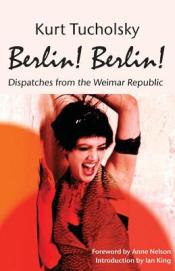

Berlin! Berlin! Dispatches from the Weimar Republic

Kurt Tucholsky

translated by Cindy Opitz

foreword by Anne Nelson

introduction by Ian King

Berlinica ($14.95)

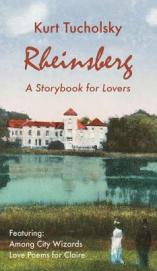

Rheinsberg: A Storybook for Lovers

Kurt Tucholsky

translated by Cindy Opitz

Berlinica ($14.95)

by M. Kasper

In his 1931 essay “Left-Wing Melancholy,” Walter Benjamin criticized three Berlin journalists and cabaret writers by name. “Radical publicists of the stamp of [Erich] Kästner, [Walter] Mehring, and Tucholsky,” he wrote, “are the decayed bourgeoisie’s mimicry of the proletariat.” Their own precious analyses and convictions, according to Benjamin, meant more to these left-wing melancholics than confronting challenges in the real world. It’s a charge that could be leveled at lots of political writers, its author among them. In Tucholsky’s case, at least, it was wrong, or beside the point. He’d been entertaining, informing, and inspiring revolutionaries and progressive artists for years. In 1929 for instance, he and his friend the designer John Heartfield had published one of the 20th century’s most potent and politically-engaged verbo-visual books, Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles, pairing dozens of photos selected from the popular press plus some of Heartfield’s own photomontages with Tucholsky’s sardonic, woefully prescient, anti-military, anti-capitalist, anti-Nazi newspaper sketches.

In his 1931 essay “Left-Wing Melancholy,” Walter Benjamin criticized three Berlin journalists and cabaret writers by name. “Radical publicists of the stamp of [Erich] Kästner, [Walter] Mehring, and Tucholsky,” he wrote, “are the decayed bourgeoisie’s mimicry of the proletariat.” Their own precious analyses and convictions, according to Benjamin, meant more to these left-wing melancholics than confronting challenges in the real world. It’s a charge that could be leveled at lots of political writers, its author among them. In Tucholsky’s case, at least, it was wrong, or beside the point. He’d been entertaining, informing, and inspiring revolutionaries and progressive artists for years. In 1929 for instance, he and his friend the designer John Heartfield had published one of the 20th century’s most potent and politically-engaged verbo-visual books, Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles, pairing dozens of photos selected from the popular press plus some of Heartfield’s own photomontages with Tucholsky’s sardonic, woefully prescient, anti-military, anti-capitalist, anti-Nazi newspaper sketches.

Weimar Germany, with its active, abundant press, has been called the most self-aware culture in world history, and Tucholsky (1890-1935) is widely acknowledged as one of its shrewdest commentators. His form wasn’t new (feuilletons go back to the early 19th century, or earlier), but his plain, urgently ethical yet elegant voice, his concision, his special mix of fact, fun, and opinion were innovative and influential when they first appeared. He was a pioneer of the New Sobriety style of writing, which emerged in response to fevered Expressionism and still reverberates in German and other literatures. His continued relevance is of course also due to the similarity between his society and ours. The greedy capitalists, reactionary judges, and thuggish militarists who populate Tucholsky’s pieces are, alas, as much a part of life now as then.

Over all, over a period of twenty-five years or so, he wrote thousands of sketches and poems. Berlin! Berlin! Dispatches from the Weimar Republic is a welcome addition to the relatively modest number available in English (Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles came out in a beautiful facsimile from the University of Massachusetts Press in 1972, its texts translated by the poet Anne Halley; Harry Zohn edited three successively-enlarged collections of journalism and cabaret pieces, the first in 1957, the second, its cover by Eric Carle, in 1967, and the third, from Carcanet in the UK, in 1990).

Most of the more than fifty pieces in the new selection haven’t appeared in English before. They’re arranged chronologically, approximately, and all have some connection to the city of Berlin (the publisher’s focus). Among the newly available pieces, there are several real gems, including the sad, succinct study of “The Homeless,” the hilarious “The Family” (“The family . . . runs rampant in Middle Europe and usually stays that way”); and “Brief Outline of the National Economy,” a parody beginning “A national economy is when people wonder why they don’t have any money.” Regarding the translation, Cindy Opitz is slightly more fluent than either Halley or Zohn, though occasionally her colloquialisms grate (“dude”; “you’re effin’ crazy”). She does less well with the poetry than the prose, but it’s notoriously hard to present rhyming verse in English; thankfully there are fewer poems here than sketches.

Rheinsberg: A Storybook for Lovers was Tucholsky’s first book, published in 1913, a novella about young love on vacation. It was enormously popular and it has plenty of charm but nowhere near the heft of the mature work. Its breezy style owes something to the writers he then admired, Kafka and Walser, and in fact in that same year a sketch of his appeared alongside the former’s “The Judgment” and a batch of the latter’s creations in Max Brod’s Arkadia Jahrbuch. What’s more, that was the year in which Tucholsky began his long association with the weekly Die Weltbühne, where his style evolved and so many of his most brilliant pieces were published.

Rheinsberg: A Storybook for Lovers was Tucholsky’s first book, published in 1913, a novella about young love on vacation. It was enormously popular and it has plenty of charm but nowhere near the heft of the mature work. Its breezy style owes something to the writers he then admired, Kafka and Walser, and in fact in that same year a sketch of his appeared alongside the former’s “The Judgment” and a batch of the latter’s creations in Max Brod’s Arkadia Jahrbuch. What’s more, that was the year in which Tucholsky began his long association with the weekly Die Weltbühne, where his style evolved and so many of his most brilliant pieces were published.

The first edition of Rheinsberg, actually subtitled A Picture Book for Lovers, is a pretty volume, with line drawings by another Tucholsky friend, Kurt Szafranski. It’s unfortunate the current publisher couldn’t reproduce them. Worse, this new edition and Berlin! Berlin! are both badly designed—bad conceptually, in that the books have been made into cult objects (with random fuzzy photos of everything from Tucholsky at age one to a kitschy pillow in a store selling Tucholsky tchotchkes), and bad visually, in defaulting to the worst habits of low-end printing nowadays: skimpy margins, unattractive fonts, cheap paper, and low-resolution images. As the original Rheinsberg shows, Tucholsky cared about his books’ look from the start of his career. Later in life he said (referring to Heartfield’s designs for his [Heartfield’s] brother’s famous literary press), “If I weren’t Tucholsky, I’d like to be a book jacket for Malik-Verlag.”

Despite this missed opportunity, Berlinica deserves thanks for publishing more Tucholsky in English. Wider recognition among English readers has been slow coming, though it’s clear that we still have stuff to learn from modernist masters of political prose—pace Benjamin—like Tucholsky.