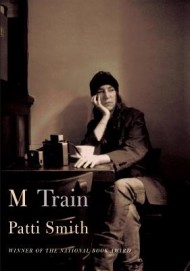

Patti Smith

Patti Smith

Knopf ($25)

by Christopher Luna

M Train, Patti Smith’s follow-up to the National Book Award-winning Just Kids, is an elegiac exploration of loss, the mystical power of objects that hold sentimental value, the joy to be taken from a good detective story, and the inexorable pull of place. Our narrator travels in an eternal search for good coffee, following clues left behind in the work of cultural elders such as Arthur Rimbaud, Frida Kahlo, Jean Genet, and Paul Bowles. This leads her on a journey that serves as a kind of divination born of the fan’s devotion and the artist’s hunger for answers. While hers is no traditional memoir, we are treated to poetic ruminations on the nature of time and deep knowledge on arcane subject matter such as the exact worth of a hill of beans. At a book launch event at Portland’s Newmark Theater in November, Smith explained that her previous memoir was written because it was her friend Robert Mapplethorpe’s dying wish that she tell their story. Therefore, Just Kids had a design, and she felt a sense of responsibility to New York City, the culture, Mapplethorpe, and the other people in the book. She enjoyed being free of that burden as she worked on the new book, one that she “never planned to write, recording time backwards and forwards.”

When Smith arrived in New York City from New Jersey in 1965 “just to roam around . . . nothing seemed more romantic than just to sit and write poetry in a Greenwich Village café.” She eventually found Caffe Dante, near Bleecker Street, and later, Café ‘Ino on Bedford Street, a daily stop that inspires many of the ruminations in the memoir. Fans will love acquiring a sense of her daily routine and the insight into her thought process. However, those seeking the straightforward trajectory of linear narrative won’t find it here. Smith’s recollections wander back and forth between past and present, and her stories can leap suddenly from one continent to another without warning. How tolerant one is of her many digressions may be a reflection of one’s love for her work; the writing is exquisitely vulnerable and inquisitive, but the story does not follow anything resembling a narrative arc. It is best just to go with it, keeping in mind that our own memories can be similarly disjointed and incomplete.

Smith loves cafes so much that she was preparing to open one when she met Fred “Sonic” Smith, the fellow musician who became her husband and the father of her two children. Soon after they fell in love, the couple moved to Detroit. Despite the lack of coffee shops, Smith describes these years living “in an old stone country house on a canal that emptied into the Saint Clair River” in Michigan as “mystical times. An era of small pleasures.” One inspiring aspect of Smith’s approach to life is her willingness to accept the unexpected detours. Before their children were born, she and Fred traveled, made plans to buy a lighthouse, and he attempted to obtain a pilot’s license. Although they did not complete all the projects they discussed, Smith is quite philosophical about it all:

Not all dreams need to be realized. That was what Fred used to say. We accomplished things that no one would ever know. . . . For a time we considered buying an abandoned lighthouse or a shrimp trawler. But when I found I was pregnant we headed back home to Detroit, trading one set of dreams for another.

Fred finally achieved his pilot’s license but couldn’t afford to fly a plane. I wrote incessantly but published nothing. Through it all we held fast to the concept of the clock with no hands. . . . Looking back, long after his death, our way of living seems a miracle, one that could only be achieved by the silent synchronization of the jewels and gears of a common mind.

Like Just Kids, which contained many stories of time the author spent with artists such as Harry Smith and Sam Shepard, M Train also features many memorable encounters. Smith comments that her opportunity to meet chess champion Bobby Fischer while visiting Iceland was proof “that without a doubt we sometimes eclipse our own dreams with reality.” Fischer asked Smith to sing Buddy Holly for him, and then the two of them sang popular songs together as Fischer’s bodyguards stood nearby.

We are also allowed to sit in on her conversations with writers such as William S. Burroughs and Paul Bowles, and tag along on several trips to the homes and gravesites of thinkers and artists including Bertolt Brecht, Akira Kurosawa, and Sylvia Plath. While many of these stories are brief, they are densely packed with Smith’s insight, wit, and imagination, as in the moment when a chance meeting with actor Robbie Coltrane in London is followed by a brief conversation with the floral bedspread in her hotel room.

Her last visit with Burroughs included a viewing of “a print of William Blake’s miniature of The Ghost of a Flea,” which depicts “a reptilian being with a curved yet powerful spine enhanced with scales of gold.” When Burroughs told her that he identifies with the creature, she failed to ask him to elaborate. Her curiosity lead to the following inspiring passage:

William the exterminator, drawn to a singular insect whose consciousness is so highly concentrated that it conquers his own.

The flea draws blood, depositing it as well. But this is no ordinary blood. What the pathologist calls blood is also a substance of release. A pathologist examines it in a scientific way, but what of the writer, the visualization detective, who sees not only blood but the spattering of words? Oh, the activity in that blood, and the observations lost to God. But what would God do with them? Would they be filed away in some hallowed library? Volumes illustrated with obscure shots taken with a dusty box camera. A revolving system of stills indistinct yet familiar projecting in all directions: a fading drummer boy in white costume, sepia stations, starched shirts, bits of whimsy, rolls of faded scarlet, close-ups of doughboys laid out on the damp earth curling like phosphorescent leaves around the stem of a Chinese pipe.

Another theme of the book is the love of literature. While Smith confesses that there have been times when she has read entire books and been unable to retain anything, what she is able to recall is quite remarkable. We learn of her lifelong obsession with books and the impact that writers such as Haruki Murakami and W.G. Sebald have had on her life and her own work. Writers will be able to relate to a passage in which she makes use of lists, which she compares to “small anchors in the swirl of transmitted waves, reverie, and saxophone solos.”

Along with her obsession with books and coffee, Smith also ascribes spiritual qualities to objects that once belonged to her idols, such as Herman Hesse’s typewriter and Virginia Woolf’s walking stick. Her love of books often led to quests, such as the journey she took to Casa Azul in Mexico in 1971 after reading The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera. Not only had the book gifted to her by her mother when she turned sixteen captured her imagination, but “William Burroughs had told me the best coffee in the world was grown in the mountains surrounding Veracruz.” While in Casa Azul, Smith visited “the house where Trotsky was murdered,” and not only gained permission to photograph Frida Kahlo’s dresses, but was even invited to “rest in Diego’s bedroom” when she began to feel lightheaded.

An air of nostalgia and mystery pervades the memoir, as when Smith longs for the days when it was tokens rather than MetroCards that one used to gain admission to the New York City subway. She also delves into the emotions evoked by lost possessions. She wonders, “Do our lost possessions mourn us?” She laments the loss of a raggedy black coat, a moth-ridden birthday gift from a poet who had given the garment she had “secretly coveted” to her right off his back. Wearing the coat she “felt like myself.” Misplacing it leads her to this poignant realization: “Lost things. They claw through the membranes, attempting to summon our attention through an indecipherable mayday. Words tumble in endless disorder. The dead speak. We have forgotten how to listen. Have you seen my coat? It is black and absent of detail, with frayed sleeves and a tattered hem. Have you seen my coat? It is the dead speak coat.”

The book includes 55 haunting photos by the author, such as an image of the “oval table where Goethe and Schiller once spent hours conversing,” an “innately powerful” object which Smith sees as “a valuable element for comprehending the concept of portal-hopping.” Just as she eventually returned to New York to pick up right where she had left off as a cultural shaman and a punk rock force of nature, she also revisited her dream of opening a coffee shop. Some of the most powerful writing in the book appears in her description of New York during and after Hurricane Sandy, a natural disaster that temporarily prevented her from having access to the small bungalow she purchased on Rockaway Beach in the hopes of fulfilling her youthful dram of opening a café. The chaos and destruction caused by Sandy reminded Smith of her husband’s death, which had occurred many years prior during a “raging thunderstorm” in Detroit: “Fred, fighting for his life, could be felt in the howling wind. A great branch from our oak tree fell across the driveway, a message from him, my quiet man.” Fred died alone in a hospital while her family worked together to get through the storm.

Loss is an inescapable part of life, and one of the major themes that runs through M Train. Smith has endured her share; just one month after losing her husband, her brother died suddenly of a “massive stroke.” Who among us cannot relate to her wish to have it all back: “We want things we cannot have. We seek to reclaim a certain moment, sound, sensation. I want to hear my mother’s voice. I want to see my children as children. Hands small, feet swift. Everything changes. Boy grown, father dead, daughter taller than me, weeping from a bad dream. Please stay forever, I say to the things I know. Don’t go. Don’t grow.” M Train is a raw, witty, melancholy reverie, a collection of memories and wishes that speaks directly to our collective humanity. We are fortunate to have Patti Smith to lead us on this investigation of love, loss, compassion, and wide-eyed wonder.