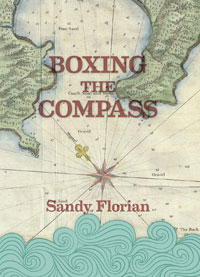

Sandy Florian

Sandy Florian

Noemi Press ($15)

by Peter Grandbois

Sandy Florian’s Boxing the Compass defies categorization, subverts genre, and reframes our ideas of what story and language can do—all the while remaining intensely readable. In fact, upon “finishing” the book, this reader had to read it again. Perhaps a reader doesn’t ever “finish” a book like this, preferring to keep it at hand so that he or she can pick it up on a whim and reread random passages, such as: “she // unfolds her body the same way some people unfold letters from their lovers who’ve set sail, slowly, with caution, minding the curled edges of the cracked pages, that fading blue ink of time,” or “[she] steps onto the // sidewalk turning northeast on that landmass, concrete composite of well and of shell, of hole and of bowl, of buds from that ever budding past, so buckled by history and crumpled by memory, so embedded with remnants of crocodile eyes crying crocodile tears on these crocodile days . . .”

Florian’s work has been compared to Gertrude Stein’s, and the above quotation demonstrates why. However, in the metamorphic power of her surreal landscapes and the mercurial speed of her linguistic transformations, she seems closer to Baudelaire, Bruno Schulz, or Kobo Abe. Florian’s subject is nothing less than the ways in which tragedy precipitates questions of who we are and of what our world is composed. The title refers to naming the thirty-two points of the compass in clockwise order, to make a complete revolution—or, to paraphrase T.S. Eliot, to return home and know that place for the first time. The problem is, how can you find your way home when your world has been thrown into flux? “The only thing she notices as she walks east-northeast to her apartment building is the shape of a dove dead at the entrance, like the shape of a brother, like the shape of a father, like the shape of a mother, a lover, a daughter.” The dead dove opens a gateway to the grief through which the narrator must work her way, a grief that is opening and closing just as the world around her opens and closes.

Life wanes into death, and death waxes into life. The problem is our desire to control the flow, to box the compass: “If she could only live inside this box. If she could only live inside this frame.” We open to one experience only to close off to another, always trying to find our bearings. The structure of Florian’s work beautifully reflects that ebb and flow as each paragraph, each chapter, ends mid sentence, only to pick up with the start of the next paragraph or chapter:

as she gathers herself into the shell of the tub, turning the handles counterclockwise, now hot, now cold, and

counterclockwise again, now hot, now cold,

and spills herself into that ocean predominating this world of ice and fog . . .

Even as paragraphs and chapters pour into each other, worlds collide within those sentences, as the dead dove becomes the brother and the bathtub the ocean. History, science, and geography crash like waves against the narrative as the reader, like the protagonist, tries to make sense of a world in which she is cast adrift: “Don’t be rash little thing. We are all lost on this boat. And the waters are rising higher, rising higher.” Florian’s Boxing the Compass forces us to look at our lives differently. As Pound demanded, she “makes it new.”