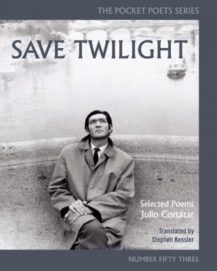

Julio Cortázar

Julio Cortázar

translated by Stephen Kessler

City Lights Books ($17)

by John M. Bennett

Julio Cortázar (1914-1984), the great Argentine novelist whose highly innovative and experimental fictions have had a lasting and influential impact on literature world-wide, was also an excellent and innovative poet, and his work in that genre deserves to be better known. Fortunately, the author of Rayuela (Hopscotch) is well represented as a poet in a new and greatly expanded edition of Save Twilight, Number 53 in City Lights' Pocket Poets series. Originally published in 1997, this new, plump little volume (which would only fit in the largest pocket of your cargo pants) is an excellent introduction to the author's poetry, which is as fascinating and compelling as anything he wrote.

Cortázar's poetry varies in style and tone. His most frequent voice is a personal one in which he is not writing “poetry” but rather talking to himself or to a listener. This is a style found also in some of Roberto Bolaño's poetry; Bolaño was from a younger generation, but both writers are best known as novelists, and both professed poetry as their first love. What is striking about both poets' language is the emotional intensity they achieve while using an extremely conversational diction. This is a very difficult effect to create, and can only be done when the poet is speaking of things he or she feels very strongly and immediately. Some of the poems are set up as “prose,” and use the same sort of diction.

But this is not the only voice in Cortázar's repertoire. There is also a kind of surrealism in the vein of early Pablo Neruda, although it has a stronger socio-political aim (“where shrieking rats on their hind legs / fight over scraps of flags”), and there are a number of more formal poems—a series of sonnets, for example, reminiscent of the sonnets of Mallarmé. The poems in this somewhat Parnassian mode are so mysterious, so ensconced in their language, that they resist being translated, except perhaps in a strictly literal way, but there are others, too, often written in rhyming quatrains, that are truly excellent poems, though probably not to the tastes of many current English-language readers of poetry. Save Twilight focuses on the more conversational and explicitly personal poems, such as “Profit and Loss,” which suggests that Cortázar's interest in world affairs, in contrast to intense and intimate issues, is something tranquilizing and calming:

Sometimes you return in the evening, when I'm reading

things that put me to sleep: the news,

the dollar and the pound, United Nations

debates. It feels like

your hand stroking my hair.

What is poetry for Julio Cortázar? In a number of places, he addresses this question. In an untitled prose text in this book (indexed as “A friend tells me . . .”) he deplores “that seriousness that tries to place poetry on a privileged pedestal, which is why most contemporary readers can't get far enough away from poetry in verse.” He continues by saying “Putting this book together . . . continues to be for me that chance operation which moves my hand like the hazelwood wand of the water witch; or more precisely, my hands, because I write on a typewriter the same way he holds out his little stick.” In another prose poem, “Most of what follows. . . ,” he quotes Dr. Johnson from Boswell's Diary: “‘Read over your compositions, and wherever you meet with a passage which you think is particularly fine, strike it out.’”

Cortázar was a poet who can be seen as taking a big step beyond the styles of Latin American Modernismo, which was itself a reaction against late romanticism and is considered by many to be the first uniquely Latin American style in poetry. Cortázar's roots are in Modernismo, however, and some of the sense of loss and exile that runs through his work can be traced to leaving behind the elegant poetic modes of the early twentieth century. A poem not included in this selection, “Éventail pour Stéphane,” is a poem in a rather Modernista style and form addressed to Mallarmé, one of the poets admired by the Modernistas because he conjoined Symbolism and Parnassian aesthetics in his work. Using the principal symbol of Modernista aesthetics, the swan, it is a poem which suggests that poetry formed the foundation of Cortázar's literary activities:

Pues sin cesar me persigue

la destrucción de los cisnes.But ceaselessly I am pursued

by the destruction of the swans.

(my translation)

I have already mentioned Roberto Bolaño, but it might be useful to compare Cortázar's poetry to that of other major Latin American poets. The Chilean Nicanor Parra, Cortázar's contemporary and the creator of “Anti-poetry,” brings up the question of how much the Argentine can be considered an anti-poet. In the sense that his poetry takes several steps beyond the poetics of Modernismo, he can be called that. The same would hold true for Pablo Neruda, and for the at times desperate and expressionistic surrealism of Vicente Huidobro, who preceded Cortázar by a generation. Or Huidobro's contemporary, César Vallejo, whose early poems contain traces of Modernismo which evolved into some of the most intense Futuristic poetry ever written, much of it constructed on a base of conversational language. The Nobel-winner Octavio Paz's highly literary and elegant poetry is quite different from Cortázar's but also has its roots in that early twentieth-century revolution in poetry. All of these poets reacted against Modernismo in unique ways, and each subsumed Modernismo in their work; it is the matrix from which they grew.

Stephen Kessler's expanded edition of Save Twilight is a real gift; his translations are eminently readable and repay repeated readings: the poems will seem different each time. Cortázar is a poet of many styles and voices, and this selection has spurred me to revisit his poetry, and re-read some of his great novels, an experience that is greatly enriching. What more could one ask of poetry, pocket or otherwise?