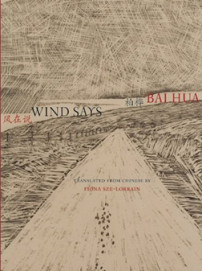

Bai Hua

Bai Hua

translated from the Chinese by Fiona Sze-Lorrain

Zephyr Press ($15)

by John W. W. Zeiser

Bai Hua has only published roughly ninety poems in thirty years, but he is a central figure in contemporary Chinese poetry. His poems are full of the passionate intensity that so often accompanies periods of great historic change, and Wind Says is at once an excellent introduction to one of China’s foremost modernist poets, the turmoil of post-Mao China, and the post-Misty movement, which positioned itself as the most artistically modern of the poetry movements in 1980s China.

Bai’s predecessors, the Misty poets, first coalesced around the magazine Jintian, or “Today.” Founded in 1978 by poets Bei Dao and Mang Ke, its inaugural issue appeared on the Democracy Wall in Beijing. Initially, Chairman Deng Xiaoping encouraged the democracy movement’s “seeking truth from facts,” an overture to the movement that he was serious about reform as he struggled for party control. Jintian’s editors signaled a desire to liberate poetry from party control—what Gu Cheng once called nothing more than “a competition of rhyming editorials.”

While purposely obscure and metaphorical, Misty poetry had a biting, political edge, reacting to the violent excess of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Gu Cheng’s “A Generation” became its clarion: “Even with these dark eyes, a gift of the night / I go to seek the shining light” as the poets sought to wrestle beauty and aesthetics from the party, to liberate the soul. However, in 1980, Jintian was censored for its criticism of the party. By 1983, with Deng’s power firmly consolidated, Misty works were among the “spiritual pollutants” conservative party officials attempted to purge from public discourse. Deng may have loosened economic restrictions, but he and the party had no interest in meeting Chinese intellectuals’ demands for democratic reforms.

But this heady period of experimentation also opened the door for other, less overtly political projects among literary circles. The one that would capture Bai and his contemporaries was one of aesthetics. Interest in l’art pour l’art resulted in the post-Misty school, and by 1986, this third way was in full swing. It was a way in which poetry would free language not from the party, but from its own formal and traditional constraints—it’s no coincidence that Bai trained as a scholar of Western literary history. Much of the theory deployed by post-Misty poets and critics finds parallels with modernist poetry of early twentieth-century Europe and America. Post-Misty poets saw their purview as narrowly confined to language itself, not that which was outside it, much like the New Critics. (Bai, in fact, read Eliot voraciously.)

Translator Fiona Sze-Lorrain, who renders Bai’s uncompromising, discursive style well, notes in her introduction to Wind Says that, according to critic Zhang Di, the post-Misty poets “adopted a nihilistic attitude in public, but in their writing they are in fact able to clearly delineate the tradition they face.” That tradition drew on Misty poets, Chinese modernism during the Republican period, Western poetry, and traditional Chinese poetry. But post-Misty poets saw the act of writing as paramount, not specifically writing poetry. Bai Hua took this to heart and his newest writing follows through on these youthful ideas of “mingling all linguistic genres into one melting pot.”

In Wind Says, we first meet Bai in March 1984, in “Sea Summer.” A year after anti-spiritual purges, “History and skulls fall in flames / Who is warning, burning and wrecking / impermanent sea summer.” Bai’s diction bursts with violent lyricism tinged with hallucinatory incantation. Summer has “fiery hair,” lonely beaches are assaulted by “flying daggers.” It’s the template of his modernist project, full of destruction: “Mood of dusk, feel of blood / destroy finely, destroy willfully.” We are far from the realism of the Misty poets, operating instead on visceral feeling.

Bai’s early poems are often intense and unrelenting in their message. “Or Something Else” makes explicit this new mood in Chinese poetry:

perhaps a huge pore

a tuft of hair standing on end

a patch of fine skin

or a typewriter’s warm voice

could also be a flange knife

Signs and sounds have dual meanings. They are mundane phenomena that also harbor the violent potential of the new, singing with the post-Misty spirit. Rarely in his early work is there a hint of Bai’s inner monologue, only his unmitigated, sensual perceptions as a way to express this aesthetics. In place of a Bai Hua, we are given external personas; cities, seasons, silence, and time that act as characters rather than settings. His writing exudes the conscious sense that the writer is secondary. The words carry the weight.

Bai wanted Chinese poetry to engage directly with the modernism that so frightened party conservatives rather than hark back to tradition. He’s aware of his antecedents, but he keeps them at arm’s length. In “Precipice” Bai concludes, “organs shrivel suddenly / Li Ho weeps / hands from the Tang era will never return.” Bai is determined not to look backwards.

Though the thrust of his project centers around aesthetics, Bai wasn’t immune to the tense political climate of late 1980s China. Several of the poems in Wind Says provide glimpses of this roiling atmosphere, exploding urban populations: “soon, the city had no mass / a true center, masses fight for summer,” hatred that “springs from the flat breasts of ideology.” But even here, his voice remains distinct, saturated with times and places that hang like humid, melancholy memories, “arriving in my life of so few experiences.”

In the ’90s, Bai’s poetry grows sparser, more fragmentary, but also more personal. His sequence of twenty-seven fragments, “Hand Notes on Mountain and Water,” composed between 1995 and 1997, is full of the odd revelations one has revisiting daily scribblings: “Once I wrote a line, Shoot at laughter, / how strange.” They take us to states of mind untethered from narrative or structure. Their succinct observations are the documents of a man growing into middle age:

In Berlin

I grew the first strand of white hair

as a souvenir

Then suddenly he stopped writing poetry; for nearly a decade he turned to other matters. Bai’s output was never large to begin with, and this is a significant gap for a writer so integral to contemporary Chinese poetry. When he finally began writing again, in 2007, his poems had adopted a more reserved, contemplative tone. As if acknowledging his self-imposed silence, he admits, “Life can’t always come in a gush.” More conscious of poetry’s artifice, he begins “Jialing River” with the assurance “Don’t be afraid, this is just a mirror / facing a distant past —.” Gone are the bold proclamations, replaced by a growing awareness of the limits of modernism and a renewed interest in the personal.

Wind Says is an evocative historical document of Bai’s artistic trajectory and the expansion of poetic Chinese modernism. His early work fits the uncertain times of a communist China after Mao. In 1985, he could write without irony that “your dreams are in transition // this is the best moment.” But transitions are only one facet of dialectic and eventually his palette broadened while his artistic zealotry softened. The Bai Hua who wrote those lines in 1985 has become one who could acknowledge in 2010 that “the mourning son is also aging / I have since lost my years of educated youth.”