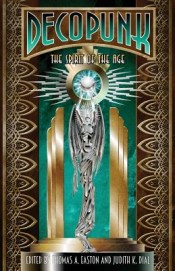

Edited by Thomas A. Easton

Edited by Thomas A. Easton

and Judith K. Dial

Pink Narcissus ($15)

by Kelsey Irving Beson

In their feisty introduction to the short story collection Deco Punk: The Spirit of the Age, editors Thomas A. Easton and Judith K. Dial outline their vision for a new literary movement of science-driven fiction chronologically situated between the two World Wars. While the editors cite steampunk as an influence, they ultimately frame deco punk as opposed to the popular genre, which is “past its prime . . . static and antiprogressive.” They assert that deco punk, with its focus on technological rather than fantastic elements, is “more in tune with the 21st century.” To support this claim, they cite steampunk’s improbable and ahistorical conventions, both the funny (such as top hats worn while piloting dirigibles) and the not-so-funny (such as the glossing over of the Victorian era’s oppressive gender roles and marginalization of the poor). As the first story in the collection serendipitously states, “The age of steam is done, however strong it now appears.”

In addition to steampunk, the writing displays the influence of a multitude of other genres, to varying effect. At its strongest, this pastiche feels loving and organic—Golden Age comics characters fit seamlessly into a plot straight out of Edgar Rice Burroughs in Paul Di Filippo’s “Airboy and Vooda Visit the Jungles of the Moon”; William Racicot’s improbably endearing “Berenice Bobs Your Hair” reimagines F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age would-be social climber as a witchy hairdresser. Inevitably, some of the stories are less nimble as they hop across narrative tropes. For example, the initially promising “Quicksilver” goes from Thieves Like Us to The Boys From Brazil fast enough to give the reader whiplash. Similarly, the collection’s first entry, “Silver Passing in Sunlight,” wants to be both an Exorcist-tinged possession tale and a tech-driven, historically-grounded narrative, but the supernatural element feels tacked-on and, ultimately, the most compelling character is a train. While it’s an intriguing conceit, unfortunately, the end result isn’t exactly two great tastes that taste great together. However, even when things don’t quite turn out, Deco Punk’s willingness to explore different tropes and tones works in the book’s favor—each story stands out from the others, no mean feat in genre fiction.

Similarly, several of the stories have both paranormal and scientific overtones, with the former occasionally outweighing the latter. Readers interested in the more fantastic or character-centric elements of genre fiction will find things to like here, in spite of the fact that the collection’s theme is nominally technology-driven. In others, progress and discovery are the true heroes, in all their shiny, Gernsbackesque glory. Optimism isn’t the only thing that these works have in common with early science fiction: like the speculative stories of the between-the-wars milieu that inspired them, occasionally the plots can feel like mere contraptions on which to hang the science. Fortunately, these moments are relatively rare, and the best stories manage to integrate science, character, and narrative in a way that is satisfying, even poignant—such as Shariann Lewitt’s “Symmetry,” whose heroine, living in a Weimar Berlin circumscribed by starvation and sexism, finds comfort in math, which “has shown me the clear, safe place where knowledge is true and eternal.” In addition, many readers will appreciate the fact that the collection prominently features women authors and sympathetic, fully-realized female and gender-bending characters.

Deco Punk’s greatest strength lies in its granularity—in terms of genre, narrative strategy, and tone, each of these stories is distinct and memorable. There’s also enough similarity here for the collection to feel satisfying and cohesive, warts and all. While fans of speculative and fantastic fiction can probably find room on their shelves and in their hearts for both deco and steam, Easton and Dial make a strong case for the relevance of their (ostensibly) more down-to-earth brainchild over its fanciful predecessor.