by Rose DeMaris

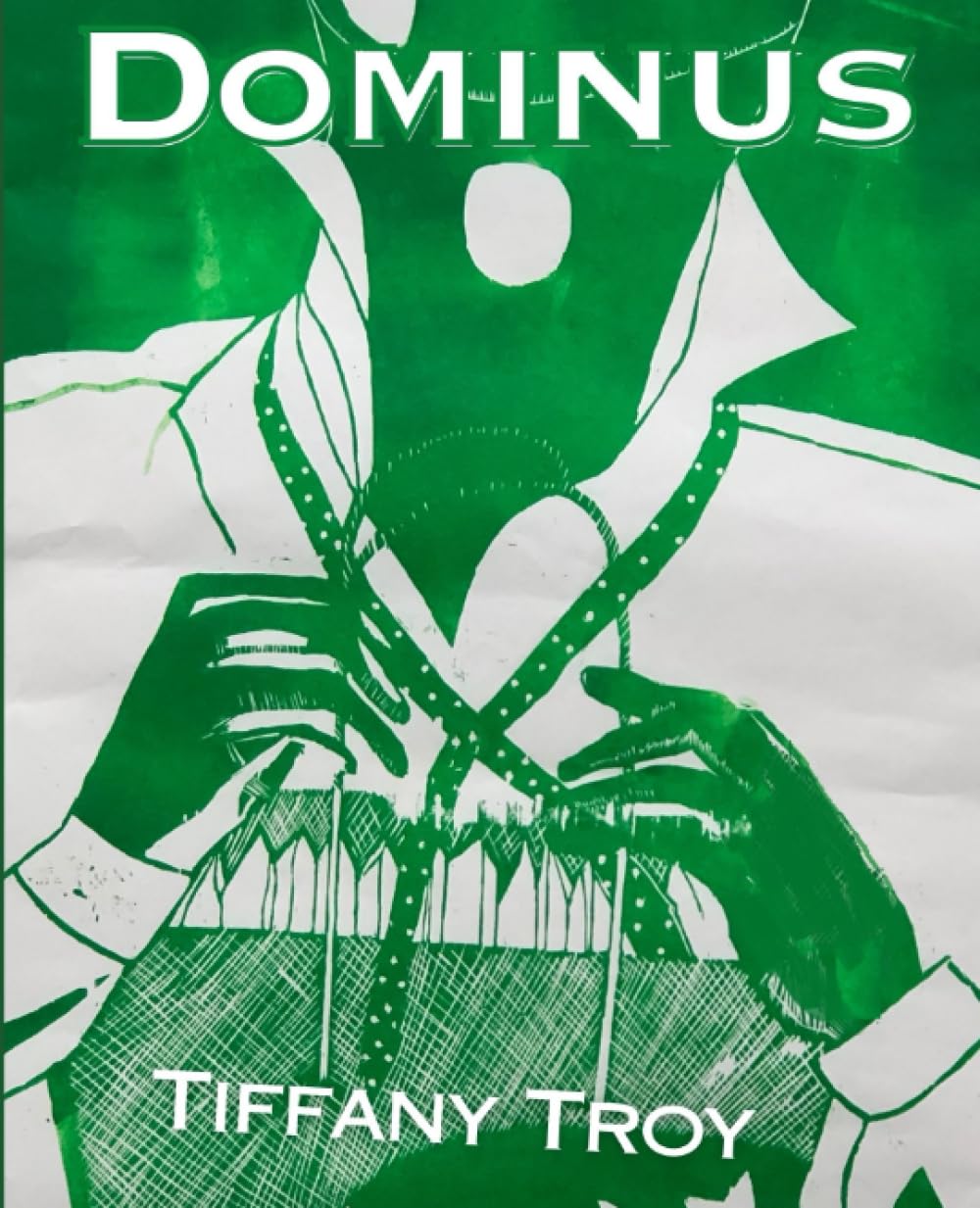

To open Dominus (BlazeVOX, $18), Tiffany Troy’s full-length poetry debut, is to enter a world that is both recognizably earthly and potently mythic. Here, the epic, eternal essences hidden within the most prosaic acts (consuming ketchup), scenes (arguing in a courthouse), and relationships (familial or otherwise) are revealed through Troy’s alchemical mix of voice and form. The book’s speaker is an honest, sharp, and subjugated “I.” Sometimes she is “Baby Tiger” and sometimes a “tamed wolf without fangs” beaten down by the cruelties of capitalism, corporate America, and paternal masters both human and divine. An overworked attorney, she’s the daughter of an immigrant father and a faraway mother who, despite feeling at times like “every girl who ever thought / maybe she had wronged the world by existing,” retains a capacity for incisive observation, keen feeling, and adaptive mutability fueled in part by “life-affirming brekkie” and steaming cups of Earl Grey. Troy’s poems never hover delicately above despair; indeed, there is a deep and wondrous aesthetic refreshment in their refusal to do so. And it is precisely “through the thick residue of the window pane” that her lines reveal light, and become it. Baby Tiger is akin to one of autumn’s “frowning sunflowers burdened / by the weight of their golden mane” who “cannot help / but peek up and beam.”

In addition to Dominus, Troy is the author of the chapbook When Ilium Burns (Bottlecap Press) and has published her poetry, criticism, and translations (primarily of Latin American women writers) in numerous journals and anthologies. She is Managing Editor at Tupelo Quarterly, an Associate Editor at Tupelo Press, and Book Review Co-Editor at The Los Angeles Review.

Rose DeMaris: The sense of place is so vivid in this book. “Ilium” is a place name used in Dominus, but it includes a broad spectrum of settings, from Flushing, Queens and Burger King to apartment interiors and subway trains. It’s a kaleidoscopic world you’ve built with words. How does your own relationship to “place”—whatever that might mean to you—and to New York City inform this work?

Tiffany Troy: Dominus’s sense of place derives from the exuberance of a speaker in a city that feels new and full of possibilities—it is impossible for her not to geek out at the tiramisu at Columbia University or the double whopper at Burger King, chase after the mallard ducks at Flushing Meadows Corona Kissena Park, and take in the metallic sheen of the Gowanus Canal and the glass bottles at Dead Horse Bay in Brooklyn. Kenneth Koch begins “To My Twenties” with the lines “How lucky that I ran into you / When everything was possible,” and Dominus is informed by that bubbly sense alongside the neoclassical architecture of the courthouses, which are solemn and meant to establish awe. This is the setting where the characters grow up, a world where the corporate and professional coexist with the natural.

In thinking about Ilium as “place,” Dara Barrois-Dixon recently sent me “Kurt Vonnegut’s House Is Not Haunted” by Sophie Kemp in The Paris Review. In this essay, Kemp writes:

Slaughterhouse-Five is set in Dresden and Luxembourg and Outer Space and also Ilium, New York. Ilium, it is argued by most Vonnegut readers and scholars, is probably Schenectady. It appears in several of his other books. Player Piano, Cat’s Cradle, and a few different short stories. Here is how Ilium is referenced, in one passage of the Slaughterhouse-Five: “Billy owned a lovely Georgian home in Ilium. He was rich as Croesus, something he had never expected to be . . . In addition he owned a fifth of the new Holiday Inn out on Route 54 and half of three Tastee Freeze stands.”

What a coincidence, right? As with Vonnegut, my Ilium is drawn from the rich cultural heritage of a town I’m familiar with, and it focuses on its identity as an ethnic enclave from the insider’s point of view.

Place is critical to the development of some characters who are “out of place,” being immigrants or children of immigrants. Transportation literally moves people to and from jobs—the seven train runs from Flushing-Main Street to Times Square-42nd Street, for example, while also reinforcing the hierarchy of the boroughs: Manhattan is glamorous with its skyscrapers and Museum Mile brownstones, Long Island with the Hamptons and foliage at Oyster Bay.

Chun Wai Chun, principal dancer of the New York City Ballet, recently shared a reel that began: “You think all the Chinese boys run laundries and are watchmen when they grow up? We want to be policemen, firemen, soldiers, doctors, lawyers, and sellers.” I identify with that statement and its double-bind maze of what we colloquially call the “American dream.” As someone who grew up in Queens and traveled to school in Manhattan, I am interested in writing Dominus to capture that sense of never-belonging in tandem with light.

RD: Ilium is also, of course, another name for the ancient city of Troy, a real place that is also part of Greek mythology. And there is a mythical quality to the way you work with names. The speaker is sometimes named Baby Tiger, or Shepherd Girl, or Little Maria (she identifies with Saint Maria Goretti). There’s also Master, the father figure to whom the book’s Latin title refers, and Grandpa Pindar, Friend, The Nurse, The Doctor, etc. Sometimes you use familiar terms like papa, mama, brother, grandma. And sometimes you use people’s actual names, like Ilya Kaminsky, Monica Youn, or Machiavelli. How does naming or not naming people work to propel your writing? Do the pseudonyms free you up a bit by providing some distance or a playful quality?

TT: The speaker’s various alter egos (“Baby Tiger,” etc.) are popular with readers, and the diminutives (“baby,” “girl,” “little”) in the two-word nicknames aid in creating a sense of endearment, or a proximity with that which is at once familial and youthful. There is something epic or heroic about the speaker figuring her way out of the Wonderland of the court, hospital, church, or corporation, where the bureaucracy has adopted its own lingo that often conceals what is truly meant. Characters with titles as names, like Friend, Doctor, or Nurse, explore the perils of taking that abstraction in corporate-speak too far because in treating people as statistics or resources, the characters literally become their title or position. Then Grandpa, Mama, Papa, and God, are blood or adoptive family that ground the speaker. They are wiser than the speaker in that they have experienced the world which has both “made” them and “maimed” them in some way, to borrow Margo Jefferson’s term for it from Constructing a Nervous System. Mary Jo Bang calls Maria Goretti a kind of “icon of pure goodness that acts as talisman,” and I feel Grandpa Pindar and Mama especially fulfill that role; their kindness is imbued with their personalities as the speaker’s fictional family pays homage to their role in the literary pantheon.

The specific names referenced stem from that same aesthetic consideration of the New York School, where names are the “violets that cannot be pinned upon the crucible.” Naming people there, like naming mythological characters, creates layering in this fictional city of Ilium where the imaginary (Procne), the historical (Maria Goretti), and the present (Monica Youn, say) can coexist.

RD: The lines in which Monica Youn features are memorable and moving, as she appears as a source of comfort: “what must I do to find my Goldacre / besides downing a Hostess box. / But I have waved goodbye to my sweet tooth, and // all I feel is my body, parts of it, like my thumb / in my mouth / my fingers pulling up a video of Monica Youn, / my wet ears on my phone, as I rock myself with shut eyes.”

This leads to another facet of your book I’m curious about: its abundance of food. From clam chowder and bagels to sausages and diced fruit, the food in these poems has many dimensions: it’s a source of nurturing (“Master feeds me at the red lights”) and of relief from pain: “each day I come up with an excuse for my sugar larks and plunges.” A Twinkie is “a Key to our repressed psyche,” and eating can be a means of psychological survival—”I swallowed to not be swallowed”—or an expression of ire: “I gobbled down two sweet clementines aware that my rage // was bubbling up.” Sometimes it’s tied to moments of humor: “Baby Tiger’s Adversary took a long nap from food coma after lunch.” Food is a link to culture: fish is “laced with emerald /. . . in fortuitously red plastic bags” at the Chinese market, while ketchup is a “symbol of solid American pragmatism.” And it’s a link to “memories of downing defrosted frozen fruits, their sugar already gone” and to a longed-for mother “frying rice with a smile” on “iPad wallpaper.” Food is sustenance received—”warm hot Swiss Miss”—or eked out, to the detriment of the giver: “I squeeze my breasts for milk / before collapsing from fatigue.” Even the speaker and her father are described as the “tongue” and “teeth” who must work together; the relationship at the very heart of the book is like a mouth. Can you talk about why all these edibles and moments of eating found their way into your poems—is there a relationship between consuming, digesting, releasing, and poetry?

TT: I have been a huge fan of Monica Youn’s poetry for close to a decade, and she has been a role model of what Asian American poetry and law poetry (or poetry by lawyers) can look like. I of course owe the idea of the “Twinkie” to her Library of Congress reading of “Goldacre” from Blackacre.

Food is tremendously important in Dominus because it is the nexus between the thinking speaker and the speaker as animal. The need to eat literally stops work. Baby Tiger, Little Maria, and Shepherd Girl are united in their love of chocolate and fast food. In one way, that makes perfect sense, because somehow these characters believe that by consuming the American happy meal they might attain a family that has been broken apart and shattered all over the world. So the Swiss Miss is a red herring. The life-affirming “brekkie” (a Timothy Donnelly import) sings the tune of a pathetic heroic where so much hope is not staked upon people but on sausage with eggs from Pop’s Diner, for example.

Food is a metaphor of the man-eat-man world of Ilium, where you are sized up the way a hunter might size up a prey. In Dominus, the speaker is hungry most of the time, and we see the speaker escape it with the plump, “sweet clementines” or the “fish laced with emerald.” Food can also be sinister: the twinkie (which I mentioned earlier) as “a Key to our repressed psyche” is a symbol of a kind of deracination that leads to the question of “just who am I”? The self also appears as food in “Squirrel on an October Late Afternoon”; “the swell of my nipples, that yellow muck / of bacteria, the crust of my skin crispy, // my garment tied with rope girding / an equator of red.” Here, at the “height of my suffering” is the body under attack by the body itself, in conjunction with drugs that are ingested, and their aftereffects.

There is a movement both across the collection and within poems in thinking about food as a vehicle of thought. If you think of the first section, “When Ilium Burns,” as the act of consuming and digesting, the last section, “Plus Ultra,” would be a release. As Juan Mobili observes, there is a panning out concurrent with the maturation of the speaker. You see that between the “Hymn of My Fair Lady Boss,” where the speaker must shed the blood of the lady boss to prove her valor. By the last poem, the “life-affirming brekkie” is no longer about “chomp[ing] them down” with ruthlessness. What is left is instead a desire to repay “kindness with kindness.”

RD: Yes, the book’s structure of sections takes readers on a journey as the speaker changes. Regarding the structure of the poems themselves, you write in a dynamic variety of forms, some of which are strict. “A Twinkie’s Love Song,” for example, is a ballad in iambic tetrameter with a rhyme scheme, and “Metamorphosis as Cassandra is a rhyming sonnet with lines of ten-ish syllables. What’s your process for determining a poem’s form? Do the words come first, or does a form invite language?

TT: It depends. By that, I mean, forms in poems like “Sea Floor” start off with an image, such as that of the “Heineken and cigarettes the / hakuna matata of loss.” The speaker was devastated by that sight. From that sight, I built it up with the imagery of deflation. The form, which takes place in conjunction with the breakdown of language, draws heavily from Myung Mi Kim’s Underflag (Kelsey Street Press, 2008) and Penury (Omnidawn, 2009) in thinking of how the elements of speech can be repeated across, up-down, and diagonally. What results is a map of the “Sea Floor,” of what can be found by the speaker’s mind which “wanders to the sweet thread named surrender.”

Other poems take up a form that mirrors the briskness and breadth of the modern-day cityscape, like the kaleidoscopic quality you mentioned earlier. I actually created collages of the photographs I took through the seasons, of The Thinker, Alma Mater, Maria Goretti, the sun, the clouds, and the trees. Katie Marya says that “order is a performance” that “feels good because we can’t perform like that in our actual lives,” and I found that the modified quatrain form with the second and fourth line indented, after poems by Timothy Donnelly’s Chariot, helped me capture that sense of wanting to see the “sublime before the sea stirs.”

The origami frogs and the metallic flamingo generate this breadth and briskness that contrast, for instance, with the more austere poems in couplets like “Holy Saturday” where the crisis of the self in the perception of: “The clutter around me shows how the cockroach/ to be exterminated is me” defines how much can be said (in line length) and what can be said (as time is running out). I think I was interested in dressing down (as opposed to up), in contrast with the iconographic Holy Saturday or the idea of specializing in a specific field.

Sometimes, as poets do, I become obsessed over a combination of things. “A Twinkie’s Love Song” is essentially Twinkie meets the albatross in the Rime of the Ancient Mariner. I decided to run with it, and the ballad form is of course riveting, and gallops forward stridently, and so there the language is formal, and more playful in the sense that it draws from an eclectic mix of fables and histories to answer the question: Just “who am I, sheared of my golden mane?” Here, of course, food takes on the sinister quality, as a name for Asian-Americans who are yellow on the outside and white on the inside, having been fully assimilated into “American” society.

There is a limit, of course, to the information that poetry can contain. Sometimes the speaker’s excitement in going to Court overflows the poetic line and becomes prose, as in “Elegy to the Foolish and Undignified.” Poems that take a defined form are more time-consuming to write, but at the same time, poems without a defined form are harder to revise, in the sense that the form has to feel true to the emotion, diction, and direction that the poem is going. That’s why “Train” underwent several iterations and drafts before finding its final form.

RD: Though there is a limit to the information a poem can contain, your work illustrates that there is no limit to how much it can transmit in spite (or because) of the constraints created by the line and by form. How did you find poetry? What is next for you as a poet?

TT: I love that idea, because the formal constraint placed on language is often quite freeing and can create neoformalist poetry of great merit, even if at times poets like Aimé Césaire feel the need to topple that. He writes, in Return of the Native Land, that “you could say that I became a poet by renouncing poetry. Do you see what I mean? Poetry was for me the only way to break the stranglehold that accepted French form held on me.” This is in line with an Audre Lorde quotation: “The Master’s tools will never dismantle the Master’s house.” I feel that’s so true, and I suppose I often worry that my poetry isn’t too conformist.

Many English classes led me towards poetry—I read Paul Laurence Dunbar in middle school, Dante and Nabokov in high school, and so on—but I did not study poetry in earnest until my sophomore year in college. I took a class taught by Joseph Fasano called “The Crisis of the ‘I,’” which opened my eyes to just what stories poetry can tell. My favorite poem is Larry Levis’s “The Widening Spell of Leaves.” I admire how the poet looks at “that spell, that stillness,” through his encounter in a foreign country to reflect upon his personal history, political history, and the history of difference in the United States. Then there is the idea of the self as persona, as in Louise Glück’s The Wild Iris (Ecco, 1992).

I realized pretty quickly that I was happiest among poets. Though I was not as learned or as good as my peers, I enjoyed writing tremendously. In college, I was lucky enough to study with Deborah Paredez, Dorothea Lasky, and Alex Dimitrov, and they taught me how to think through form and the poetic voice, and how it’s okay to love the here and now through art. Through them, I was introduced to poets like Myung Mi Kim, Carolyn Forché, and Kenneth Koch, and they still shape my poems to this day. I am grateful for poetry and its blessings.

As with most things, to quote the wooden board at my workplace, “There is only one way to success—it’s called hard work.” The truly dazzling host Malvika Jolly recently asked me at a Powerhouse Arena event organized by India Lena González what my dream was, as I approach my thirties. I said something asinine like winning the lottery, but ultimately what I most want to accomplish as I grow from student to teacher and gain recognition for my creative output is to be there for others as my teachers have been there for me. While I’m not there yet, I am beginning to see the labor in editing as work that sharpens my appreciation for the beauty of life I am not privy to.

In terms of what’s next: I am working on a series of essays about being me and alive. These essays (“On Accent,” “The Sound of Rain,” etc.) helped me understand who I am, but also sent me down a spiral of “sad-and-sadder.” After all, it is pretty depressing to see myself as a diasporic writer who may never belong or be accepted by American society. Luckily, one of my best friends suggested that I incorporate humor into my essays, and I was able to do so by thinking through “the extraordinary” through the Netflix series Extraordinary Attorney Woo. In this new phase, I hope to better capture the uniqueness of the sounds of Queens as a borough and the multidimensionality of the immigrant community of Flushing in my new work.

Rain Taxi Online Edition Spring 2024 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2024