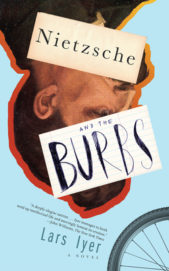

Lars Iyer

Lars Iyer

Melville House ($16.99)

by Scott F. Parker

- Nietzsche calls to the fiction writer, the mystique of his name inclining some to invoke it (When Nietzsche Wept, Nietzsche’s Kisses) or its associations (the film The Turin Horse, The Will to Power by Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche) in their titles. Into this company, Lars Iyer throws his Nietzsche and the Burbs.

- The economy of Nietzsche and the Burbs: book title, name of band formed by main characters, plot summary, all in one.

- Style is essence here. Minimal narration, more like a play than a novel. A few words to establish setting, then right into dialogue.

- So much dialogue, much of it funny, all of it smart. Still, it is possible to spend too much time listening in on teenagers—even clever ones—talk and talk and talk.

- I remember these characters from high school and how they appeared from where I was standing: culturally astute; dexterous with reference, allusion, and wit; brilliant and bored; cynical and sad. I didn’t hang out with them then, and I don’t want to hang out with them now. They can be impressive and entertaining, but they are simply too exhausting.

- Nietzsche and the Burbs is a kind of cinéma vérité too true for its own good. Like its characters, it’s a bit too clever, too showy, too ironic, too cerebral. It’s like a Linklater film without his tender delight in the stuff of life (Linklater is nothing if not an anti-nihilist).

- All theory, no action, the book knows what it needs: “Maybe we’ve got to play against our cynicism,” one character says. “Break through to something.” Something, yes, but what?

- “We need vocals . . . . We need someone to lead the songs. Some we can follow.” Nietzsche, of course. Through his character in the novel’s world as through his prose in our world, Nietzsche animates. His readers will recognize him here by more than name; Iyer’s Nietzsche taps the intensity, brilliance, and dynamism of his namesake. When we meet him, he is renouncing the assumptions of the bourgeoisie. His teacher is incredulous: “You want to get rid of the economy? What would we have in its place?” His answer, naturally, is “Life.” If you are stimulated by Nietzsche the philosopher, you’ll be stimulated by Nietzsche the suburban teenager who threatens the inertia of the suburbs and his peers whenever he speaks (or sings), which is not frequently.

- The book, like the band, is lost without its frontman. Before anyone can escape the nihilism they’re all mired in, Nietzsche—and this is just one of many playful parallels with the philosopher’s biography—has a breakdown and comes to be under the care of his mother and evil sister.

- But nihilism. Everyone in the book keeps saying it. Nihilism. “Sounds interesting,” the narrator says. “It isn’t interesting. It’s devastating,” Nietzsche responds.

- It’s only right that the young Nietzsche is cast as the philosopher of the suburbs. If you can overcome nihilism in the suburbs, you can overcome it anywhere. Therefore, for one to really live, to thrive, to become, to overcome, only the suburbs will do. But if even Nietzsche can’t escape nihilism, what hope is there for a band of ironically detached teenagers? He issues his assessment of “devastating” on page eleven. In the 300-plus pages that follow, none of his peers take his claim to heart. What hope is there for readers?

- The book is mired in its condition. Whereas you leave an encounter with the philosopher Nietzsche feeling—feeling—his effects, you put down Nietzsche and the Burbs with a wry smile (if you like it) or eyes hurt from rolling (if you don’t). Either way, all the action is in your head, where nihilism thrives.