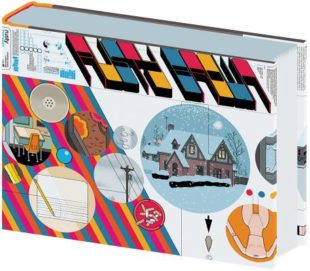

Chris Ware

Pantheon Books ($35)

by Steve Matuszak

Rusty Brown, the eponymous character of Chris Ware’s masterful 2019 graphic novel, first appeared in 2001, in the fifteenth issue of Ware’s comics periodical The Acme Novelty Library. If he were a person born that day, Rusty might now be finishing his first year of college, perhaps thrilling with anticipation at voting in his first presidential election. But that is unlikely, given the disheveled, emotionally stunted adult Ware depicted in the series of short strips scattered throughout that issue: the self-appointed “Midwest’s number one ‘Happy Meal’ collector,” whom we see taking a bath with Looney Lemon, a Funny Face figurine given to him by his loyal, and only, friend Chalky White. Rather, he would probably be flaming people who defended the unexpected plot developments in The Last Jedi on a Reddit Star Wars forum, or obsessing about getting his hands on a long-tailed Rapunzel to inch his vintage My Little Pony collection toward completion.

Granted, the adult Rusty would have different cultural reference points than the more contemporary counterpart I’d just imagined, but it doesn’t matter. Despite our initial encounter with him in 2001, the adult Rusty is nowhere to be found in Rusty Brown. The chapters that make up roughly two-thirds of the novel are devoted to characters other than Rusty, each chapter named after the character on which it centers. Almost perversely, the chapter in which Rusty, an eight-year-old boy, appears at length is titled “Introduction,” which Rusty shares with Chalky White and his sister Alice, two new students at the private seminary that Rusty attends.

Even more perversely, the word “Intermission” is emblazoned in capital letters across two pages immediately after the conclusion of “Joanne Cole,” the final section of Rusty Brown; arguably the most moving narrative in the book, it portrays the life of an African-American grade school teacher in Omaha, Nebraska, where the graphic novel is set. On their website, Pantheon lists Rusty Brown as “part one of the ongoing bifurcated masterwork.” But should this prove not to be the case—is Ware invested enough in this cluster of people to devote more years to them, and is he confident enough that readers will stick around that long?—it wouldn’t be as troublesome as one might imagine.

For Rusty to vanish in his own narrative would be consistent with a boy who comes most to life when he’s a fantasy version of himself, his alter-ego Ear Man—the superhero Rusty dreams up when he suspects that he might have extraordinary hearing powers after overhearing his parents arguing about him even though he was outside in the driveway wearing a thick hat. But Rusty is no superhero. To pick up a metaphor that runs throughout the book, Rusty is a snowflake. As the narrator of the opening two-page spread of snowflakes informs us: “The exquisite, miraculous shape of a snowflake is a result of the singular path it takes through utterly unique conditions of cloudiness, temperature, and humidity, a veritable picture of its whole life from its birth as a speck of dirt to its end as a fragile miniature crystal flower.” The speck of dirt hardly captures the essence of the snowflake. Rather, it is the journey the speck of dirt makes, the conditions through which it passes—conditions that themselves are ephemeral, with no two moments the same, to borrow from the truism. The snowflake is the expression of everything that went into its appearing in this particular form; it’s not a thing separate from those conditions. Not to understand that is to miss what a snowflake actually is. Like a snowflake, Rusty can’t be reduced to what lies at his core.

For Ware, this aspect of being—how its very essence, its aliveness, is not reduceable to the thing itself but is an expression of the totality from which, of which, and in which, it appears—accounts for the aliveness of comics. As he observed in his 2017 book Monograph:

The universe . . . is almost assuredly a continuum through which our consciousnesses pass, its (and our) shapes knowable only in the slices of time and memory we experience and cling to as fragments of a three-dimensional present. Not to draw too much of a bold line under it all, but in somewhat reduced form this notion undergirds the idea of the basic structure of comics, where the composition, the rhythms and the rhymes are more important than the individual pictures and panels themselves.

By extension, Rusty isn’t to be found by scrutinizing some person named Rusty Brown, but in the rhythms and rhymes that create him. By not looking directly at Rusty we see him most clearly, an insight that informs the structure of Ware’s graphic novel. After the “Introduction,” the narrative is broken up into three chapters that focus on people in Rusty’s life: “William Brown,” Rusty’s father, a teacher at the private school that Rusty attends; “Jordan Lint,” an older boy at Rusty’s school, who bullies Rusty; and “Joanne Cole,” Rusty’s teacher, one of the few African Americans at the school. All provide the conditions that shape who Rusty will become—the emotionally-stunted, selfish, socially inept collector we first met in 2001, but who is nowhere directly seen in Rusty Brown. It is through them that we see Rusty, rather than by observing the wildly inappropriate behavior he engages in as a “grown man.”

In its nuanced observations of human behavior—observations that deploy a dazzling array of comics techniques, ranging from the fairly traditional to the formally daring—Rusty Brown continues exploring the artistic terrain Ware established with Jimmy Corrigan: Smartest Kid on Earth and Building Stories, his previous graphic novels. In subject matter and format, Rusty Brown more closely resembles Jimmy Corrigan, whose protagonist, like Rusty, is a socially maladroit loner who frequently slips into vivid fantasy worlds, often involving superheroes, to negotiate his difficult life.

All of Ware’s narratives, no matter how claustrophobic they seem, open out onto other lives and times, employing a wide range of cultural references and inventive representational strategies. In fact, it is in its formal playfulness and experimentation that Ware’s work is most pleasurable. The most formally virtuosic chapter of Rusty Brown, “Jordan Lint,” relates the entire life of its title character in eighty pages, each page a year in Lint’s life. Highly abstract shapes and forms that suggest human faces coalesce into the more conventional iconographic cartooning style that is Ware’s “degree zero,” the evolving style mirroring the development of Lint’s consciousness. Its effect is similar to what James Joyce did in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the book’s prose transforming from the rudimentary syntax of a child to the abstruse prose of an ambitious, young intellectual.

Probably the riskiest chapter of Rusty Brown, at least in an era in which the question of who is and who should be telling whose stories is rightly contested, is its least explicitly audacious in terms of form: “Joanne Cole.” Recounting the life of a Black woman in a predominately white community, the chapter spans the latter half of the twentieth century, detailing Joanne’s life in all its small triumphs and failures, as well as in the daily racism she endures, the offhand comments—when not outright slurs—and condescending attitudes. For example, a music store owner, upon first meeting her, is clearly uncomfortable when she asks to rent a banjo, an instrument that is so inexpensive his store usually doesn’t rent them, and that he associates with white music, asking her at one point, “So how’d you get interested in the banjo, anyway? ‘Protest songs’? Ha ha.” He is seemingly unaware of the banjo’s African roots, reflecting white America’s assumptions about most things American, their roots in African traditions blanched by true color blindness rather than the imagined kind used to disavow racism.

What drives the chapter’s narrative is an absence, echoing the adult Rusty’s absence from the graphic novel. What is missing for Joanne is not spoken of until the chapter’s poignant conclusion, devastating in the understatement with which Ware renders it. But in its closure, “Joanne Cole” also suggests a new chapter in Joanne’s life, making it a perfect conclusion to Rusty Brown, a book that ends with an overt statement that it is not yet the end.

And just as the novel transcends itself at its conclusion, Rusty transcends himself too, at least the self that is the speck at his core, or rather, the novel’s core. If the adult Rusty is missing, he can be seen in the shape of his absence, perhaps even more clearly than had we been able to look directly at him.

Moreover, getting fixated on a narrative featuring a protagonist is a plague of western thought, according to Rusty Brown character Chris Ware—who looks suspiciously like the celebrated cartoonist Chris Ware, except that this Chris Ware is a pretentious high school art teacher instead. “Ware” cites the also fictional critical theorist Arnold Martin—“PRONOUNCED AR-KNOW MAR-TAN,” Rusty Brown’s nameless narrator tells us—who, as “Ware” informs his colleague William Brown, “attributes this modern feeling of ‘weary dislocation’ to the western predilection for a protagonist . . . a ‘main character’ . . . I mean, how can anything go ‘wrong’ when you’re the star, right?” “Ware” refers to how making ourselves the protagonists of our own stories blinds us to our relative powerlessness in the face of a universe that can then seem to be working against us, which can provoke in us a profound sense of malaise. But in turn, couldn’t Ware be releasing the reader from the need to anchor the narrative of his “ongoing bifurcated masterwork” on a protagonist, freeing the reader from malaise, and opening the novel out onto the bigger picture, so to speak, the whole composition of life itself, whose rhymes and rhythms, manifested in Rusty Brown, ripple outward back into its depths?