Henry Lyman

Henry Lyman

Open Field Press ($17)

by Rebecca Hart Olander

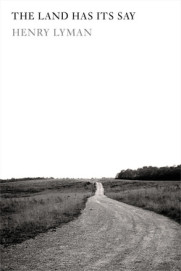

After a lifetime of editing, translating, and championing the poetry of others, Henry Lyman gets his own moment in the sun with The Land Has Its Say. The cover photograph of a dirt road winding through an open landscape is an eloquent visual map of the book’s wondering, wandering nature—the road widens out to meet us and stretches beyond our view, just as Lyman’s poems do.

The Land Has Its Say possesses an elemental quality; the poems consider the past and our connection to it, those traces of others passing through before us, whose “footprints” we inhabit. Part I opens with “The Cairn,” in which someone else has marked a spot the poet is passing, as in Frost’s poem “The Tuft of Flowers.” Lyman and Frost are kindred spirits, separated by time but sharing a sensibility. If the piled stones in “The Cairn” could speak, they’d ask their witness “to stay awhile and listen” in a spot “where nobody would think of stopping.” Lyman’s book celebrates ordinary places, and the poems’ silences resonate.

The land has messages for us, and Lyman imbues every inch of it with a face. In “Stone Age,” imagined ancestor visages peer through schist, while in “Side Canyons,” a fossilized handprint extends a ghostly gesture; these encounters are like seeing a mirror in a mirror, endlessly repeating, with something else looking back. They indicate that we are not alone, and also that “aloneness” is, paradoxically, a human condition. This reciprocal glancing is seen again in “The Face Beyond the Faces.” Such poems ask questions that spiral in a reader’s mind: How are we reflected? How are we seen? Lyman contemplates the ways we last and also the temporary hold we have on this earth, as evidenced in crumbling dwellings and overgrown paths.

The poet grapples with trying to get the message, with an almost knowing, as expressed in “Cricket’s Way.” There is comfort found in the near knowledge that kinship with other creatures brings. Obscured paths are a recurring motif—including, in “Cricket’s Way,” a path that “nobody would say might once have been a path.” The cover photo reverberates in “Entities,” in which the space the stars inhabit is “forever ever stretching back towards no beginning / and onwards towards no end.”

Part II begins with “The Dinner Bell,” which rings beyond the page as prayer with its usage of “dome,” “temple,” and “hymn.” We are directed back to a particular past, more personal in nature, but no less fundamental than in Part I. This past is sacred, but still earthy, its “choir” peopled with pigs and chickens. In “Caretaker,” a child’s finger traces turtle miles on a shell, recalling the cricket’s slow travels in Part I.

The bell keeps ringing in Part III, as flute song unravels a “slow dark ribboning” and “unshapen things turned briefly to the shape / of music” in “The Merchants.” Fire, another Lyman totem, laps at the edges of Part IV. In previous sections, fire flickered in images of a burning house and a cupped shared flame; here it smolders in cinders and ash, singed sheet music and burned-out stars.

In Part V, “The Moving Road” echoes the fact that we will only ever almost know, that fractional knowledge touched on earlier. The road image is transposed onto the river, and a later poem in this section uses river and mirror together, twin reverberations throughout the collection. “Photo from Space,” like “Cricket’s Way,” considers the varieties of scale, and “Taken” again explores the partial, the temporal, the eternal search we mount, and the allies we look for.

The final poem, “Land’s End,” rests on that idea of “each of us a world,” and that too is an important thread through the book—the microcosm found in each being, whether cricket, deer, or boy, whether cabbage, turtle shell, vagrant’s suitcase, or pieced-together storybook. Yes, the land has its say in Lyman’s book; the poet has his say, too, and his words are welcome and necessary.