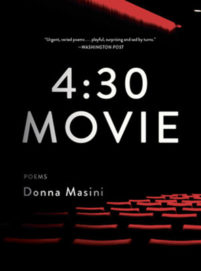

Donna Masini

Donna Masini

W. W. Norton & Company ($15.95)

by Bhisham Bherwani

A figurative meaning of “escape” is “mental or emotional distraction, especially by way of literature or music, from the realities of life.” A survey of such meanings and related criticism informed a 1975 essay, “Escape and Escapism: Varieties of Literary Experience,” in which Robert B. Heilman considered a range of possibilities to which the word could be applied. Though he addressed film as a vehicle of escape only briefly, his commentary suggests an approach to Donna Masini’s elegiac poetry volume 4:30 Movie.

The title references The 4:30 Movie, a genre television program broadcast on ABC in the 1970s that provides an ingenious scaffold for Masini to explore the illness and untimely passing of her sister. Sometimes played out as film, sometimes as film script, 4:30 Movie blurs the boundaries between fact and fantasy, as demonstrated in “A Fable”: “It’s grief’s freeze-framed churchyard / with its fresh-cut dirge, its pretend heaven.” The speaker, in the face of a dear one’s mortal affliction and impending death, straddles external and domestic reality, medicine and prayer, hope and despair, reprieve and frustration, dismissiveness and worry, and denial and acceptance, seen poignantly here in “Deleted Scene: Diagnosis (.23)”:

(Kitchen: Interior)

First they said allergy, then we worried.

Now she’s on the phone with the doctor, motions:

Thumbs Up! Haha, we say. Thumb cancer!

She hangs up. Pneumonia. Hooray!

Pleurisy and pneumonia! Such old-fashioned diseases.

But we’ll take them.

Film tropes provide the poet ample opportunity to escape not only from the horror of the reality before her, but also from memory, from grief, and from poetry itself. But for all the escape hatches at her disposal, Masini’s speaker remains stubbornly obsessed with the matter at hand, spawning a heartbreaking narrative through lyric and dramatic poems that entwine the reader in her emotional complex of anxiety and incredulity, of premonition and superstition. If anything, the premise grounds and contains the difficult subject Masini religiously pursues.

4:30 Movie recalls another similarly innovative poetry book, John Allman’s Loew’s Triboro (New Directions, 2004), also a volume with a New York setting and a sister that employs film as a liminal medium enabling the projection of the real to the imagined, and vice versa. Allman writes, “The movie theater . . . is the place of darkness where lives are expanded and our culture defines itself through its most common denominators.” Masini opens her book with just such a setting in “The Lights Go Down at the Angelika,” a poem in which we see the speaker after she leaves the theater tuned to what is real (“How yourself you are now / walking into the night”), as if reality were unreal: “Apples are more apples. / Paper more paper.”

With her urban, gritty voice informed by irony, Masini’s rapidly unspooling recollections are propelled through flashbacks, pan shots, and close-ups across poems with titles such as “Mind Screen,” “Point-of-View Shot: Celeriac,” “Tracking Shot: Subway Lines,” “Split Screen,” and “Scary Movie.” In her fervent outpouring, her charged tone and resounding keening contrast with a more temperate tone in other poems of loss. This intensity, reminiscent of Sylvia Plath’s, risks pitting linguistic adroitness and naked grief against each other, but this is a risk that Masini negotiates as intrinsic to and necessary for her project, especially given her immediacy to the tragedy.

The middle section of 4:30 Movie is a sequence called “Water Lilies,” which centers on Monet’s paintings where plant and water aspire to aesthetic abstraction. These may provide Masini an escape from form, but offer slim consolation, and no escape, from her loss. But while Masini’s idiom and range of prosody—a sonnet, free verse poems, list poems, even a trailer script—mirror her agitation and the incessant tug of war between affirmation and anxiety, her sister is presented as poised and thoughtful, an unassuming figure gracefully and unobtrusively facing the inevitable. Masini’s departures from her subject, like her speaker’s from the theater, are simply detours and pretexts to return to it, to escape her escapism—which is as illusory and fleeting as that of a movie-goer’s.