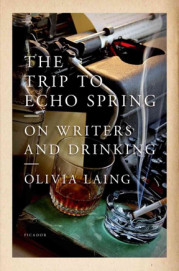

On Writers and Drinking

On Writers and Drinking

Olivia Laing

Picador ($26)

by Matthew Schneeman

In The Trip to Echo Spring: On Writers and Drinking, Olivia Laing emotively employs the works of six great American writers, their biographical content, and her own history in an attempt to dissect alcoholism and the seeming relation it has with writers. Although an ambitious task that deals with cross referencing conflicting biographies, medical opinions, and the paradoxical confabulations that alcohol renders the drinker, Laing succeeds in making sense of this multilayered connection—not with aggressive statements of fact or declarations of authority, but with a gentle confidence that comes from the empathy of her own personal experience and the rigor of her scholarly abilities.

Under scrutiny are authors F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, John Berryman, and Raymond Carver. This collection is comprehensively flavored by the variety of genres these authors worked in—poetry, play, novel, essay—and also in the wide range of personality: Hemingway’s hyper-masculine discipline in contrast to Fitzgerald’s bleeding heart, Williams’ sexual philandering compared to Cheever's isolation. Some similarities are obvious (they are all male, alcoholic, depressive, American) and some less obvious, like the recurrence of love for swimming or the sea, insomnia, fatherly suicide, fires as metaphors, shared locations like Iowa City or the Florida Keys, lover's paranoia. And all of these similarities and opposites are pulled from an equally varied collection of texts.

Laing uses her own trans-American journey from New York City to Port Angeles, Washington to frame the broader historical traipse through the six authors’ successes and failures, both literary and personal. Visiting the homes and haunts of her acclaimed subjects, she constructs as best as anyone can the context that propped up and amplified the disease of alcoholism—be it Cheever's father's suicide, Williams' clinical anxiety, or Carver's crushing economic instability. All catalysts are laid out not as overly simplistic answers to the question of why these writers drank, but as a working foundation to understanding.

Along with the context she creates for our subjects’ lives, Laing also gives us her personal life and feelings through gentle observation; relatable and unassuming, her thoughts are a welcome respite between the chaos and destruction that takes place in the authors’ lives. She subtly notes that her upbringing was “under the rule of alcohol, and the effects of that period have stayed with me ever since." She doesn't pretend this is a medical research project, though she includes compelling research from the Adverse Childhood Research Study and other ideas and theories from the medical community.

Laing does not finish her book with a clear answer to the vexing problem of alcoholism, but throughout the book she cites the Alcoholics Anonymous twelve-step method of recovery as the most effective approach to the disease, discussing the experiences that Carver, Cheever, and Berryman had with the system and their varying degrees of success. Her analysis of the authors who lived before AA was created can come off as less rooted and even a tad anachronistic, though admittedly there was a dearth of treatment options before the twelve-step approach was commonplace.

One immediate payoff from this book is the refreshing de-romanticizing of alcohol among literary giants, as too often are our heroes linked with their addictions as a casual oversimplification. Laing tempers Hemingway's pugnacious literary approach with his thoughts on drinking: “The only time it isn’t good for you is when you write or when you fight. You have to do that cold.” Other examples of the reality of alcoholism include Fitzgerald's regrets on writing much of Tender is the Night drunk, or Cheever's own realization that "To drink oneself to death was not in anyway alarming, I thought, until I found that I was drinking myself to death." By not shying away from woes, embarrassments, and suicides she takes the glory out of the tormented artist and shows authors as people first and heroes second. Perhaps most importantly, she does this without the omission of the beauty and joy of these writers’ lives and works.