Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer

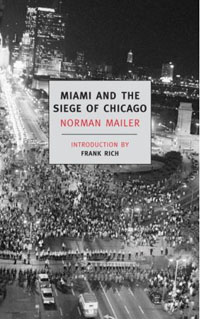

New York Review Books ($14.95)

by C. Natale Peditto

Reading the fortieth anniversary reissue of Norman Mailer’s Miami and the Siege of Chicago, we recognize a writer at the peak of his literary and journalistic talents. This was a period in Mailer’s career that included the remarkably wrought Armies of the Night, which earned both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize; both books remain to this day preeminent, although unorthodox, examples of the New Journalism style. What Mailer accomplished in these titles was to put himself, the author, in direct relationship to the events he was reporting—a third-person observer and simultaneous participant dedicated to revealing the public psyche while unraveling his own tangled motivations and ideology. In Armies of the Night, as the novelist and historian, he writes in measured prose with acuity and strength; in Miami and the Siege of Chicago, as “the reporter,” he is caught up in the pathos of the event.

The 1968 conventions occurred during a historically momentous year of protests and demonstrations, nationally and internationally. In the United States, Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination precipitated riots in over sixty cities around the country; that same month students took over Columbia University campus, and in June, Bobby Kennedy was assassinated. Politically, the Vietnam War augured defeat for the Democrats under President Johnson’s leadership. The Republicans, meeting in Miami Beach, all but staked their future on Richard Nixon—the “new Nixon,” that is, in reference to whom Mailer commented, “America is the land which worships the Great Comeback”; yet in Machiavellian terms he also noted “there had never been anyone in American life so resolutely phony as Richard Nixon, nor anyone so transcendentally successful by such means.” Despite hopeless attempts by the liberal wing of the party to nominate Governor Rockefeller as a way of reclaiming the American electorate, the conservatives prevailed and subsequently claimed the future of the Republican Party. It was the predicable outcome of a lackluster and very conventional convention. Other than the Nixonettes, appareled in their boater hats and modestly clean-cut, down-home outfits, cheerleading, “Nixon’s the one!” (a catch-all phrase that would return to haunt Nixon during the Watergate scandal), much of the convention today is absent from popular memory.

The Chicago convention, on the other hand, evokes remarkable images in the historical consciousness of the nation. Mailer’s reporting from within the confining space of the Chicago Amphitheatre and on the streets and in the bars of the city, as well as from the safety of his hotel room in the Hilton, high above the crowds, is always salient. His analyses and insights tend to revolve around a dominant conceit: “Politics is property” (105), attributed to the liberal New York columnist and delegate Murray Kempton. Mailer makes the metaphor his own, even before crediting its source, harshly critiquing the idealistic supporters of Eugene McCarthy who opposed the corrupt but time-tested political pragmatics that involved “sensuous worlds of corruption, promiscuity, fingers in the take, political alliances forged by fires of booze, and that sense of property (my italics) which is the fundament of all political relations.”

Politics as property is a compelling trope that Mailer uses to maximum effect throughout the Chicago section of the book. McCarthy’s people in their liberal suburban, anti-hippy “clean for Gene” appearance depressed Mailer; Bobby Kennedy was the author’s choice candidate, noting the Kennedys’ “magical” appeal and encouraged by Bobby’s political coming-of-age, “his admixture of idealism plus willingness to traffic with demons, ogres, and overlords of corruption.”

Further references to political property are abundant in Mailer’s analysis; the hierarchy of the political machine dictates “the meanest ward-heeler in the cheapest block of Chicago has his piece.” Mailer is Machiavellian in his discursive style if not in the philosophy of his political prescriptions: “A politician picks and chooses among moral properties”; “politics as concrete negotiable power”; “the true political animal is cautious”; and finally, “the last property of political property is ego.” From a literary point of view, Mailer manages to exhaust his operative conceit.

Mailer indulges in rampart hyperbole, yet his version of events is much more factual when he’s reporting on what transpires on the convention floor and in the delegate caucuses, or when describing the great assembly of anti-war demonstrators in the parks and on the streets of Chicago, which at one point he joins as a speaker. Mayor Richard Daley was the powerful overseer of the main action, from the seating arrangements and control of media and delegate access to the convention hall, to directing orders to the police department to attack the demonstrators. According to Mailer, Vice President Hubert Humphrey’s constituency, of which Daley was a part, consisted of the Mafia and the trade unions at its base. Mailer tells us, “The Mafia loved Humphrey.” While the doves and left wing of the party were confined to the rear bleachers, Daley was down front, holding the floor for the preordained nominee, along with a crew of “hecklers, fixers, flunkies and musclemen. . . . guys with eyes like drills.” But despite Daley’s forceful control, Mailer could assert that it was “the wildest Democratic convention in decades.”

Which brings us to the bloody five-day battle in the streets of Chicago that the nation witnessed on their TV sets. For Mailer, it was a reflection of what was occurring on the convention floor—the older established order in direct conflict with the New Left tilt of the Democratic party, represented in the streets by the young activists of SDS and the Yippies, dedicated to poetry, street theatre and the satiric nomination of a pig for President. Mailer describes the Socialist faction as ideological and confrontational, while injecting a note of ridicule in his view of the Yippies who shunned power for a “politics of ecstasy,” but not without some admiration for their Dionysian music and “tribal unity.” Allen Ginsberg’s great voice of poetry, hoping to appease the beast of violence with a group Om-chant, as Mailer sadly reports, was raw and strained by the tear gas that pervaded the city.

Mailer claims not to be a revolutionary despite his established alliances with the protesters and the persuasive draw of their cause. Confessing a certain closet conservatism, he fears losing his livelihood and life style if the hippy revolution prevails. As a reporter he is off-duty at critical moments, self-consciously arguing his own duplicity behind a drink, and then has to rely on dispatches from various news sources, which he quotes at length, to describe the scenes at the barricades. He can easily envision a final scenario of martial law as the police and National Guard assert their dominance and the call for law and order invades the majority of Americans’ perception of the events. What survives the failure of people power is a crude existential cynicism, Mailer urging “let patriotism and the fix cohabit” and suggesting the idealists depart and leave the pickings to the political gang.

What Americans witnessed that August week in 1968 climaxed on the convention floor as Senator Abe Ribicoff took the podium to nominate George McGovern, the other peace candidate who would return in four years as the Party’s nominee. Ribicoff pointed to “Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago,” confronting Mayor Daley’s shameful abuse of power by alluding to the Nazi Party. Seated down front, Daley rose to his feet along with his goons and shouted to the patrician senator to go fuck himself.

Conventions today are well-scripted and organized down to the smallest detail, the party “brand” set before the public as part of a mass media marketing campaign. Spontaneous demonstrations seem to be a part of the political past. We purposefully demean the “old school” politics that Daley represented as unfair and dirty—indicating an unhygienic and unhealthy mix of cigarettes and booze, cigar-smoking little cheeses pulling strings in the back rooms and making deals with the machine bosses, out of the spotlight of the media. Yet these were the dirty details that intrigued Mailer. Significantly, he opened his report on the Democratic convention with one of the most graphically vivid and visceral descriptions of the Chicago slaughterhouses—an extended description that rivals Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. The way he evokes the smell of death in the air of Chicago that late August is alone worth the price of the read.

The penultimate chapter of Miami and the Siege of Chicago, Mailer’s gossiping with the journalists at the bar as they pronounce their cynical assessments about the future of American politics, is a last call for the author to self-reflect among the petty Mafia in the cocktail lounge, regarding organized crime as the alternative to the military-industrial corporations (“if one had to choose between the Maf running America and the military-industrial complex, where was one to choose?”) and expressions of bad faith when faced with the writer’s bitter task of completing his assignment. These are the final notes of Chicago’s brutal night song, a confrontation with the local police that almost puts Mailer in their clutches for a beating or arrest, or both. Mailer’s parting shot, “we will be fighting for forty years,” is prescient enough and ample reason to take him at his word.

Click here to buy this book from Amazon.com

Click here to buy this book from Powells.com

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Summer 2008 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2008