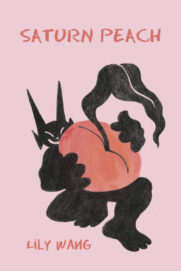

Lily Wang

Lily Wang

Gordon Hill Press ($20)

by Greg Bem

“I am rowing away from myself into myself,” writes Lily Wang at the start of her mesmerizing collection Saturn Peach. A five-sequence book of poetry rooted in memory and reflection, inquisitive imagery, and minimalist tones, the book contains just over 80 pages that repeatedly suggest how questioning can lead to truth, growth, and transformation.

In an early poem, “The Christian Cycle / Redemption / Etc,” Wang writes:

Let Eve kill herself or what of her daughters?

Daughters aligned like beads on a horizontal

plane. Hearts skewered on the vertical

axis of your judgment.

What cycle?

This exemplifies how the poet explores the experience and mythology of womanhood vis-a-vis violence. Wang’s writing begins with the source and examines it from every angle. The questioning is both caustic and critical, enveloping statements of vigilance and liberation. Wang implements her technique subtly, in short, stark, surreal poems, often bridging into prose or breaking apart for rambles; the result feels a bit like Kim Hyesoon, though entirely unique as well.

Wang’s mixture of complex and simple language accommodates the tension between a fixed reality and a more radical, though amorphous, realm of possibility. Time and again in these poems, the slate is washed clean. “There is always something in my eye. I just forgot. I must be late for / something. I forget,” Wang writes in “Having a Thursday Morning.” Here epiphany meets longing, but Wang consistently goes deeper to root out what change could be possible, as in “S”:

I love the highway at night, it’s that simple

it could be so simple. Someone honks their horn

and I go to open the door, to fight, then my friend

says her heart is an overripe peach

The poet is energetically concerned with the past, with history, always moving backward and forward through time. Occasionally this transportation feels emblematic of a curse or a burden, which leads to a threshold of both repression and calm: “7 months and still grieving the setting sun. // 7 months and still looking back, watching you turn to stone.” This suspension raises questions, and yet the mystery elevates experience through curiosity, suggesting abundance through lack and evoking potential through emptiness.

As Saturn Peach moves forward through its sequences, the most holistic, stable literary element that emerges is the book’s structure itself: the five sections that Wang uses to house these poem-canvasses. Wang harnesses image through experiences of her daily life, portraits of friends, ekphrastic examinations of classic (and often violent) films, and even an homage to Anne Carson. Yet the overarching structure, the book’s five stable sections, feels simultaneously distant and present, faded and yet ripe with intense remembering.

Ultimately, it is the feeling of distance that provides a powerful challenge to the reader. Like walking into an art gallery filled with minimalist paintings, the reader of Wang’s poems has been provided an opportunity to feel confounded by the imposing leftover of potential. It is a defiant and wandering process, even when Wang writes, “There is a simple direction to /everything.” This truth is as frustratingly straightforward as a Zen koan, and yet it is critical and feminist, bringing reality into question to ensure that questioning occurs.