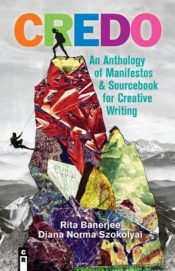

Edited by Rita Banerjee

Edited by Rita Banerjee

and Diana Norma Szokolyai

C & R Press ($20)

by Greg Bem

The relationship between the writer and their practice is ongoing, and this collection feels like a generous gift to those who already write, those who may be dabbling, and those who may be completely stuck in either newness or crisis. In CREDO, this relationship the individual has with their act is explored via three different forms of writing-on-writing: manifestos, statements on craft, and writing exercises. Each section in the anthology contains contributions from different writers, fifty in all, who are connected to one another via the Cambridge Writers’ Workshop, an ongoing project which serves to “create a global network of creative writers, artists, and intellectuals who actively bridge their private aesthetic philosophies with their public forms of art.” The spread is, to some degree, diverse; the writers come from different styles and backgrounds and identities, and we see intricate and personal relationships between the writers and their works through the book’s three sections.

The first section, of manifestos, is as one might expect: a series of grandiose statements on the spiritual underpinnings of how the writer becomes the writer and what the role of the writer (and of the writing) becomes over time. These works are perhaps the most eclectic. Thade Correa’s “Manifesto: Aphorisms on Poetry” opens: “The world is a continually-unfolding dream made of desire, never complete, never to be completed. Endless voyage. The world is poetry.” Later, Laura Steadham Smith describes “Where Stories Come From” in an effective stream-of-consciousness ramble: “I write because I might be the worst person I know. I write because azaleas bloom in spring. I write to remember what it felt like to run through the woods as a kid. I write to become someone else.”

“What is a ‘trans poem?’” asks Stephanie Burt in arguably the most intensely present piece of the entire anthology. Her work “The Body of the Poem” directly speaks to the trans experience and explores the process of gender that sprouts out of these otherwise repetitious conversations on the act of expression. Other noteworthy manifesto contributors include a powerful meditation on skin color and blackness, “You’ll Never Be an Artist!” by Nell Irvin Painter, as well as a memoir on curricula, “Collage and Appropriation,” by the obsessive and scholarly David Shields.

CREDO’s second collection of writings concerns craft. While most of the works on craft concern prose and storytelling, the lessons learnable here could apply to any genre or form in the literary universe. Most important are the snippets of wisdom that fill spaces between relatively endless and rigid anecdotes on what writers should or should not do. “Poems are made out of words, and these words need to be your own,” writes Jaswinder Bolina in “What I Tell Them,” a Zen-like impression straight out of the darkest recesses of the writer’s workshop. In the following “Holding a Paper Clip in the Dark,” Matthew Zapruder writes: “I really like the simultaneous centripetal and centrifugal feelings of these words that want to go in different directions, but also somehow always seem to, in the end, belong together.”

Often the craft statements blend together with the manifestos, especially in tone and approach to writing, but editors Rita Banerjee and Diana Norma Szokolyai should be commended for their efforts to categorize. Other strong writers whose sprawling voices move in so many directions have found a situated place in CREDO—writers like Lisa Marie Basile, Maya Sonenberg, Ellaraine Lockie, Kara Provost, Allyson Whipple, and Nicole Walker—each with a strong voice, and so much to offer.

The final section of the anthology is its most practical; “Exercises” is filled with page after page of idea-generating explorations leading back to the book’s subtitle. If none of the other works served to inspire, certainly the “sourcebook for creative writing” section of CREDO has higher potential. Some exercises are clever and fun, such as Anca L. Szilágyi’s “Summer-Inspired Writing Prompts,” while others like Rita Banerjee’s examination “Rasa: Emotion and Suspense in Theatre, Poetry, and (Non)Fiction” are rooted in the fantastic qualities of language, cultural tradition, and history.

While the book is, as one would expect, creative at its core, this final section is also very rigid both in its contents and the overall tone. Where a flexible, guiltless approach to writing is just as acceptable as the “sit down and write at the same time every morning” mode, it does not make much of an appearance here. Some contributors do emphasize sleep, meditation, breaks, and the possibility of not finding success until one’s midlife, but the book overall maintains a very Western sense of productivity.

Also disappointing is the lack of conceptual and experimental nods and influences (though the Oulipo does make an appearance, as does the occasional Eastern sourcing a la yoga and meditation). Many of the writers appear to be coming out of a uniform MFA/collegiate Creative Writing space, one that carries an air of privilege. Ultimately this leaves the book feeling incomplete and without a full representation of a larger space of serious personal, semi-professional, and professional writers that exist throughout the world today. Still, anthologies like CREDO are helpful collections of reflection and critical insight that often don’t make it beyond the classroom or workshop space.

Despite the shortcomings of the anthology, it can offer much to the general reader. The echo chamber effects of those who appreciate writing may push their own methods and approaches to writing in surprising new directions—or, alternatively but as supplement, inspire greater and more complex degrees of reflection and understanding of how to examine writing as a passionate, invigorated, and intentional practice.