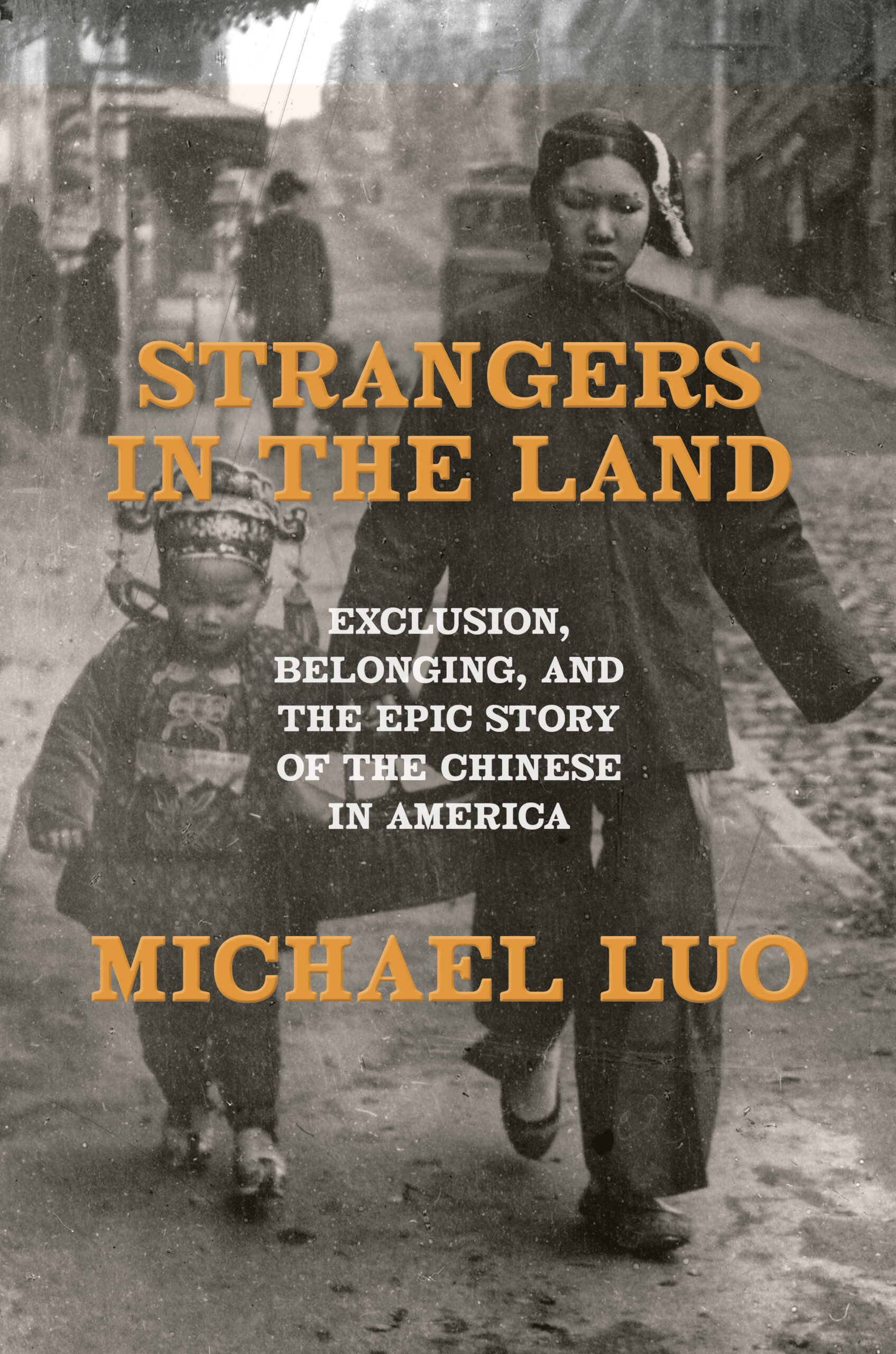

Exclusion, Belonging, and the Epic Story of the Chinese in America

Michael Luo

Doubleday ($35)

In October 2016, an “Open Letter to the Woman Who Told My Family to Go Back to China” appeared on the front page of The New York Times. Its author was Michael Luo, an American-born journalist of Chinese descent. In this letter, he expressed his amazement when, as his family was waiting outside a Korean restaurant in Manhattan’s Upper East Side, a passer-by, frustrated at having her way obstructed, screamed at them, “Go back to your fucking country.” Luo’s seven-year-old daughter was confused. “Why did she say ‘Go back to China?’,” she asked her parents. “We’re not from China.”

In Strangers in the Land: Exclusion, Belonging, and the Epic Story of the Chinese in America, Luo attempts to answer his daughter’s question. He offers a history of anti-Asian sentiment in the U.S. that chronicles the persistence of the disorientating demand “to go back to where we came from.” The book, which Luo presents as “the biography of a people,” focuses on the stories of individuals. It’s a compelling approach, and one which was evidently not without its challenges: Luo acknowledges that archival evidence detailing the specific stories of Chinese arrivals is limited. By combing primary sources and drawing on existing historical studies, however, Luo accomplishes an impressive feat. Arranged chronologically, his stories reveal how successive generations of Chinese immigrants sought belonging in America despite programs of systematic exclusion.

From Gold Rush-era San Francisco of the 1850s to the present-day streets of New York, Luo argues, Chinese immigrants have been made to feel like “strangers in the land.” He explains at the outset that one of the founding principles of America was the intention to celebrate the “multiplicity of difference,” yet hostility towards the Chinese has often been directed precisely at their difference—the language, mannerisms, customs and dress that mark their distinct heritage. A recurring detail in the book is the queue (the braid required to be worn by male subjects of China’s Qing dynasty), and how many arrivals cut it off to approximate a more American appearance. It rarely helped. In 1889, defending the upholding of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Justice Stephen Field described the Chinese as “impossible to assimilate with our people.”

The most interesting chapters of Strangers in the Land home in on a particular group of Chinese immigrants and then explore, through the stories of individuals, the friction that developed between them and native citizens. A chapter entitled “Lewd and Immoral Purposes” reveals the challenges faced by Chinese women arriving in the mid to late nineteenth-century. Until this time, the vast majority of Chinese arrivals to the U.S. were men seeking employment as laborers on the railroads and in Californian Gold Rush towns. Many of these men had wives and family in China to whom they intended to return after making their fortune. As Chinese communities became more established, however, women started to arrive.

Chinese women were met, Luo tells us, with “near-universal opprobrium,” and for one reason in particular: The bachelor demographic of Chinese quarters made prostitution a lucrative enterprise. Ah Toy, a woman from Canton who arrived in America at twenty years old, was an early adopter of the profession in San Francisco’s Chinese quarter; setting up shop in “a shanty in an alley off Clay Street,” she offered men “a chance to ‘gaze on her countenance’” in return for an ounce of gold dust. She began employing other female arrivals and opened brothels in at least two locations. Trouble began to brew as rival tongs (the secret societies that vied for influence in the Chinese immigrant community) sought to seize control of the burgeoning sex trade. City officials, meanwhile, delighted in finding a pretext to indict the Chinese community as “an alien, heathen people,” then collaborated with Protestant missionaries to push for an outright ban on the arrival of women from Asia. They all but succeeded: In 1870, a state law was passed that forbade Asian women from entering without proof of “correct habits and good character.”

Luo’s book makes clear that legislation which systematically excludes Chinese immigrants has been a recurring event. It reached its apex in 1882 with the Chinese Exclusion Act, a U.S. federal law that prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers for a period of ten years and denied naturalization rights to Chinese residents. This was the first time that the United States barred a people from immigrating based on their race. Luo makes the reader feel afresh just how shocking this is by highlighting the zeal with which white Americans sought to oust Chinese people from their communities. Homes were burned, shops looted, men violently attacked. If the Exclusion Act did not exactly sanction such activity, it emerged from a similar underlying attitude.

Strangers in the Land is an important book, not least because it resonates uncomfortably with current headlines. The deportation of immigrants to penal colonies in El Salvador is just one instance of the alarming persistence of hostility and even violence as a strategy for reckoning with “difference.” As Luo puts it, his book is “not just the story of the Chinese in America; it’s the story of any number of immigrant groups who have been treated as strangers. It’s the story of our diverse democracy. It’s the story of us.” Belonging, Luo shows us, is a fragile thing, and it depends on respect and dignity. He dedicates his book to his daughters, hoping that they may find the belonging that continues to elude him. We’re left lamenting, however, how far there is still to go.

Click below to purchase this book through Bookshop and support your local independent bookstore:

Rain Taxi Online Edition Summer 2025 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2025