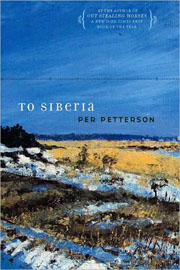

Per Petterson

Per Petterson

translated by Anne Born

Graywolf Press ($22)

by Salvatore Ruggiero

Towards the end of Per Petterson’s novel To Siberia, his unnamed narrator remembers a time when she and an acquaintance she meets on a boat have a quiet conversation before they are about to depart each other’s lives forever:

“I get really melancholy when I arrive at a new place like this. Don’t you?”

“Not exactly,” I said, “this is my town. I was born and brought up here.”

“So you’re home, then.”

Home, I thought, where is that.

With those words, the warmth that one normally associates with a homecoming is torn away and tossed to the wind. The final thought expressed by the narrator isn’t even a question; it is an unfortunate statement, an acceptance that there is no such thing as home: the narrator will always be in this state of instability, ostracized from all.

To Siberia is the story of a woman trying to find a place in the world, a place that even at sixty years of age she is unable to ascertain as she looks back on her life. The novel is a bildungsroman that refuses form, that grates against human attachment, which the bitterness of the title should suggest—and it is in the title that we begin to understand the irony of this novel.

The title comes from discussions the narrator and her brother Jesper have when they are young about what they’ll do when they are able to leave Denmark. Like the little children they are, they yearn for those unpronounceable countries and their foreign-sounding cities. Jesper longs for the warmth of Morocco, “the Arabs’ Morocco . . . Meknes, Marrakech, to the Morocco of the caravans and the Moors.” The narrator, in her naïveté wanting to outdo her brother, says that she wants to go to Siberia. No matter how life turns out for her, she says, she’ll go. But this is a misplaced ambition. She runs her fingers over atlas pages to see Siberia’s vastness and imagines its endless landscape. She desires to take the Trans-Siberian Railroad and thinks of what it would be like to travel from Moscow to Vladivostok by train. When she looks at her mother’s missionary journals, she reads to see if any people within had been to Siberia. To her, Siberia is a safe land where “they wear different clothes and have warm houses built of wood.”

Yet we know better. We know that Siberia is a tundra of unconditional frigidity with temperatures reaching record-breaking lows. We know it is a land of torture; in the era during which the novel takes place, Josef Stalin was driving enemies of the Soviet state into forced labor camps and killing off millions of his own people there. It is not a world a young schoolgirl should be aching for. It is not the land of magic, of mystics, of faeries—all things her brother is dreaming of in his Araby.

Petterson seems to have a laissez-faire position when it comes to structuring the novel, almost as if there is no set configuration. It depicts a sexagenarian looking back on her life’s events, large and small (mostly small), seeing how she got from point A to point B. But it is not a clear or a direct path. Petterson does this through flashbacks and flash-forwards, by letting time and memory become loose, unstable, and non-linear. Like Virginia Woolf, he is able to have a moment seem to linger for eternity, but with much more straightforward prose:

I finish my dance and see myself from above and see myself from the side and take it all in, and it is still quiet as I go to the door and sit on the steps as the light spreads through the street, all golden on the top of the house where Herlov Bendiksen draws aside the curtain and looks out.

Resembling the journey of the narrator’s memory, people enter in and out of her life at random. People die—and that’s the way it is. One day the narrator’s best friend from school, Lone, the girl who is at the top of the class and can understand the narrator’s outsider status, mysteriously exits the novel via death from unknowable causes. The narrator’s grandfather commits suicide for reasons that never seem terribly clear. War—the Spanish Civil War and World War II—suddenly become part of life, entering the lexicon of the locals. And yet, even at a young age, the narrator seems to have come to terms with all of this. She doesn’t whine about her current state. People may be friends or family, but they are never close enough to become fully fleshed-out people. She offers no explanations, and is not interested in the reasons why anymore. She is too tired to piece it all together.

The conversation between the unnamed narrator and the acquaintance on the boat is exemplary of the melancholic and yet unforgiving attitude the narrator and the novel take. It concludes:

I gazed at the quay and the few people there, but it was still too far away to distinguish one from another in the gray light that made all the colors melt together.

“Then you will be met and everything. I’m quite alone, I am. But that’s what I wanted, of course.”

“We’ll see,” I said.

There’s an exasperation, an acceptance of this state of being—alone. For no one comes to meet the narrator at the quay. She has to hunt down her mother and father in order to see them, only to be sharply berated. But so it goes—or, as the narrator would say, “there is nothing left in life. Only the rest.” This is a quiet and beautiful novel of incompleteness, of unfulfilled dreams.