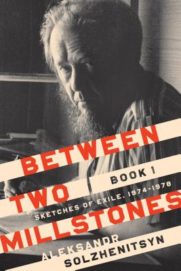

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

translated by Peter Constantine

University of Notre Dame Press ($35)

by Jeff Bursey

The Publishers Weekly review of Between Two Millstones calls its author “a onetime giant in the world of letters.” There are indeed few figures like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008); among his major achievements, the three-volume The Gulag Archipelago revealed to the entire world the extent and purpose of the USSR’s penal system, and the novel cycle The Red Wheel revisits the origins of the Russian Revolution. August 1914 and November 1916, the first two books in this mammoth and compelling synthesis of disparate material, were recently succeeded in English translation by the first volume of March 1917, with three more volumes to follow, and the cycle will conclude with the two-volume April 1917.

Controversial in life and in death, this “onetime giant” doesn’t attract readers now the way he did in the 1970s. While we can’t hold dead writers responsible for the company that keeps them, invariably we look askance at them when we see them held up by those whose philosophy or ideology we don’t share. If someone unfamiliar with Solzhenitsyn decided that because conservatives touted him that this meant he was a cranky Orthodox Christian, a fascist, a czarist, or a traditional novelist—and therefore not worth reading—then this would be a lost opportunity to hear a distinct humane voice, like Dostoyevsky or Vollmann or Akhmatova.

Serialized in a Russian journal from 1998 to 2003 and revised by Solzhenitsyn in 2004 and 2008, Between Two Millstones, a memoir newly translated into English, is loosely structured so that two main topics can be covered: his life in Switzerland after he (and eventually his family) is removed from his homeland, and his search for a new place to live so he can work in peace on The Red Wheel and other projects. The former citizen-prisoner (he refers to the USSR as “the whole Great Soviet Prison”) had his life turned upside down by exile and the world’s attention. Though Solzhenitsyn describes what he’s going through with his usual directness, one can only imagine the impact of such a traumatic and abrupt separation, with no known future, from country and kin. He “emerged from a great tumult” within a repressive regime where he had to hide almost everything he did and guard almost everything he said; in an apparently welcoming world, reporters endangered his family while they were still in the USSR by hounding him for pronouncements on international affairs. Cautious, bewildered, and off-balance, Solzhenitsyn made missteps, and he often voices this refrain, with variations: “from the very outset the Western media and I were not to be friends, were not to understand one another.”

The five chapter titles summarize the strain of these first four years even after his reunion with his family: “Untethered”; “Predators and Dupes”; “Another Year Adrift”; “At Five Brooks”; and “Through the Fumes.” Solzhenitsyn felt overwhelmed by sudden fame. In Zurich, where he lived first, any stranger could open the gate of his garden and come knock on his door. Not all wished him well (“the police of two countries had already warned me that I was on the hit list of international terrorists, as I knew well enough; and these terrorists were trained and supplied by the Soviets”), but for a man accustomed to working discreetly and persistently, even the best-intentioned visitor could usurp his writing time—as did invitations, appeals, and messages from abroad that filled his house with mail. Alongside his painful adjustment to Western manners is a presentation of successive errors that started in the USSR and continued for some time after his exile, when he dealt with strangers, translators, publishers, and lawyers. “In the USSR, that hard and unforgiving land, all my steps turned into a series of victories,” Solzhenitsyn writes. “Yet in the West, with its limitless freedom, everything I did (or did not do) ended up in a string of defeats. Did I ever fail to make a mistake here?”

Of great interest to read about are the arguments Solzhenitsyn had with Andrei Sinyavsky and Andrei Sakharov, his suggestion to Vladimir Nabokov on subject matter, the KGB assassination and smear campaigns (also involving his ex-wife), and how he was praised or criticized by Ronald Reagan, Gerald Ford, Henry Kissinger, and Jimmy Carter. The book’s appendix contains letters and other documents that show how such public figures, as well as institutions, wished to honor him, use him for political purposes or, in the case of media outlets, transform his words and actions into stories that could be sober or sensationalist. Solzhenitsyn resists the allurements offered by various people, in part due to a well-honed suspicion of motivations—though as the book amply proves he was not infallible, nor did he think of himself that way. At times he comes across as overbearing, but this is understandable; to survive the carceral environment of the USSR demanded from him, apart from strength of character, a high self-regard and a pugnacious ego. In this first volume of Between Two Millstones (one more is due out next year), Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who spoke out for the many who survived or perished in the camps, tells an engaging tale of his initial exposure to Western ways.