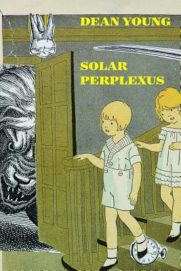

Dean Young

Dean Young

Copper Canyon Press ($22)

by Thomas Moody

I don’t know what people mean

by reality.

Is it the ocean

which I’ve always loved

no matter its chitinous claws

or the sky everything falls through

or those scary-ass mites

that live on our eyelids

or the rain of diamonds on Saturn?

These are the opening lines of Solar Perplexus, Dean Young’s latest collection of poetry, his sixteenth. They are from a poem ironically titled “Reality,” a state of things that anyone familiar with Young’s poetry over the past three decades knows is rarely described (the ocean’s “chitinous claws”), but somehow, through a web of absurdist avenues, is always encountered, represented, and uncannily felt. No matter how surreal the images Young conjures are, or how unexpected their associations, they are always rooted to an emotional truth, so that in his poetry we recognize both the scattered external world around us, and our equally discordant internal lives. Reality, as the poem suggests, is not fixed and objective; it shifts, disassembles and reassembles, always elusive but ever present (something we have sadly become all too aware of in the past three or so years). “Whatever it is,” Young continues, as if to confirm the trajectory of the collection, “I’m sure I’ve tried to avoid it.”

But there are, of course, agents of reality that cannot be avoided, and although all the hallmarks of Young’s singular style are on display in Solar Perplexus—his hyper-paced collage of disparate images laced with pop-culture and literary references, not to mention his wit, irony, and pathos—the tone of these poems is, on the whole, less wry than previous collections, and more candid, both somber and ecstatic. In his third book following a heart-transplant in 2011, after suffering for years from congenital heart failure, Young muses on the body, its temporality, vulnerability, and the estrangement we can feel from our very own organs. In “My Collage Life,” Young acknowledges that his body itself has become, through the process of his heart transplant, mimetic of his poetic style: “So after being chopped apart, / sewn back together from mostly / the same stuff, some 70s prog rock / still sticking out, some Kafka fluff, / how’s it feel to still be alive where you are?” In “Flight Path,” the body is “a shoe box, precious tanglement / of kelp, china doll-head fit perfectly / in the palm crushing it or not.” In “Corpse Pose,” which details the fraction of time during the transplant the poet was a body without a heart, Young comically speaks to a Cartesian dualism: “My body hates my soul, how / it stays so skinny thriving on air, / never hungover, never hit with fist / or restraining order, defying / that old dualism, flirting at the party / like it's never been spurned.”

Solar Perplexus also confronts death, both Young’s own precarious adjacency to it, and the death of his contemporary and friend, the acclaimed Slovenian poet Tomaž Šalamun: “I don’t know if Tomaž / was scattered into the Hippocrene / or baked into a heavy, seedy peasant bread / to break among his young acolytes / like wedding cake but everyone says / his death mask smiles.” Young’s poetry contends, however, that while there may be no physical means to avoid existence’s coarse realities, be they illness, death, or even turgid English departments (“My studies in human potential / collapsed when I joined an English department” he writes in “The Institutionalization of American Poetry”), they can at the least be palliated, if not entirely eradicated, by a genuine engagement with one’s imagination. For Young, the imagination is a means to salvation, not puerile but sacred. It is through the imagination, via poetry (“All poetry is a form of hope” opens one poem), that we reach a place of empathy, excitement, and equanimity of a kind: “The skull / permanently smiles so what / is there to worry about.”

Young is Whitmanic in his appreciation of the imagination (there is a sly reference to Whitman in the lines “and there’s no such thing as death, / just darkness / and darkness never hurt anyone”), often challenging the reader to embrace their own: “Friend, lift yourself from / your webby substrate. / Inoculate the daffodils! / Inculcate daffodils! / Do fucking something with daffodils!” He also seemingly asks for approval of his poetry in real time: “Knock-knock joke in ICU. / No one knows who’s there / so keep guessing. How about / a burning scarecrow taking blood donations?”

These last lines are from “Pep Talk in a Crater,” which includes all of the finest elements of a Dean Young poem. Here are a few lines:

Often I too have been chased barefoot

by I know not what. Often a meadow

struggles to mention itself. Thus

someone can start out a column of flames

and be moth-dust by afternoon.

Thus another can collapse in on herself

like a neuron star. All we know for sure

is Mozart took a lot of hammering

and all those trees had to be screwed in.

Once the little green wings are smashed

from the wedding vessels, it’s okay

to feel like you’re watching your own murder

with a butterscotch in your mouth,

like how laughing makes the coffin

easier to carry, the usual rueful decorums

masking the want-my-mommy,

this-ain’t-my-planet wail.

There is a rush of excitement here, in part because the poem is alive, as if it has managed to retain the raw materials of language itself (as is Young’s wish for his poetry, stated in his brilliant essay-length book The Art of Recklessness, required reading for any poet looking for validation of their vocation). Whole universes of thought are packed into it through a propulsion of words, and while the manic shifts in imagery permit little time to reflect on any one in particular—despite whether they demand our reflection (“it’s okay / to feel like you’re watching your own murder”)—they build upon one another without erasure, so that a swarm of shadow lines and ghost images trail throughout the poem, sometimes to return, sometimes merely to hover in our subconscious. This deft construct of images allows for Young’s poems to be greater than the sum of their parts—the various and conflicting sensations that both the process of collage and its aggregate arouse in the reader are far more powerful than the sensations caused by any individual image itself. It is this achievement that often separates Young’s poetry from those that it influences.

In “Dance Event”, the most affecting poem in Solar Perplexus, however, Young strips the words of their propulsion, breaking them down into a series of fragmentary utterances; the language devolves so as to arrive at the essential message. The poem ends:

Simple test:

Approach a strawberry.

A pulse is kid stuff.

Dance in live ash with feathers

through your earlobes.

Converse with a sapling.

Walk cloud.

Macerate in Cointreau.

Estivate and call home.

Feed a fever fever.

Cradle dawn.

Love everyone.

The last instruction is also a directive to the imagination, for love relies on empathy, and empathy can only be achieved through imagining the condition of the other. “The heart has nothing / to do with it. The heart has everything / to do with it,” Young writes in “My Process.” Are we to take these lines, due to Young’s medical history, to be referring to the literal heart? Sure. But they are also concerned with the metaphorical heart, just as fragile but equally vital to our survival. In an era marked by a near bankruptcy in empathy, where realities are fractured and decidedly antagonistic, a rich imagination can provide a needed corrective—and there is no greater arena for the imagination to be celebrated than poetry, Solar Perplexus affirms, where “The blood may be fake / but the bleeding’s not.”