MAHMOUD DARWISH, EXILE’S POET

Critical Essays

edited by Hala Khamis Nassar and Najat Rahman

Olive Branch Press ($25)

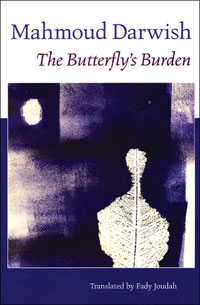

THE BUTTERFLY’S BURDEN

Mahmoud Darwish

translated by Fady Joudah

Copper Canyon Press ($20)

by Robert Milo Baldwin

Best known as the poet of Palestinian resistance, Mahmoud Darwish has a poetic range far wider than his politics. While resistance to Israel may be the engine for part of his work, the pain and isolation of exile is the fuel. In Mahmoud Darwish, Exile’s Poet, fourteen essays examine both his work and how an existential if not permanent exile is woven, if barely, with dangling threads of hope. As Darwish himself says, “be present in absence.”

Born in a village in Galilee in 1942, at age six Darwish fled with his family to Lebanon in the 1948 war, only to return a few months later to the new state of Israel to find his village gone. Growing up in Israel, he lived under the legal status of “absent-present alien” despite having been born there. For publishing and reading his poetry, he suffered house arrests and imprisonment, until his self-imposed exile to Egypt in 1970. From there he moved to Beirut, only to be expelled with the PLO in the 1982 Israeli invasion. Finally, after the Oslo Accords, he returned to Ramallah in 1996 to live in the occupied West Bank, where he later endured the 2002 siege of the PLO headquarters. As one essayist asserts:

What space can the poet claim after the loss of a supplanted homeland except the space of a poem? Poetry is the closest thing to granting a sense of belonging for the poetic voice that poses it as a question.

Darwish has written as he has lived, with the emotion of exile perhaps best described by Edward Said:

Exile is never the state of being satisfied, placid, or secure. Exile, in the words of Wallace Stevens, is “a mind of winter” in which the pathos of the summer and autumn as much as the potential of spring are nearby but unobtainable.

If we, as Americans, wonder why Hamas lobs rockets from Gaza into Israel, consider how we, as Americans, reacted to Arabs flying planes into the Twin Towers—we invaded two countries. If Darwish and others still long for their homeland, sixty years after losing it, why should we be surprised? The nearly powerless defiance of Palestinians is symbolized as much by young boys throwing rocks at tanks as it is by Darwish’s famous early poem, “Identity Card”:

Write down I am an Arab

You stole the groves of my forefathers,

And the land I used to till.

You left me nothing but these rocks.

And from them, I must wrest a loaf of bread,

For my eight children.

In the Arab world, poets are considered persons of vision and prophecy, feared not only by Israel but also corrupt Arab leaders. With only exile and no homeland, Darwish has often re-invented ancient myth, as if the reshaping of myth itself might become a new homeland, a “land made of words.” In so doing, he may astonish those in the West ignorant of how much common ground we share with the Arab world, such as Darwish’s allusions to Adam, Jericho, the Song of Songs, the Virgin Mary, and Jesus. As Darwish well knows, poetry sometimes allows a journey between different cultures and languages. By reshaping ancient stories, Darwish has attempted to form a bridge between cultures, so that a new version of an old story becomes “a counter-text, a kind of replacement of the original text by a new understanding, thus enabling the reader to confront the canon of the ‘other’ with a newly established or newly affirmed canon of his own.” Consider how Darwish retells the story of Adam and Eve:

Like Adam, the [poem’s] speaker even cedes a part of his body to make the creation of his female companion possible. The new Eve, Adam’s companion who is thus emerging and who receives her name through the poet’s creation act, is none other than Palestine.

This religious imagery has also been adopted by other Arab poets, some of whom draw a parallel between the crucifixion of Jesus and the injustice against Palestinians. If such imagery, for some, might quickly dissolve into anti-Semitism, Darwish asserts that the victims of the Holocaust do not have a monopoly on victimhood, and that the reshaping of myth is intended to remove us from the assumptions we’ve made about them and their “suffocating knowledge,” and to expand the dialogue among us all. For those who might question the intent of such a dialogue, it bears repeating that Darwish, as a young man, fell in love with a young Jewish woman—even though he later recognized such a love was “impossible to live,” and “located in sites impossible to inhabit.”

Where this leads, at times, is to the powerlessness of poetry, as if it has no value. Yet Darwish has never ceased to write, acknowledging that “the poet cannot but be a poet,” for he must “put himself in the wind and madness,” even if action is demanded over aesthetics. Yet the alienation of exile never leaves, as Darwish says so eloquently:

Perhaps like me you have no address

What’s the worth of a man

Without a homeland,

Without a flag,

Without an address?

What is the worth of such a man?

For Darwish, this no man’s land is one in which “I cannot enter and I cannot go out.” The bitter irony is that the refugees of the Holocaust resulted in the refugees of Palestine. This reality is often at the center of Darwish’s thinking; he rejected the Oslo Accords because it would lead to the apartheid of two separate states. Unlike Hamas, which seeks the destruction of Israel, Darwish apparently advocates “Israeli and Palestinian coexistence in a binational state with equal rights and secular citizenship.” In other words, he seeks the right of return to his homeland, with the full rights of a citizen to vote and otherwise participate in self-government.

Such political views often overshadow Darwish’s accomplishments as a poet. In The Butterfly’s Burden, translated by Fady Joudah (a Texas physician born of Palestinian refugees, and a member of “Doctors Without Borders”), the best poems are not so much about exile or oppression but the wonder of life, as in these lines from “Sonnet I”:

If you are the last of what god told me, be

the pronoun revealed to double the “I.” Blessedness is ours

now that almond trees have illuminated the footprints of passersby, here

on your banks, where above you grouse and doves flutter

In some poems, Darwish adopts the persona of a female narrator, as in “Housework,” saying, “A rain made me wet and filled with the scent of oranges.” In “Two Stranger Birds in our Feathers,” a woman asks a stranger to slowly undo her braids, saying:

Tell me some simple

talk . . . the talk a woman always desires

to be told. I don’t want the phrase

complete. Gesture is enough to scatter me in the rise

of butterflies between springheads and the sun. Tell me

I am necessary for you like sleep, and not like nature

filling up with water around you and me. And spread

over me an endless blue wing . . .

While poetry of politics and protest may wither past its time, the poetry of love can be timeless. What Darwish does is join the two together, as in “I Waited for No One”:

And go with the river from one fate

to another, the wind is ready to uproot you

from my moon, and the last words on my trees

are ready to fall on Trocadero square. And look

behind you to find the dream, go

to any east or west that exiles you more,

and keeps me one step farther from my bed

and from one of my sad skies. The end

is beginning’s sister, go and you’ll find what you left

here, waiting for you.

Perhaps Darwish’s poetry is best described by a line from “Maybe, Because Winter Is Late”: “a guitar that has opened its wound to the moon.”

Click here to purchase Mahmoud Darwish, Exile's Poet at your local independent bookstore

Click here to purchase The Butterfly's Burden at your local independent bookstore

Rain Taxi Online Edition, Summer 2008 | © Rain Taxi, Inc. 2008