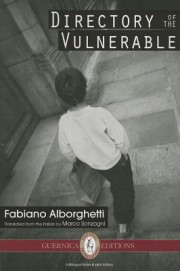

Fabiano Alborghetti

Fabiano Alborghetti

Translated by Marco Sonzogni

Guernica Editions ($20)

by Graziano Krätli

Current events and crime news keep feeding fiction and creative nonfiction alike, but remain difficult to digest in poetry. This is not because of any real or presumed affinities between “news style” and other forms of “ordinary writing,” but simply because some “currencies” are easier to circulate and circumvent in prose than in verse. This is why Fabiano Alborghetti’s two fine collections to date, L’opposta riva (The Opposite Shore, 2006 and 2013) and Registro dei fragili. 43 canti (2009; Directory of the Vulnerable) represent almost an anomaly, if not a challenge, in the world of contemporary Italian poetry. The anomaly consists largely in the poet’s adoption of a voice (or voices) other than his own, in the process divesting himself of his poetic persona to invest in the cultural and linguistic expropriations (and reappropriations) that such borrowed voices represent, whether they belong to the tattered margins or the dead center of society. Making such adoptive voices redemptive is a high-risk investment, and it is more so for a poet than for a prose writer.

In L’opposta riva, the voiceless are sixty-three illegal immigrants from the Balkans, North and West Africa, whose names, ages, and origins are listed at the end of the book (unless they appear simply as “unknown,” which makes their voicelessness even more crying). The many forms of displacement, dispossession, and violation they embody were recorded by Alborghetti during the three years he lived at various immigrant camps around Milan (while working, of all places, at a luxury hotel). Immigration, its causes, hopes, and consequences, have been explored before, in poetry and prose, by a number of contemporary Italian writers, notably Eraldo Affinati and Erri De Luca. What makes Alborghetti’s book unique is the way in which its borrowed voices (and their own second-language idiosyncrasies) shape a distinct poetic idiom, creating an elevated style in which classical resonances and literary erudition are shined through the prism of broken linguistic and human material.

A somewhat similar kind of ethnographic field work informs Directory of the Vulnerable, Alborghetti’s next collection and his first to appear in English. (The publisher is planning to bring out a translation of L’opposta riva sometime between the end of 2016 and mid-2017). Prompted by a murder case occurred in 2006, the poet turned his attention from the Other—the dispossessed, displaced, undocumented alien—to his own fellow citizens, the affluent and alienated suburban middle class to whom aliens (legal or illegal) are but another docu-soap they watch on television. Instead of visiting immigrant camps, talking to their residents, and listening to their stories and pleas, Alborghetti took a stealthier approach, infiltrating “different family groups, noting their behaviours, the dialogues, the different relations that govern the physical, oral and moral behaviour of a family.” He followed them “in the shopping centres, the boutiques, the restaurants . . . spied on them among the stalls of a market or [from] behind the hedges of private gardens, listening and taking notes.” These field notes allowed him to insinuate himself imaginatively in the private lives and minds of his two protagonists, and to ventriloquize their growing estrangement from each other.

The facts are faceless enough that they could have happened in any industrial society. A woman trapped in a dead-end marriage kills her young and only son, whose birth had ended her dream of becoming a fashion model. The murder is never mentioned in the book, or only indirectly through the smoke screen of media interviews, expert debates, and the comments “of those who are right because they were there.” What interests Alborghetti is neither the reality of the facts nor the probability of their causes, but the complex universe represented by the inner and outer lives of his protagonists, the husband and wife whose ambitions, expectations, frustrations, and obsessions are typical of a late capitalist society driven by hyper-consumerism, self-gratification, and celebrity worship. In sum, all the rich, contradictory, and hard-to-define dark matter that feeds a writer’s imagination but is normally off limits to the journalist and the scientist.

The book is divided in three parts and forty-three cantos, each one consisting of a variable number of unrhymed tercets and ending with a single line. The first thirty-seven cantos (“Pictures at an Exhibition”) trace the downward path of the couple through various stages of separation, each picture duly framed by a specific location or situation: the restaurant, the gym, the backyard barbecue, the beach, the dining room, the living room, and of course the bedroom, both marital and extramarital. The second and third sections consist of three cantos each and deal with the aftermath of the tragedy, the sordid and short-lived media attention (“Judicial Theses”), and the return of the quiet after the dust is settled (“Directory of the Vulnerable”). The progression is contrapuntal, the rhythm unrelenting, the pace fast and feverish. The dynamic potential of the three-line construction is enhanced by the frequent use of repetition, assonance and alliteration.

The resulting lines, in Italian, convey most effectively the peculiar attitudes of the protagonists, often with the fastidious pointedness of a tongue-twister (“Poi la spesa si contava controllando lo scontrino” and, a few lines later, “Lo scontrino controllava fermo fisso a lato cassa.” They also represent a translator’s nightmare, as no amount of lexical or semantic competence will produce a satisfactory equivalent, either in English or any other language. The best a translator can hope and strive for, instead, is a satisfactory compromise—a version that is competent and compelling at the same time, combining a thorough understanding of the original and a sharp rendition of it in the target language. Unfortunately, this is achieved only partially and sporadically by the version under review. Translator Marco Sonzogni, although clearly aware of the challenge presented by the original and its “almost hypnotic rhythm,” tends to follow it too closely and trustfully, thus giving us lines that rarely retain the mordant conciseness and the vibrant energy of the original, but that are consistently longer and heavier, often sluggish and occasionally dull. This is also due to the awkward choice of certain words and expressions, which depart from the original for no apparent reason. Consider, for example, the first of the two lines quoted above, which is rendered

Next the bill for the shopping gets checked,

checked that nothing’s being charged in error;

the check-out operator is up to it, ringing up items you haven’t bought

While possibly justified by the fact that the translator is based in New Zealand, the use of “bill” instead of “receipt” for the Italian scontrino, and of “check-out operator” instead of “cashier” for cassiera, does not help retain the rhythm of the original; on the contrary, the repetition of “checked,” “checked” and “check-out” sounds rather toneless if compared to “si contava controllando lo scontrino.” Similar examples may be found in virtually any canto of the book.

It was Pound who said that “a translation must be more concise than the original,” and who tried to live up to his pronouncement with his versions of classical Chinese, Anglo-Saxon, Provençal, and medieval Italian poetry. In reality, the practice of turning a text, especially a poetic text, from one language into another tends to add rather than subtract, regardless of what the source and target languages are; and what is added is often redundant and occasionally irrelevant, if not detrimental to the overall understanding of the text. This is to a great extent inevitable and frequently attributed to the lure of the original, its power to mesmerize and captivate (in the original sense of “take captive”) with its lexical and syntactic peculiarities, its rhythmic aspects, its layers of meaning. Each text is a labyrinth and a riddle, and the spell it casts upon the reader is considerably more dangerous if he or she doubles as translator. In order to resist the power of seduction of the text and break its spell, such a translator must take control of its authority and—hard as it sounds—practice systematic, or at least selective authoricide. (Isn’t the translator’s an Oedipal condition anyway?) Facing this dilemma, Alborghetti’s translator took a more accommodating approach, producing a version that is deferential rather than distinctive, and often prosaic without being necessarily faithful, as an attentive bilingual reader will be able to see.