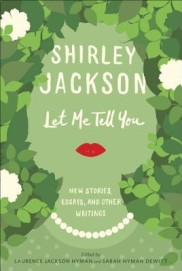

Shirley Jackson

Shirley Jackson

Random House ($30)

by Rob Kirby

Shirley Jackson has always been an anomaly. Her works range from the dark worlds of her timeless short story "The Lottery" and gothic novels like The Haunting of Hill House (1959), to the warm and funny domestic stories she wrote mostly for women’s magazines like Good Housekeeping and Woman's Home Companion (collected in her celebrated 1953 book Life Among the Savages and its 1957 sequel Raising Demons). Writing popular fiction along with the “serious” likely contributed to her fading reputation in the years following her death in 1965 at age forty-eight. But for her fans, her body of work integrates into a distinct, uniquely personal vision, no matter the subject matter or tone. In recent decades Jackson has been increasingly recognized as an important and influential mid-century American writer, including by noted authors such as Neil Gaiman, A.M. Holmes, Jonathan Lethem, Joyce Carol Oates, Paul Theroux, and (most famously) Stephen King.

Let Me Tell You is the third posthumous collection of Jackson’s previously uncollected or unpublished work compiled by her family members. Come Along With Me (1968), edited by her husband, the noted literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman, remains for me the strongest and most unified of the three. Just an Ordinary Day (1997), edited by her eldest son and youngest daughter, Lawrence Jackson Hyman and Sarah Hyman DeWitt, is a bit wobblier, featuring too many stories at which Jackson herself would have probably blanched upon exhuming. This latest, lovingly produced volume sits squarely between the others. As with Ordinary Day there is some work that feels somewhat unfinished or insubstantial, but the curation is clear and the scope expansive; there are some very strong pieces included that deserve their day in the sun.

The book is divided into five sections: the first consists of unpublished and uncollected short fiction; the second is personal essays and reviews; the third features some early, World War II-era short stories; the fourth features a selection of her humorous family stories and anecdotes; and the final section is devoted to lectures about the craft of writing. Throughout there are Jackson’s charming little doodle-y cartoons, and a lovely amateur watercolor graces the endpapers. Writer Ruth Franklin, author of a forthcoming biography of Jackson, provides a smart, concise introduction, titled “I Think I Know Her.”

The two fiction sections and the one devoted to Jackson's writings about writing are the strongest, featuring her work in a variety of styles, genres, and tones. Speaking of The Haunting of Hill House in her lecture "How I Write," Jackson notes that “reality is the key issue” of the novel. This insight underscores the fact that many of Jackson’s stories, such as “It Isn’t the Money I Mind” and “Company for Dinner,” feature characters whose perceptions of reality are off-kilter. In other tales, characters try to alter their realities: the mousy, nondescript collegiate girl in “Family Treasures” engages in petty thievery in an effort to improve her social status, while the rather desperate protagonist of “The Lie” attempts to right a forgotten, past moral infraction in an effort to change her unhappy present situation.

In some of Jackson’s finest tales here and elsewhere, reality is upended by unreality. In the elegantly crafted “Mrs. Spencer and the Oberons,” the unpleasantly rigid, supremely snobbish Mrs. Spencer finds herself helplessly isolated from a happy town celebration—her own family in attendance—in an eerie, perhaps supernatural turn of events; whether the character is subject to the uncanny or simply her irrational prejudices made manifest, it is a fine tale of poetic justice. In the Kafka-esque "Paranoia," an ordinary businessman finds himself pursued at the end of the workday by a malevolent man in a light hat, for unknown reasons. Eventually, it appears that other strangers are in on the pursuit. A master of dark fiction, Jackson stokes an atmosphere of rising dread both in this and the outright mythological world of "The Man in The Woods."

Jackson also pitilessly explores the more unattractive sides of human nature in nuanced stories like “4-F Party” and “The Bridge Game,” in which husbands and wives act out insidious jealousies and hostilities, with others caught in the crossfire. In other tales, such as the title piece and “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” mean girls torment adults for sport. Jackson was acutely aware of the evils people carry within; it was a theme that she returned to again and again.

Other stories are of a type not much seen previously in Jackson’s oeuvre: “Homecoming” is a quiet, contemplative tale of a woman awaiting her husband’s return from war, while “Bulletin” and “Showdown” delve into science fiction territory. While these tales and others display Jackson’s willingness to experiment in a variety of genres and tones, they are best viewed as ephemera, and not as representative of her best work. Similarly, most of the family stories and housewifely musings in section four remain, at best, light reading (Life Among the Savages remains the peak in this mode of her storytelling).

The lectures are illuminating, offering not only a look into her creative process but some genuine food for thought for other writers. “Garlic in Fiction” in particular offers a fascinating glimpse into how Jackson builds a set of “cumulative symbols” to write a tricky transitional passage in The Haunting of Hill House. “This collection of weighted words,” she writes, “can only be used like garlic, where they will do the most good, and they must never be used where they will overwhelm the flavor of another passage.”

Uneven though it may be, Let Me Tell You is a welcome collection, essential for Jackson-philes. More casual or novice readers, however, are advised to start with any number of Jackson’s finest books: The Lottery and Other Stories, Life Among the Savages, The Haunting of Hill House, We Have Always Lived in the Castle, or Come Along with Me. Now that all of Jackson’s previously forgotten or little-seen work has (presumably) been brought to light, perhaps someday a collection featuring only the very best of her short fiction and stories will be curated for posterity. Shirley Jackson’s legacy deserves nothing less.