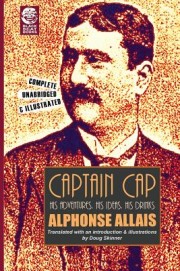

Captain Cap, His Adventures, His Ideas, His Drinks

Alphonse Allais

Translated, annotated, introduced, and illustrated by Doug Skinner

Black Scat Books ($26.95)

The Adventures of Captain Cap

Alphonse Allais

Translated, annotated and introduced by Brian Stableford

Black Coat Press ($22.95)

by M. Kasper

What an interesting coincidence! Recently, simultaneously, and unbeknownst to one another, two different translations of a collection of sketches by the heretofore little-translated 19th-century French comic writer Alphonse Allais were published by small publishers, with similar names no less!

What an interesting coincidence! Recently, simultaneously, and unbeknownst to one another, two different translations of a collection of sketches by the heretofore little-translated 19th-century French comic writer Alphonse Allais were published by small publishers, with similar names no less!

Allais (1854-1905) was a key figure in Montmartre’s Belle Époque, a frequenter of cafés and a frequent contributor to journals like Le Chat Noir and Gil Blas. He’s only half-jokingly called the father of Conceptual Art on account of his suite of monochromatic, hilariously captioned prints, entitled “The April Foolish Album,” and his silent musical composition, “Funeral March for a Deaf Man.” Posthumously, Allais has been continually in print in France and acknowledged as one of that country’s great humorists.

The Captain Cap stories originally appeared in magazines and newspapers, and then were collected into a book in 1902. As Brian Stableford says in his introduction, they “hybridize fictional discourse with mini-essays.” Typically, the narrator and his buddy Cap, a Canadian seadog (and “a useful mouthpiece for tall tales and curious inventions,” as Doug Skinner has it in his introduction), meet up at one or another of the many English pubs and American bars that opened in Paris in the 1890s, and they discuss things—Cap’s far-flung exploits, say, or his philosophical or scientific schemes, or recent technological advances—while enjoying cocktails. One neat and unifying feature of the anecdotes is that many include cocktail recipes, in footnotes, so readers can keep up with the principals. In Skinner’s version, the amusing appendix that appeared in the 1902 edition, repeating the recipes along with pithy comments, is translated; Stableford unaccountably drops it.

Both editions have genuinely erudite introductions and footnotes, but different approaches emerge: for Skinner (a musician and longtime collaborator with artist Bill Irwin), the heart of the matter is Allais’ avant-garde humor; for Stableford (a mind-bogglingly prolific British author of speculative fiction and translator from French), it’s his scientific and pseudo-scientific imagination. Nevertheless both translators—though they rarely choose exactly the same words, and sometimes one, sometimes the other does a better job with wordplay—manage about equally well in capturing the sprightly, ironic, and self-reflexive style that distinguishes Allais. And there’s added value in both editions: Skinner’s—a more handsomely designed book—tacks on eight extra Cap stories that Allais published elsewhere, plus a selection of historical photos, and lots of really charming, apt, and accomplished illustrations by the translator; Stableford’s includes two dozen non-Cap pieces by Allais on related themes—eighty pages worth!—a nice bonus, especially given how little Allais there’s been in English until now.

Both editions have genuinely erudite introductions and footnotes, but different approaches emerge: for Skinner (a musician and longtime collaborator with artist Bill Irwin), the heart of the matter is Allais’ avant-garde humor; for Stableford (a mind-bogglingly prolific British author of speculative fiction and translator from French), it’s his scientific and pseudo-scientific imagination. Nevertheless both translators—though they rarely choose exactly the same words, and sometimes one, sometimes the other does a better job with wordplay—manage about equally well in capturing the sprightly, ironic, and self-reflexive style that distinguishes Allais. And there’s added value in both editions: Skinner’s—a more handsomely designed book—tacks on eight extra Cap stories that Allais published elsewhere, plus a selection of historical photos, and lots of really charming, apt, and accomplished illustrations by the translator; Stableford’s includes two dozen non-Cap pieces by Allais on related themes—eighty pages worth!—a nice bonus, especially given how little Allais there’s been in English until now.

Why is Allais suddenly popular here? Well, he was one of the makers of modernism, admired over the decades by both avant-gardists and a wider public, and with short prose (the Cap sketches are only a few pages each) and stylized absurdist humor now widespread in American literary circles, maybe he’s just due for discovery at last. In any case, these two books are welcome.