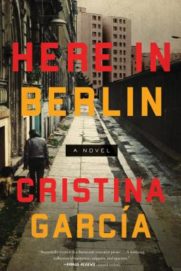

photo by Isabelle Selby

Interviewed by Allan Vorda

Cristina García was born in Havana in 1959, and although her family fled Cuba for New York City in 1961 (shortly after Fidel Castro came to power), her home country has made an indelible mark on her fiction. Prior to becoming an acclaimed writer, however, García received a B.S. in political science from Barnard College and a master’s degree in international relations from Johns Hopkins University. For almost ten years she worked primarily as a journalist for several publications before deciding to devote herself to fiction in 1990. Her first novel, Dreaming in Cuban, was published in 1992 and was nominated for the National Book Award; her seven novels since include The Aguero Sisters, which won the Janet Heideger Kafka Prize, and King of Cuba, which is being adapted into a play as we speak.

García’s seventh novel, Here in Berlin (Counterpoint Press, $26), was released in 2017. The story revolves around an unnamed Cuban narrator known simply as “The Visitor” who travels to the German capital in 2013; she then recounts thirty-five varying tales of Berliners she meets, many of whom recall personal episodes of World War II and its aftermath. It is a fascinating addition to García’s body of work, one that expands upon her recurring themes of politics, cultural memory, and how identity can be constructed from multiple viewpoints.

García’s seventh novel, Here in Berlin (Counterpoint Press, $26), was released in 2017. The story revolves around an unnamed Cuban narrator known simply as “The Visitor” who travels to the German capital in 2013; she then recounts thirty-five varying tales of Berliners she meets, many of whom recall personal episodes of World War II and its aftermath. It is a fascinating addition to García’s body of work, one that expands upon her recurring themes of politics, cultural memory, and how identity can be constructed from multiple viewpoints.

Allan Vorda: Here in Berlin is narrated by the Visitor, a Cuban-American middle-aged woman who has been divorced and has a daughter living in Barcelona. What was the inspiration for the Visitor (who is perhaps not unlike yourself), as well as the concept of relating thirty-five vignettes in which Berliners discuss their past?

Cristina García: The Visitor was the hardest character for me to write. At first, I used her as a kind of scaffolding to elicit stories from the characters and fully expected to cut her out once the stories were harvested. Eventually, I realized that her presence was essential. Listeners are as crucial to storytelling as storytelling itself.

AV: “On her twelfth day in Berlin, a young father asked the Visitor for directions in German, to which she correctly replied. . . . Thus, her mission began.” Are the stories you tell based on people you met or read about, or are they purely fictional characters? If they are based on actual people, then how did this come about?

CG: The characters are fictional but emerged out of a great deal of historical research, eavesdropping, casual conversations with Berliners, and, of course, my hyperactive imagination—such as the story about the Cuban boy who was kidnapped by the crew of German submarine during World War II. But I wanted the format to blur the distinction between fiction and fact.

AV: In one of the early “The Visitor” chapters you state: “Berlin was altering the Visitor, carving out space for silence, hallucinations, distortions.” Then in a later chapter you write: “People asked her: ‘Why are you here? What do you want?’ Her reasons had changed. Now it was war that kept her here; also Eros and pathos, the impossibility of looking away. A different mission.” Did your perspective change in any way the longer you stayed in Berlin? Also, did you feel that because you are an outsider, your writing might be criticized for bringing up a past that Germans want to but cannot forget?

CG: Yes, I went to Berlin, much like The Visitor, in search of stories about Cuba’s relationship with the old Soviet bloc. But the city itself seduced me, provoked me, coaxed me into telling stories other than what I had planned. The city whispered in my ear continually for the three months I was lucky enough to live there. Also, I felt that my outsider status gave me the freedom to probe where others might not.

AV: You have so many memorable characters in this book, such as Ernesto Cuadra (a Cuban who is kidnapped onto a German U-boat), Sophie Echt (a German-Jew whose husband helps her hide in a sarcophagus), and Christine Meckel (a nurse who kills her patients). Out of the thirty-five stories, is there a particular character you like the most?

CG: I think I’m most fond of the characters in the opening and closing stories of the book: Helmut Bauer, who was a young boy during World War II and gives us the wonder and horror of that perspective; and Lukas Böhm, who grows up to be a classical clarinetist. Both boys lost their fathers—a zookeeper, and a musician, respectively—during the war and carried those scars, with a poignant dignity, their entire lives.

AV: You use a quotation by Klaus Filbinger, a former Nazi judge, to open the chapter titled “Hunters”: “What was right yesterday, can’t be wrong today.” This is a fascinating sentence, since several of your characters try to justify their actions for Nazi Germany during World War II. How did you deal with coming up against such examples of what Hannah Arendt called “the banality of evil”?

CG: History of all kinds—official, revisionist, national, familial, personal—endlessly fascinate me. To create narrative, to choose one version of events over another, tells us everything about the storytellers themselves. Every narrative has an emotional urgency that conforms to what the storytellers need to convey for their own reasons, conscious or not.

AV: There are numerous references to the atrocities committed by the Russians when they entered Berlin at the end of World War II. Were these stories ones that still linger in the minds of the Germans who still remember those days? What are your thoughts about the Russians and international diplomacy today?

CG: There were no shortages of atrocities on both the Russian and German sides of the war. Yes, I believe the horrors that were perpetrated live on not only in the survivors themselves but in those who come after them. There is a whole new branch of brain research focused on the intergenerational inheritance of trauma. In my opinion, the best chronicler of Russia today is the fearless journalist Masha Gessen. The Road to Unfreedom, the most recent book by Yale historian Timothy Snyder, is a brilliant, penetrating look at contemporary Russia. I defer to them.

AV: While you do not mention Gunter Grass’s allegorical novel about Nazi Germany, The Tin Drum, you do allude to its two main characters, Oskar and Roswitha. What made you bring up Grass’s novel in this subtle fashion?

CG: I remember reading The Tin Drum in college and the huge impact it had on me as both a work of extraordinary literary merit as well as historical testimony. The novel took me deeper and further into the damaged psyches of war than any history book ever could. I couldn’t have known it then but Grass ultimately opened up this possibility as an ideal for my own work.

AV: Rudolf Hess was convicted of Nazi war crimes and was incarcerated at Spandau Prison from 1947 to 1987. He lived out his life as the sole prisoner in the entire prison until he committed suicide at age ninety-three. The utter loneliness he had to have experienced is incomprehensible. Was there any consideration about using Hess in your novel?

CG: His story is an astonishing one and I was riveted by it. But Hess’s story is also one of World War II’s most well-known ones. I was more interested in exploring the hidden interstices of the war—particularly in Berlin, the epicenter of the Third Reich. The stories that rarely, if ever, get told.

AV: Several of your characters have problems with their vision, such as needing cataract surgery. Lukas Böhm is one such figure, who states at the end of the novel: “My eyes are clouded, my hands no longer steady. And I wait for death, without Father’s courage, to end it on my own terms. Dear Visitor, upward of two hundred sparrows a year die against my windows, blinded by what they can’t see.” Essentially, many of the old Berliners have a distorted vision of their past. Did you find this to be true even in the 21st century during your time in Germany?

CG: I’m married to an ophthalmologist so I have more than a passing acquaintance with eye disease. More importantly, I thought it an apt metaphor for examining the distortions of memory. What, how, and why we remember what we do is inextricably connected to what we allow ourselves to see.

AV: In 2015, Angela Merkel’s stated that Germany would accept hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees. Do you think Merkel’s decision is based on a sense of guilt about Germany’s haunted Nazi past, which is also a theme in your book?

CG: As unpopular as her resolve was with her own citizens, I believe Merkel’s decision was an ethical, humane, and generous one, no doubt informed by Germany’s Nazi past.

AV: Do you foresee a backlash by conservative German groups against the Syrian immigrants, especially in light of such books as Douglas Murray’s The Strange Death of Europe?

CG: I’m not an expert on the refugee crisis in Germany. However, history tells us that the newest immigrants anywhere—especially in times of political and economic upheaval—often become scapegoats. We need look no further than our own shores for evidence of this.

AV: I’ve heard that a play based on your 2013 novel King of Cuba is coming out this summer. Can you discuss how this came about?

CG: Yes, I adapted King of Cuba as a two-act dark comedy and it premieres this summer at Central Works Theater in Berkeley on July 21. I’m thrilled! After twenty-five years of writing novels, I wanted to try my hand at another genre—and this is the result. I’m loving the collaborative nature of it, too.

Here’s a link: http://centralworks.org/king-of-cuba/ .

AV: The epilogue you use to close the novel is wonderful: “And now? What did she want? Quiet, resplendent days in the light. Her daughter a breath away. And a butterfly net with which to swipe the air, trapping bits of flying color here and there. Yes, she might spend the rest of her life doing nothing more than that.” I hope you are not implying that your writing days are over.

CG: Not at all! I don’t think writers ever retire, do they?!