by Nate Pritts

by Nate Pritts

Henry David Thoreau may not be a name recognizable to everyone—painfully, not everyone has read Walden or Civil Disobedience—but his ideas are ingrained in American culture and have defined so much about how we think of ourselves. They set a benchmark still valid today in terms of what we can aspire to as a society and as individuals within that society.

John Porcellino has created a body of work that mirrors Thoreau’s in many ways. I’m not talking about the surface connection of simple and ascetic lifestyles, which Thoreau champions in Walden and which Porcellino documents through his long-running zine King-Cat Comics and Stories. The link between Thoreau and Porcellino is found in the creative work they produce—work that is decidedly American while endeavoring to reshape what the term “American” means.

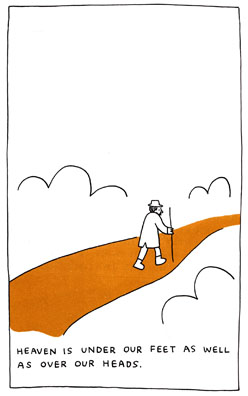

Porcellino’s latest full-length work, Thoreau at Walden (Hyperion, $16.99), represents two philosophies that mirror each other, joining two artists with a similar message presented for different times. Porcellino’s text derives from Thoreau’s landmark book, but his impressionistic vision of the text adds a rich element to it—not because we are able to see the sunsets and wooded areas that Thoreau describes, but because Porcellino is able to enact those contemplative and revelatory moments that punctuate Thoreau’s prose. The result is not merely Thoreau’s message conveyed through another medium, but something wholly new.

In addition to Thoreau at Walden, Porcellino is the author of the acclaimed volumes Diary of a Mosquito Abatement Man (La Mano, 2005) and Perfect Example (Highwater Books, 2000), as well as the compendium King-Cat Classix (Drawn and Quarterly, 2007).

Nate Pritts: Your work is so very personal, which seems largely a function of the simple line style you use. Was it difficult using this style on someone else’s words? Did you find yourself changing your style—or is Thoreau’s voice like an old friend to you?

John Porcellino: Well, I should say that with this whole project I felt a very close kinship to Thoreau’s work. It felt very natural to be working with his words. Also, although I was obviously working with the writings of another person, the book was deeply personal to me. I used my own experiences and thoughts to try to get inside Thoreau’s words. So no, I didn’t really change anything style-wise. . . though, as a cartoonist who mainly works in an autobiographical manner, I think having the main character be “Thoreau”—that is, someone outside myself—helped me loosen up a little bit. It was a lot of fun to draw that beard, for instance!

NP: “Loosen up” in that you didn’t have to worry that people would be judging both the artistic product as well as the life/source material?

JP: I don’t think I thought of it in terms like that, but just. . . As I’ve gotten older I’ve developed a tendency to worry too much, and really tweak every line in my comics, so I can get hung up on that. On this book I felt a little freer to lay the line down and move on. When I started drawing Thoreau, I had just finished up work on the King-Cat Classix book, and maybe looking at the looseness of all that old art rubbed off on me. I think it also had to do with being immersed in Thoreau’s writings at the time—his emphasis on embracing the natural course of things probably influenced me to a degree.

NP: Some of my favorite panels of yours, throughout your work, are the ones where nothing happens—such as the linked establishing shots at the beginning of Thoreau at Walden where we see trees and leaves and big flakes of snow. It’s a really great, contemplative moment, and totally in keeping with Thoreau’s work. Can you talk a little about the importance of these moments from your standpoint as an artist?

JP: In my own life I’ve happened to spend a lot of time out in the woods alone, so in the book I tried to bring that flavor to it. When Thoreau writes about a certain experience, I tried to convey that flavor through looking back on my own life, and bringing out that personal experience. Also, in terms of those moments where “nothing happens,” those are moments that I’ve always tried to convey in my art. Certainly Thoreau had those moments too, like any contemplative person. Walden is a great book of words, but those words came from a certain way of life, an experience of life, a curiosity and wonder. So I tried to show, in simple terms, what that kind of life is like—and in part, that means being open to those moments where "nothing" happens.

NP: My favorite quotation from Thoreau is one you illustrate in exactly this style—“Morning is when I am awake and there is a dawn in me.” You do a beautiful job of letting that hit the reader by following that line with two panels of stillness and natural activity. Reading in context, it’s obvious that Thoreau isn’t talking about just the early AM hours—he’s talking about a kind of mental and spiritual awakening. In your own daily life, when is “morning”—when do the moments of heightened engagement occur?

JP: Like you said, “Morning” in Thoreau’s world is a state of mind, a state of being, and a way of relating to the world. For most of us, that state comes in snippets: little moments of illumination or clarity. You don’t know when it’s going to arrive, or where. But through the practice of opening up, you can prepare yourself to receive those moments.

In my own life I suppose it’s those moments where I lose myself, and a greater awareness unfolds. It can be doing the dishes, walking, in the morning when the mind is fresh, or in the evening when the mind is tired. In fact, this awareness is always present; it’s just a matter of becoming attuned to it, filtering out the distractions so you can see what’s really going on. In some ways Walden is simply a book about how to see what’s really going on.

NP: Place—location and grounding—is very important in some of your early works. But here’s Thoreau again: “Wherever I sat, there I might live, and the landscape radiated from me accordingly. . . there I might live, I said; and there I did live, for an hour, a summer and a winter life. . .” What’s your own relation to where you live—either now or at any time in the past? How has it informed or shaped your work and your creative and intellectual life?

JP: I’d like to think I could be of those people who is “at home” anywhere, like Thoreau describes in that passage you quoted. In reality, that’s hard practice. Thoreau is expressing an ideal, a way of being that improves one’s relation to themselves and the world. In truth we all could say, “wherever I sat, there I might live.” And we all could see that at all times the landscape is radiating from us accordingly. When you are fully present in the moment, as Thoreau is suggesting here, the boundaries between subject and object melt. In those moments there was no separation between Thoreau and “summer life,” or “winter life.” The same is true for all of us; it’s just a matter of recognizing it.

JP: I’d like to think I could be of those people who is “at home” anywhere, like Thoreau describes in that passage you quoted. In reality, that’s hard practice. Thoreau is expressing an ideal, a way of being that improves one’s relation to themselves and the world. In truth we all could say, “wherever I sat, there I might live.” And we all could see that at all times the landscape is radiating from us accordingly. When you are fully present in the moment, as Thoreau is suggesting here, the boundaries between subject and object melt. In those moments there was no separation between Thoreau and “summer life,” or “winter life.” The same is true for all of us; it’s just a matter of recognizing it.

In my own life, that’s something I strive for, but as I mentioned, it’s not that easy sometimes. It takes practice. The circumstances of my life have led me around this country willy-nilly. Sometimes it drives me crazy, and I feel uprooted, scattered. Sometimes it’s not so bad. When you settle into a place, search out its rhythms and hidden worlds, you start to appreciate the specialness of it. I suppose that search is a big part of my creative life—finding that layer underneath that unites and supports.