AUGURY

Linnea Johnson The Backwaters Press ($16) by Ann E. Michael The critical term “unpacking” is undoubtedly overused, but it may be hard to avoid when

Linnea Johnson The Backwaters Press ($16) by Ann E. Michael The critical term “unpacking” is undoubtedly overused, but it may be hard to avoid when

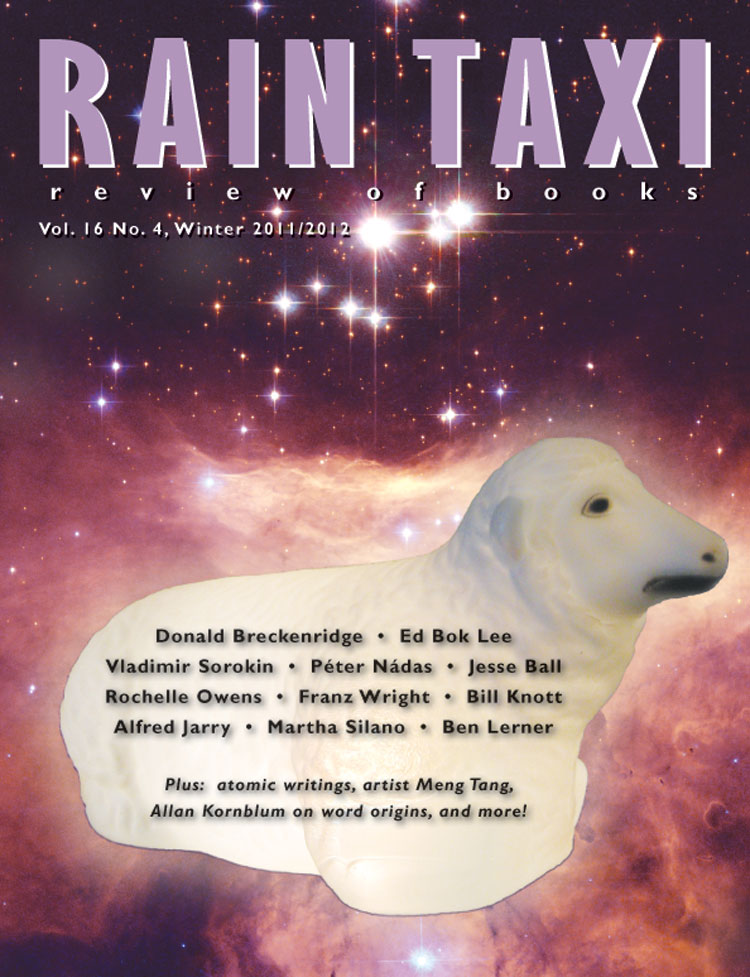

Ed Bok Lee, Donald Breckenridge, Rochelle Owens, Vladimir Sorokin, Ben Lerner, and much more... purchase now

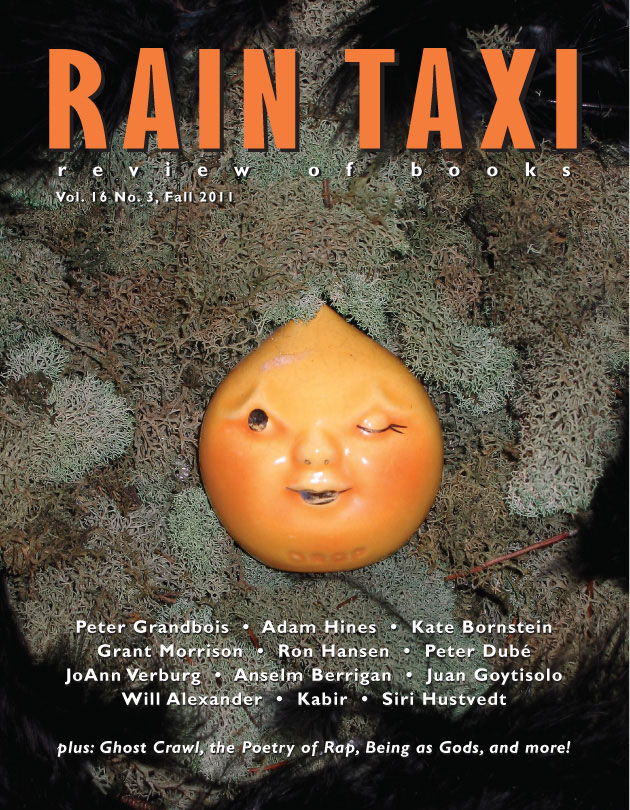

Peter Grandbois, Adam Hines, Grant Morrison, Ron Hansen, Siri Hustvedt, and much more... purchase now

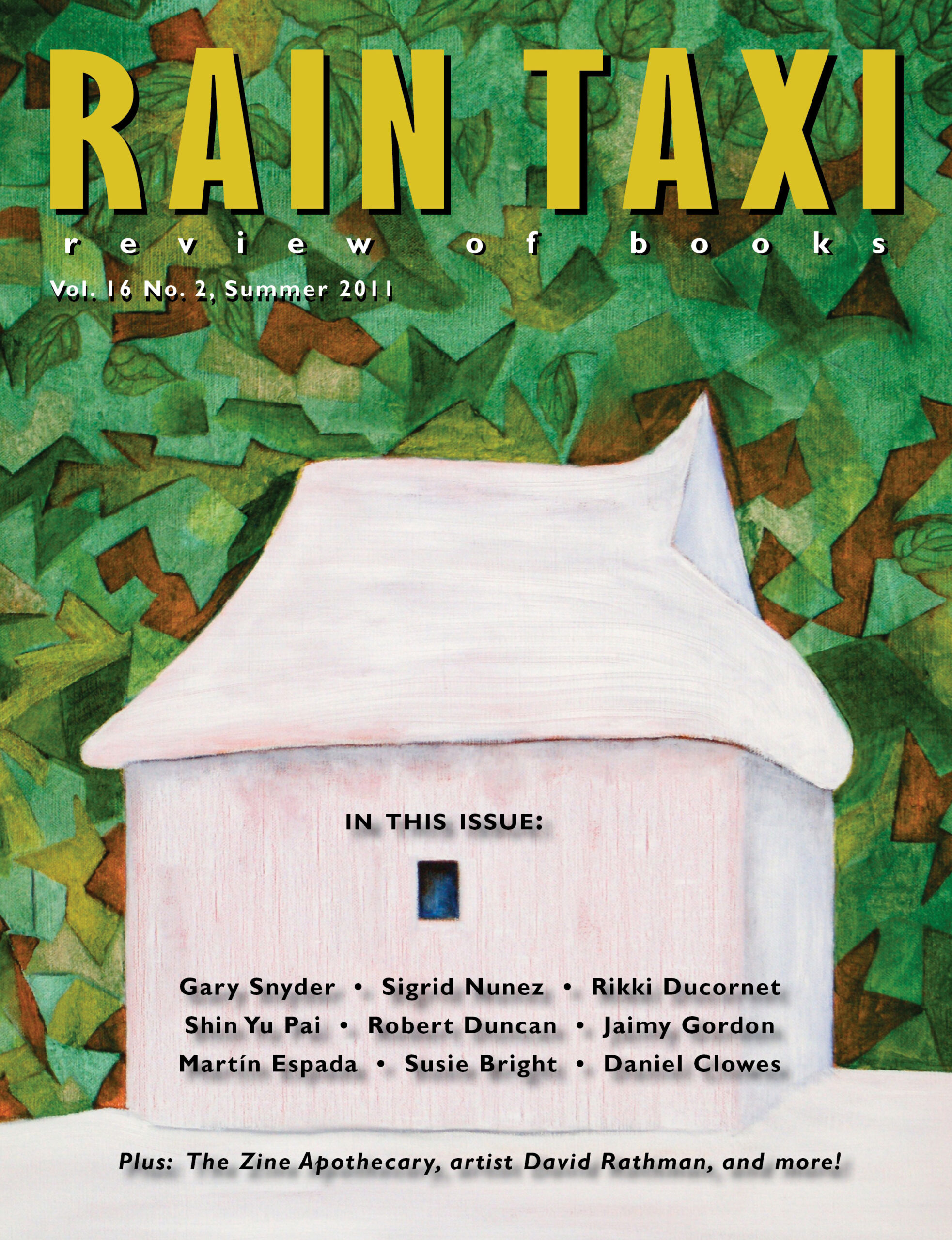

Gary Snyder, Sigrid Nunez, Shin Yu Pai, Robert Duncan, Susie Bright, Rikki Ducornet, Daniel Clowes, and much more... purchase now

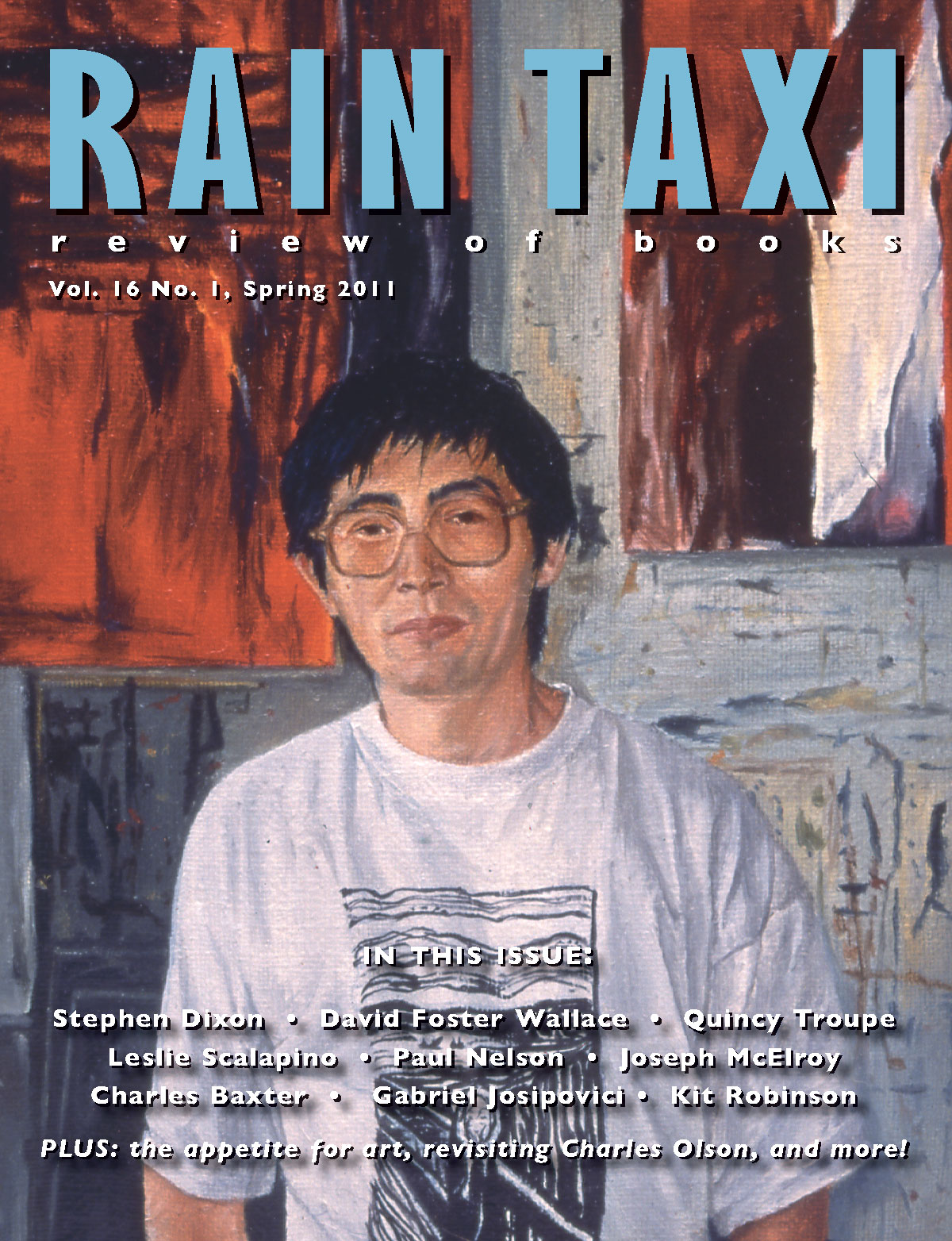

Stephen Dixon, Leslie Scalapino, Quincy Troupe, Paul Nelson, Joseph McElroy, and much more... purchase now