition

of past-caring or a heartsick feeling that none of it mattered,

not the friend forgotten nor the friend denied,

not the child that didn’t happen

nor the years lost nor the day you walked away,

not the century since nor the days-on-end of starting out the day,

not the thinking and rethinking what you thought—

now that your body is no longer yours nor even a body

in death’s fantasy but a look-alike of makeup and sweet fluids, . . .

Using antithesis in these contrasting and opposing statements, along with anaphora with the repeated inverted, negative adverbials, Plumly embodies Keats’s rhetorical sense of uncertainty and doubt. Notable are the second and third stanzas where Plumly presents his vision of artistic beauty, namely Mary Neal’s angelic presence, her marble blue eyes and luminous face suffused by evening sunlight. Plumly begins to doubt, however, her true beauty as opposed to how his mind makes her a symbol of beauty’s ephemeral nature. He speaks of “the closing dark” of death which he knows has “subtracted everything” of her presence in the material world. In the end, Plumly wonders if his intellectual confusion and uncertainty are more a function of his mythologizing mind and memory. Plumly offers no certainty here, but seems to accept this “half-knowledge.”

Plumly drew his complex sensibility from many of the great Romantic painters. He exhibits this in his attention to the visual drama of sunlight and dark, color and light, day and night, clear weather or storminess. His descriptions offer a range of silhouettes and tonalities. Constable, Turner, Whistler: these men gazed longingly on nature or the human figure, dwelling in the realms of perspective, distance, and light to express varied emotions. Vanitas motifs of dead trees or brief intimate images of youth or old age unaware along with sunny skies or seascapes caught on the edge of stormy shadows were common features in Romantic painting. Romantic artists were adept at depicting the liminal suspension of momentary actions; time, distance, and contemplation attended their visions of nature, which they often used symbolically to represent the transient and finite nature of life. Plumly applied these themes to his own American life experience: family memories, the landscape of Ohio, the forests he explores and the cities he visits. Light lends his recollected past, his fond archetypal images, an immortality which defies earthly temporality. These moments in time are recalled with photographic verisimilitude and take on iconic transcendence.

Middle Distance displays all the powers of Plumly’s gift for lyric description; a reader new to Plumly’s work will find in this final book a glimpse at his luminous, visionary skill. “Winter Evening” is a perfect primer for his technical mastery:

Give it another month from now, though why wait

on ceremony, the winter light this early late November

evening the soft blue bruise of where the heart has

thinned the blood—and cold, so cold, the kind of clarity

a star will clarify before the sky is full of them, the blue

gone for good. . . .

The musicality of Plumly, his total command of the poem’s flow and figuration, is self-evident. As Plumly writes at the close of his Atlantic Unbound interview, he believes in “meter at the service of speech, self-dialogue, if you will.” Further, he admits that his “prosodic mantra” has always been one of “assonance, consonance, and surprise” as well as “hearing and seeing in a poem, naming and bringing the thing—the image, the object—to life . . . Shut your eyes and your ears will be your eyes, cover your ears and your eyes will hear. Language makes the senses one.”

Middle Distance is heartfelt and tragic, dealing with the poet’s experiences in the hospital toward the end of his life, and with the sad scenes of illness and boredom. He suffers an episode of cardiac arrest and sudden unconsciousness. After his being revived this becomes a deliberation on the oblivion of death, its failure in providing vivid dreams or transcendent revelations. While receiving chemo in “The Ward,” Plumly ponders his fellow patients and gives a glimpse of the banality of modern medicine and the tedium of dying. Again his parents return as potent figureheads and symbols of a vanished America. Memories of fellow poets, travels abroad, are joined with longer pieces that are akin to diary notes, most of which cover the subject of earlier books. In a beautiful meditation on the painter Constable along with two or three ekphrastic poems, Plumly revisits the British Romantic master painters he so richly cherished and studied.

Some poems here are paler replicas of already plumbed depths and covered territory. Plumly revisits many of the primary touchstones that have long acted as imaginative templates, archetypical motifs throughout his career. But Middle Distance is well worth the journey. A first-time reader should investigate Plumly’s two late masterworks, both also published by W. W. Norton & Company: Orphan Hours (2013) and Against Sunset (2017). To the end he persists in detailing and recapturing the Keatsian pathos with which he so identified, recording the sensations and landscapes of life—including its mysteries and transcendent qualities of place and time.