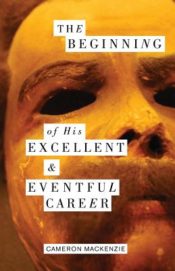

Cameron MacKenzie

Cameron MacKenzie

MadHat Press ($21.95)

by John Wall Barger

The leaves ran along my ears as I moved deeper into the dimness of the rows, and as I ran I heard the shouting of men around me, frightened and desperate to find a crazed killer, a demon boy. . . . The sky then opened simple and blue above me, my horse grazing peacefully in the adjacent field. I saw no man cutting stalks and I saw no man collecting wood and neither was I seen by them. Not ten minutes later I was high on a ridge, my belly flat on the warm stones, looking down at the comedy of the men I had left alive.

The “demon boy” of the passage above is Francisco “Pancho” Villa (1878-1923), long before he becomes the famous Mexican revolutionary, and he is hunting the man who raped his sister. From the first pages of The Beginning of His Excellent and Eventful Career, when the above scene takes place, the reader is struck by Cameron MacKenzie’s dexterity with language. Long serpentine lines embellished with alliteration abound. MacKenzie not only takes pleasure in the music of his lines, but trusts the aural reverie so fully that at times in his novel, as in poetry, sound precedes sense, deliciously. And this music becomes intertwined with the unrelenting violence it describes. For example, listen to the galloping polyphonic prose, the consonance, and the knifelike simile from the line that precedes the ones above: “The remaining gunman panicked and turned, kicking up dirt onto the writhing bodies of his fellows where they clutched at their guts and moaned like calves.” MacKenzie’s use of music can be compared to Ennio Morricone’s score of Once Upon a Time in the West: Both melodies, however sweet on the surface, soon become inextricably linked with the shattered psychology of the characters, or with violence itself.

Judging from this novel, his debut, MacKenzie’s literary forebears include Melville, Hemingway, Faulkner, and Cormac McCarthy: authors who tell a story of America, with enormous scope and music. In particular, the reader hears in MacKenzie some of McCarthy’s old testament King James Bible timbre, slathered with blood and mud. In McCarthy’s books, violence seems to emanate out of nature itself, as in this passage from Blood Meridian: “The sun was just down and to the west lay reefs of bloodred clouds up out of which rose little desert nighthawks like fugitives from some great fire at the earth’s end.” McCarthy’s use of language is both simple and shockingly effective. The savage force within the language itself—as if the “great fire at the earth’s end” were speaking on its own behalf—seems to simultaneously emerge out of and obliterate both the illiterate kid of his tale and everything else it touches.

MacKenzie lets his own illiterate kid, manifested by Villa, speak a first-person version of this desolate poetic tongue. Villa talks with the blood-soaked voice of the land itself. In placing such formal, archaic, wise language (e.g., “The day was high and clean and the sky so depthless a blue as to hint at the pure black which lay in silence at the tip of its vault and to which all of this bent as though it be its imagining or its dream”) in the mouth of a child, MacKenzie is not trying for verisimilitude—he does not want to imitate that child’s voice. And how could he, 150 years later, in another country, in a language other than Spanish? The voice and characterization are not realistic, nor should they be. Rather, the child speaks for the land itself, and the land comprises violence, power, fear. For MacKenzie, as for McCarthy, violence is an inextricable part of human life, and must be faced. Certainly there is no way around it for young Villa. He must deal with the “comedy of the men,” or fall like those around him. It’s worth mentioning that, in this world of male violence, MacKenzie—unlike McCarthy—provides us with a number of powerful female characters, like Señora González, who acts a don and frequently challenges Villa.

The Beginning of His Excellent and Eventful Career is divided into four sections, spanning about twenty-five years, from when Villa is a child until the Mexican Revolution begins in earnest, in 1910. The first two sections describe Villa’s years as a ruthless thief in Durango and Chihuahua. The last two sections describe the slow civilizing of Villa into a politician: as a general, gaining in power, negotiating with leaders like Madero, and fighting in the north against the forces of President Díaz. The structure of the novel is such that Villa seems to be stepping into focus, into the “light,” out of the blur of hearsay and legend.

As the years pass, in the first two sections, we watch the bandito Villa commit atrocious crimes, killing and raping without cause. We ask ourselves, who is Villa, and what does he believe? MacKenzie, to his credit, leaves these questions complicated; he walks us into very dark ethical terrain without reaching for spurious morality or for sentimentality, and lets readers decide for themselves what to think of every scene. For example, a seemingly innocuous episode in which Villa watches his mule slip off a mountain pass, turns out to be telling: “And even as its hooves scraped in agitation on the rocks for purchase its black eyes remained as they were and absent of fear. The animal went on to tumble over the edge and out into the air below us, quite without sound, its pack releasing its baubles and skins as though unfurling some new and horrible shape.” This, we are beginning to realize, is how Villa watches everything: impassively, without bias. MacKenzie excels in such passages, shining a light onto an event which is not in the history books. As well-researched as this historical novel is, the book finds liftoff the further it strays into liminal, non-biographical spaces. The hauntingly intimate details of the mule (“its hooves scraped . . . its black eyes remained as they were”) make us feel, uncomfortably, that we have actually witnessed the event.

We also ask ourselves, “What kind of human being watches a mule fall off a cliff without trying to help it?” Villa later says of himself, “I have never feared a man, nor could I, for no man could know me, for I am beyond men as men would be. I am a new man, newly made by my will, and none may touch me where I lie in my rectitude and strength.” So Villa imagines himself as an Übermensch; a creature of the new Mexico; a missing link between the agrarian farmers of the nineteenth century and the capitalists of our modern age. But it is frightening to think of Villa as “a new man,” since we are unable to really gauge where his morals lie. Is he a nihilist? Our disquiet is well-founded, as we discover, just moments after the mule falls, when Villa murders his best friend, Refugio Alvarado:

I removed my rifle from its holster in the saddle by my thigh and leveled it and fired once into his face. For some time, and I do not know how long, I looked at the space in the air where he had been. His face. I sat my horse and looked at his horse where it stood and I looked into the air. The day stretched out for ten thousand miles, ridge upon ridge and the brown plain beyond turned up like a table that would spill its careful contents upon the floor.

At this point, still in the first section, we’ve been on the fence about Villa. We know that he is a murderer, and that he will later become a figurehead in the Mexican Revolution, but we don’t know for sure if we dislike him. We ask ourselves, “Is he redeemable?” When he kills Refugio, we understand that he is past hope. MacKenzie often pauses after such violent episodes (“I looked at the space in the air where he had been”) to allow a certain silence in, as if inviting us, or daring us, to place ourselves into the scene with our sense of humanity intact. It is bold for a novelist to remove the likeability of the main character—it means we are wading into murky waters—MacKenzie delights in such waters, happily wading in further still.

No character in the book epitomizes ethical murk better than Villa’s enforcer, Rodolfo Fierro. A loyal soldier of the revolution who is actually a psychopath, Fierro emerges as the horrifying “hero” of the second half of the novel. We can read about Fierro’s misdeeds on Wikipedia, but MacKenzie takes us far away from history and uncomfortably close to this lunatic, sculpting a character as weird and riveting as Conrad’s Kurtz or McCarthy’s Judge. Fierro has free reign to act as he likes, as long as he follows Villa’s orders, but becomes increasingly unpredictable and unhinged. He transcends traditional description. A blood-soaked trickster emerges in the form of Fierro, wearing a tattered white suit and speaking with cryptic poignancy (“There are times when the imbecility of others would occlude even the most patient of designs”). In one of the book’s most memorable scenes, Fierro has taken a series of prisoners into the desert to be executed, with a few soldiers. Without warning he orders a soldier to cut off the soldier’s own little finger, lets the prisoners go, and vanishes into the dark. We’re not sure where he’s gone, but days later, he appears before the prisoners:

The man was nude. He was dark. He wore a ragged straw hat and he squatted on his haunches on the flat top of the stump some three feet above the ground, his scrotum resting simply on the jagged wood. He watched the two men walk across the distance toward him, his dark hands loose around his knees. At their approach he doffed his hat, not without some ceremony.

The soldier sees him, at a distance, vanish into the desert with the prisoners: “They walked west, unhurried, hand-in-hand like children.” Now a fully-realized archetypal villain, Fierro simply steps out of the frame of the novel, into the murk.

In Part III, the Villa of yore emerges, as if called forth by our collective pop culture imagination. Now in his thirties, he wears military attire, jackboots, a dusty sombrero, two bandoliers, and sits behind a desk in a big chair, smoking cigars, deciding the fate of each citizen dragged before him. Armed men guard his door. The mandate of the revolution is the redistribution of land to peasants, and the removal of the greedy dons, the “great families,” and President Díaz. To some extent, Villa seems to be a simple appendage of the revolution, taking from the dons and giving to the poor, crossing Chihuahua in search of new patriotic recruits: “We spoke to them,” he says, “of pay and food, of rifles and horses. We spoke to them of killing rurales, marauders and roadmen. We spoke to them of uprooting the dons from the valleys where they grew fat on the labor of honest men like themselves. We told them that each soldier would get what was fair to him and at this they rejoiced.”

Nevertheless, Villa remains elusive, complex. We wonder, after watching him murder Refugio, if he cares about anything, or if he is just a psychopath. What does he really think of the revolution? Told he will advance to the rank of captain in the revolutionary army, Villa concedes, “These were strange moments for me, for they sounded at once upon the bottom of things. I admit freely that in these early days of the fight I feigned a conviction that only came upon me at intervals, and never quite the whole.” We now strongly suspect that Villa’s war with Díaz, the grand revolution, has simply been a continuation of Villa’s accumulation of power, a natural progression from his days as a bandito. Although he seems to speak in the voice of the land itself, we do not quite trust him. Or perhaps it is the land itself—which speaks the truth, always, but whose sense of justice is frighteningly barbarous—we do not want to trust:

I say that the revolution is not a series of events. I say that battles are not fought in return for battles which have been fought before. In the time of the revolution the betrayals are perpetual and the injustices flatten out into a mural of humiliation forever in need of bloody correction and all the facts have been lost.

Toward the end of The Beginning of His Excellent and Eventful Career, MacKenzie allows the story to divide into fractured legends, splintered accounts of the infamous “Pancho” Villa. The first person narration slips. MacKenzie does not correct the accounts, or privilege one history over another. He refuses to help us decide whether Villa is, finally, a murderer, patriot, nihilist, or lover. Villa—palpably bewildered by the action around him—sometimes steps out of the frame to speak to us directly, soliloquizing, like Iago:

This is what I know of it. As you can see, it is a story. A story perhaps with even some truth, because that truth is one that speaks to the nature of its protagonist who is such only in the service of another, that other being myself. I am here a name alone, and one that stretches across this country . . .

MacKenzie provides us with an X-ray of human nature: Perhaps it’s meant to be a caveat against autocratic, charismatic leaders whose lust for power goes unchecked—perhaps he is telling us that it’s futile to struggle against the violent forces of nature. Like all art worth its salt, MacKenzie’s novel offers no definitive conclusions. I can only recommend that you visit his weirdly haunting visionary nightmare landscape yourself, and that you go unarmed.