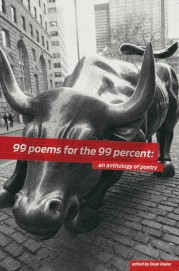

Edited by Dean Rader

Edited by Dean Rader

99: The Press ($16)

by John Bradley

“Some of the great American poetry of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries addresses issues of poverty, class, and capitalism,” writes Dean Rader in his preface to this anthology of poetry inspired by the nation’s continuing economic crisis. “I began to realize,” he continues, “that the aims of poetry and the aims of a democratic country were, if not exactly the same, then profoundly similar,” immediately putting the reader on notice that this is not your usual collection of contemporary American poetry.

In 2011, Rader called for poems on economy, class, and American values his blog 99PoemsForThe99Percent, about the same time that the Occupy Wall Street movement was taking place. The influence of the Occupy movement can be felt in many of the poems here, both directly and indirectly. This provides an urgency to the poems, as seen in Justin Evans’ “Ode to Neruda (Esperanza),” which begins “Because of you / tonight I write / in green ink.” This letter/poem, inspired by Pablo Neruda’s faith in a better future, leads Evans to this blunt assessment:

Mira: I want to believe America is green.

I want to think

America has hope

but I don’t know

if there is enough

green ink in my pen

for all of America.

We are vast like

the blue-green sea

but we despair, languish,

lay weighed down

by our sins. We are

carnivorous dogs

running the streets

devouring everything

that smells like hope.

The poem’s directness, and the affection expressed for Neruda and his ideals, demonstrates what the best poems in this anthology can do—provide insight into our economic woes without lapsing into cliché or easy sentiment.

Ellen Bass’ “My Father’s Day” likewise avoids the pitfalls of addressing economic issues by focusing on her father, who labors, despite physical pain, in a liquor store:

At nine, the drunks are already waiting.

What’s the word? Thunderbird.

What’s the price? Thirty twice.

He slips half-pints of blackberry brandy

into slim brown bags, hefts cases of Pabst

onto the counter. His spine is fused

into a deep curve, neck locked down,

so he has to tip back on his heels

to look you in the face.

It feels impossible to read this poem and not understand the cost of economic inequality. Another poem which speaks volumes on this issue is Jon Davis’ “Preliminary Report from the Committee on Appropriate Postures for the Suffering,” whose title alone warns the reader of what is to come. The voice of authority here informs us that “we have been charged not / with eliminating your suffering but with managing it.” Davis’ tonal control and dark humor fills the entire monologue with pathos.

With a topic as complex as the economy, there are poems here that unfortunately tilt toward slogans. The problem with Erika Moss Gordon’s “Paradelle for the Masses” can be seen in the opening stanza:

We, the ninety-nine percent!

We, the ninety-nine percent!

shouting to one and all.

shouting to one and all.

And the one percent,

all shouting to we ninety nine.

The paradelle, invented by Billy Collins to parody the demands of formal poetry, does not work well here, as without Collins’ satirical tone, the form only intensifies the too-easy emotional stance. Some other poems similarly inspired by Occupy sound like journal entries broken into verse.

The editor of the anthology no doubt would defend these poems by stressing the need for poetic diversity. In the preface, Rader tells us that he looked for “both professional and non-professional poets . . . I wanted to assemble a plurality of writers that showed the range of voices in both poetry and America.” While Rader’s goal is admirable, as well as in keeping with his democratic ideals, it results in a rather uneven collection.

Another problem with the anthology is that the focus blurs at times. There is a poem on the lottery used to draft soldiers for the Vietnam War, one on a Civil War reenactment, one on the Gaza strip, one on how to address a soldier seen at an airport, and one on an unspecified anti-war vigil. While the poems themselves are engaging, the overall effect is of a stew with too many spices. Is the suggestion that economics are at the root of every issue, no matter how removed from the 2008 recession? Or did the editor feel a need to vary the focus at times away from the economy? Some readers may shrug and not care, while others may feel that this is a book overcome by overly broad complaints. Oddly enough, some pundits have noted that one of the reasons that the Occupy movement didn’t endure was that it lacked a single focus. Those involved were united by a broad range of concerns, too broad to galvanize the country. The anthology seems to echo this.

Despite its problems, however, 99 Poems for the 99 Percent still resonates. The poems possess a spirt of defiance and solidarity not often witnessed in American poetry. It can be heard in this line from “The Universe Is Your Country”: “Ten years on the job [at Panera] / and he could not make a loaf / of bread to save himself,” and in this line from “February Was Only Half Over”: “We decided that, after rolling coins, our hands had touched everyone . . .” It can be heard in this statement from “The Product”: “‘What’s going on in this country makes me so upset / that I just feel like I have to go out and, I don’t know, / buy something.’” Even at its darkest moments, this anthology provides hope. In a time of rising cynicism, that’s no small achievement.